When I visited the dark web for the first time some years ago — for a story I was working on, not to treat myself to some crack cocaine — I remember users constantly reassuring each other how truly anonymous it was. “The FBI does not have a prayer of a chance of finding out who is who,” was how someone put it in one of Bitcoin’s forums in June 2013.

A misconception, of course. While it’s true that the owners of Bitcoin addresses are supposed to be anonymous, the transactions are public for everyone to see. So once you know the person behind the address, illicit transactions can easily be traced back to the buyer or seller. Think of it as writing under a pseudonym; your privacy is protected until someone doxes you.

In some cases, this is as easy as doing a bit of Googling — more or less. Earlier this year, Qatari researchers crawled 1,500 hidden services, five billion tweets, and one million BitcoinTalk forum pages. They collected 88 unique Bitcoin addresses, and about 45,000 wallet IDs. In many cases, these online identities could be easily linked to real email addresses, social media accounts and sometimes even home addresses.

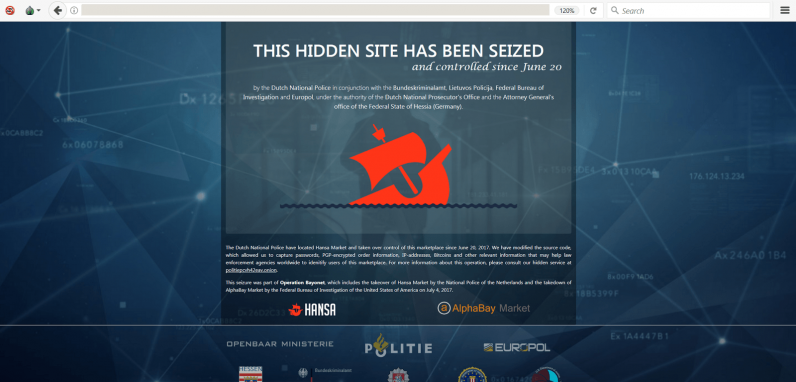

Taking over Hansa Market

When I ask police officer and dark web specialist Nan van de Coevering about this method to track criminals on the dark web, she bursts out laughing. “I wish it was that easy. Trust me, there’s a lot more to it than putting some nicknames in Google.”

Van de Coevering became head of the Dutch police’s dark web division in early 2017, about six months before her team would pull off one the biggest tech operations in the organization’s history: the takeover of dark web marketplace Hansa Market.

Back then, in June 2017, Hansa Market was one of the bigger marketplaces selling mostly illegal products. The police’s High Tech Crime Team had received a tip in 2016 that led them to the website’s server location, which was in Lithuania at the time of the take-over.

This was the game plan for “Operation Bayonet”: Programmers had built an exact copy of Hansa Market. They would take down the real version and immediately push their own copy live, so buyers and sellers wouldn’t notice anything was wrong. But because the website would be fully controlled by the police, they could monitor everything that went on from that moment onwards.

“We only had a few minutes of downtime,” remembers Van de Coevering. “But it felt like forever.”

The takeover operation took place in their headquarters in Driebergen, where we are meeting today. “We were all crammed in this tiny room: Nine programmers working frantically to get the website up as soon as possible, the rest of us there for support. It was one of the best nights of my career, but also one of the most nerve-wracking.”

Everything went according to plan. For 27 days, every transaction on Hansa Market was visible to Van de Coevering and her team. The website received about 1000 orders every day. “The international data was passed on to Europol,” says Van de Coevering. The data derived from Dutch trades on the platform, about 500 that month, were collected for further research.

The reason the Hansa Market operation focused mostly on the drug trade, as opposed to, say, child abuse imagery, was politically motivated to some extent, says Van de Coevering. “Drugs produced in the Netherlands have the dubious honor of being internationally recognized for their high quality and many suppliers are located here.”

“Catching the big guys — the vendors and admins — was our main priority,” says Van de Coevering. About a dozen of the site’s top drug dealers were arrested soon after the takeover, others are still under investigation. The police confiscated millions of dollars of bitcoin as well.

Buyers weren’t off the hook either. A few months after the infiltration, the police engaged in a “knock and talk” operation where they confronted 37 Dutch people with their drugs purchases on Hansa Market. One of them turned out to have ordered 150 ecstasy pills and was taken into custody, the rest was let off with a warning. “We want people to know they’re not anonymous on the dark web. We are there too and we see you.”

Linking personal identities to crypto transactions

So how did the Dutch police know on which doors to knock? Several methods are used to link personal identities to crypto transactions, says Van de Coevering. Like the Qatari researchers, her team crawls Open Source Intelligence (OSINT) sources to find matches. These sources can be social media profiles, internal criminal activity databases, public registers and even online newspaper articles, she says. “Once you have an electronic address, identifying a dark web criminal isn’t that different from traditional police work. It’s mostly digging and connecting dots.”

Regulated cryptocurrency exchanges — generally those in the US or Europe— can also be of service here. Because they are legally bound by “know your customer” policies and anti-money laundering rules, users can only register upon handing over identification.

How long it takes to find dark web criminals largely depends on how well they’ve covered their tracks. Often an escrow service is used, meaning transactions are not done directly but through an intermediary. Other times, buyers use a crypto tumbler (also known as a mixer).

This service obscures crypto payments by mixing them up with other payments. Or traders use software to convert “dirty” coins that are relatively easy to trace, like bitcoin, into more anonymous coins like Monero. Think of it as the crypto version of money laundering.

The Dark Web team frequently uses software by Chainalysis, a company that specializes in forensic analysis of virtual currencies. This program leverages machine learning to detect clusters of entities in the blockchain, some of which may be involved in criminal activities. When there are several addresses behind the same transaction, this could indicate one person is securing smaller funds into one bigger pot. Another suspicious pattern occurs when change from a bitcoin transaction is sent to a different account than where the payment originated from.

Ever-evolving crypto crime

In the past, Chainalysis’ software mainly focused its forensic work on one blockchain: the one that belongs to Bitcoin. When the company was founded in 2014, bitcoin was still an important coin of choice for dark web users. But crypto crime is rapidly changing and the share of bitcoin transactions sent to darknet markets has declined from 30 percent in 2012 to less than 1 percent in 2017.

“We have seen new kinds of crime popping up,” says Chainalysis CEO Michael Gronager. “Ransomware attacks, which have been more frequent over the past few years, often require payment in bitcoin.”

Gronager and his team are currently looking into adding new virtual currencies, probably starting with the bigger ones: Ethereum and LiteCoin. The more anonymous coins that are popular among criminals, like Monero and Zcash, might be added at some point but are not on the roadmap right now.

Which brings us to the more frustrating part of modern-day police work: There will always be new virtual coins to be used, new ways to hide illegal activities. Van de Coevering realizes she faces an uphill battle. “The dark web isn’t going away. Just like crypto crime will only become bigger.”

Operation Bayonet delivered a big blow to underground markets, specifically because it was coordinated with the takeover of an even bigger marketplace: AlphaBay. And the effect wasn’t just visible in those two marketplaces, researchers from Dutch research institute TNO discovered. They looked into Dream Market, where many AlphaBay and Hansa Market“refugees” migrated to after the takedowns. Data revealed that almost half of these vendors had failed to take evasive action like changing usernames or PGP setups. In other words, the takeover of Hansa Market seems to be a gift that keeps on giving.

Criminal communities are still thriving on the dark web, though. New markets have popped up, as well as new types of cybercrime. For the Dutch police, that means the organization needs to keep evolving and innovating. “We no longer just need good detectives,” says Van de Coevering. “We need people from various backgrounds: programmers, financial analysts, and cryptographers.”

Being self-taught, she’s a telling example of this new type of officer. “I still can’t write one line of code but I do fully understand how the blockchain works — a concept I had never heard about a few years ago. And if I can, so can you. All it takes is some time and a curious mind.”

Now that much crime has gone digital, the Dutch police need tech talent more than ever. Check out the various tech jobs they have to offer.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.