76.2% of abducted children who were murdered in the US were found dead within the first four hours.

It’s a terrifying statistic I recently learned listening to the podcast In the Dark, about the kidnapping and murder of 11-year old Jacob Wetterling in 1989.

In those first four hours, cars could have driven hundreds of miles, traces could have been erased, and bodies could have been buried.

It’s a no-brainer, of course: The sooner an investigation starts, the better the chances the perpetrator gets caught. This is true for missing person cases and for every other type of crime. And in a perfect world, the police would show up within minutes after every robbery or bike theft.

But we don’t live in a perfect world and police resources are limited. Which is why we need to tap into a mostly unused source to increase crime solving rates: the public.

Sharing police intelligence

Take missing person cases. Obviously, when a child gets abducted, the police takes immediate action, says Frank Smilda who’s the Head of the Intelligence Unit at the Dutch Police. But when it’s an adult who goes missing this can take up to 24 hours. Especially if there’s no reason to assume the person is in severe danger.

“Imagine someone you love goes missing,” Smilda tells me. “Even though chances are they will soon show up, those first hours are absolutely nerve-wracking. People who go through this experience tend to feel helpless and frustrated.”

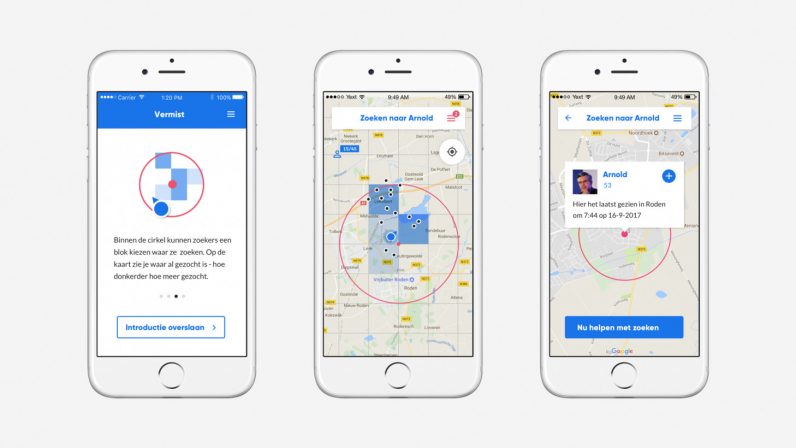

So why not offer them the tools to take action right away, help them navigate those first hours before the police starts investigating? This will soon be possible in the Netherlands, with the app SamenZoeken (“searching together.”)

“The radius in which we need to look first depends on many factors — whether the missing person is by car or on foot, whether they take medication, how old they are — which is common police knowledge,” Smilda says. “Through the app, we share that knowledge with the public.”

SamenZoeken, which is currently being tested and will be launched towards the end of this year, allows users to share their location and where they’ve already been searching, post pictures, and send direct messages to other users.

Online sleuths

Smilda is a vocal advocate for citizen investigation initiatives, which he believes can hugely increase the odds that crimes will be solved. He first realized this in light of the Deventer murder case, around 2005.

This notorious case of a wealthy widow being stabbed to death in 1999 is a pile-up of shaky evidence and unexpected twists and turns. The suspected killer, the woman’s financial advisor, was convicted — then acquitted — and then convicted and jailed again. His sentence ended in 2009, but he’s still contesting his conviction and poised to prove his innocence in court.

“This was one of the first cases in which citizen sleuths united online to effectively investigate every single detail and piece of evidence,” Smilda says. Now, more than ten years later, citizen investigations have become even more professional. “Just look at Bellingcat and their tremendous research work on the downing of flight MH17.”

Catching car thieves Pokémon Go-style

SamenZoeken isn’t the only citizen investigation app the Dutch Police is currently developing.

Another app, named Automon, follows a very different approach: gamification. Dubbed “Pokémon Go for car theft,” the app encourages Dutch citizens to spot stolen cars.

Here’s how that works: Public cameras (such as the ones in parking garages) will be able to recognize number plates of reported stolen cars. Whenever a stolen car passes by, app users in the area receive a notification with the number plate, color, and brand. Once they spot it and screen the number plate with their phone camera, they will receive some kind of reward.

“We hope to make a deal with insurance companies, which already offer financial rewards to private agencies that track down stolen cars,” Smilda continues. “Why not give that money to observant citizens as well?”

Although Smilda acknowledges the app will probably mobilize more users with money rewards, there’s more to the game than just hard cash. “Users will be able to design and build their own virtual car, for which you can earn new spare parts by spotting stolen number plates.” The plan is to launch Automon in 2019.

Sherlock, the last app in the pipeline, comes closest to ‘playing detective’: Users can create a virtual forensic file whenever a crime occurs. The app provides instructions on how to interview neighbors and write witness reports, shares insights on how to collect evidence, and even lets users create virtual composition drawings. Sherlock should only be used to investigate relatively minor crimes, Smilda warns — things like attempted burglaries, cyberbullying or vandalism.

Avoiding abuse

Letting citizens do police work — encouraging them even, by offering rewards— is not without risks. Going after suspected criminals could endanger the victims: What if they (accidentally) confront the perpetrator while conducting neighborhood research, who then responds with violence?

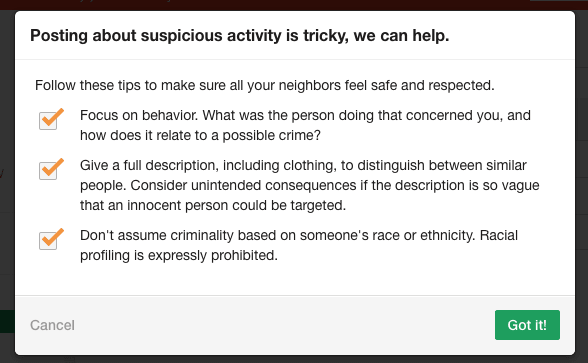

Moreover, it can amplify existing biases and result in racial profiling. Apps with similar ‘neighborhood watch’ features, such as market leader NextDoor, struggled with similar issues in the past years. The app had to be redesigned completely — making it extremely hard for users to include details about race in their reports — to drastically decrease racial profiling on the platform.

My mom forwarded me this racist message she got from her neighbor on something called nextdoor dot com. pic.twitter.com/Aih3DxsiwT

— Brunch Mocker (@mattcornell) April 29, 2015

Another crime-reporting app, named Vigilante, was removed from the Apple App Store in 2016 because of similar concerns. The app resurfaced in 2017 with a new name, Citizen. Though some changes had been made to address the issues, Citizen remains controversial.

Smilda understands these concerns. “Specifically with Sherlock, we have to tread very carefully to avoid abuse. This is why we are designing the app internally, while the other two were outsourced to tech companies.

Will he be willing to sacrifice the user experience in order to decrease ethnic profiling, like NextDoor did? “The app only exists as a mock-up right now, so it’s too soon to answer that question. But we will definitely take it into account when we start building the working prototype.”

What about amateur sleuths putting themselves at risk once they engage in vigilantism? This too can and will happen on a few occasions, Smilda admits.

But, he continues, what’s the alternative if you — let’s say — had someone breaking into your home recently? Sure you can call the police, but according to recent statistics, only 10 percent of burglaries are solved.

“It’s not that we don’t want to, but we have ten unsolved murders, twenty rape cases, and fifty armed robberies to deal with first. So the way I see it: We can just tell you ‘no, sorry, we can’t help you’ or ‘no, sorry, we can’t help you but here are some tools so you can help yourself.’”

Another solution to increase crime solving rates would be to just hire more police officers. Although that seems like an easy fix — assuming the Dutch government is willing to pay for it — it actually isn’t desirable, Smilda says. “We now have about 65,000 officers in the force. We could hire a few more people, but drastically increasing that number would turn the Netherlands into a police state. I don’t think that’s something we should wish for.”

As much crime has gone digital, the Dutch police now needs tech talent more than ever. Would you like to fight crime with code? Then find your future job here.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.