This article was originally published by on Cities Today, the leading news platform on urban mobility and innovation, reaching an international audience of city leaders. For the latest updates follow Cities Today on Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn, Instagram, and YouTube, or sign up for Cities Today News.

The actions of some big tech companies have led governments and the media to lead the accusations of big brother intrusion into our daily lives but Uber has put the boot on the other foot to lay into the Los Angeles Department of Transportation’s (LADOT) use of data. Over the past two years, the mobility company has fought to stop LADOT from collecting real-time data on its e-scooter and bike-share schemes, arguing that it infringes passengers’ privacy rights. Uber’s aversion to real-time data collection has spawned an ongoing legal saga that has been argued at the city, state, and federal levels with a script worthy of the world’s movie capital.

[Read: Proposition 22: Uber and Lyft’s last ditch attempt to keep their business model alive]

In an LA City Hall hearing in January, a lawyer representing Uber declared: “It is surely no exaggeration to say that what LADOT is proposing here resembles the world of a dystopian novel, like 1984 or Brave New World, where the government tracks its citizens in real-time about where people were, where they are, and where they are going.” While the Orwellian comparison has so far failed to convince the courts, the case has raised important questions about how cities use data and what limits companies are prepared to go to stop them.

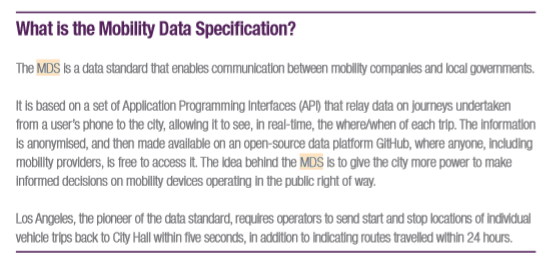

The dispute centers on the Mobility Data Specification (MDS), a data standard that facilitates the exchange of anonymized data between transport operators and municipal transport departments. It was first introduced in the autumn of 2018 but its origins can be found in LADOT’s 2016 transport technology strategy Urban Mobility in a Digital Age, which served as a roadmap for the city’s transportation future – encompassing everything from autonomous vehicles to mobility hubs. One section of the strategy, Data as a Service, spelled out how “the rapid exchange of real-time conditions and service information between customers, service providers, government and the supporting infrastructure” could optimize safety and efficiency, and improve the overall transportation experience.

The need for cities to have more control over the vast swathes of data generated by emerging mobility trends was something LADOT General Manager Seleta Reynolds had long been aware of. Prior to taking up her role in LA in 2014, Reynolds was head of the Liveable Streets division at The San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency, where she witnessed first-hand how ride-hailing companies had suddenly appeared and transform mobility in the city – not always for the better.

On arriving in LA, Reynolds was determined to take a more proactive approach and control the code as well as the road.

“We had been working on a series of studies trying to pinpoint how to undergo a digital transformation while taking into account the evolving roles private companies were playing in mobility,” says Reynolds. “It felt like we needed to architect a new model and a new way of doing this to communicate more effectively with businesses that were operating on the public right of way.”

In March 2018, Reynolds awarded a US$1 million contract for developing new standards for mobility operators to a relativity unknown tech consulting firm, Ellis & Associates, led by John Ellis — a former global technologist at Ford, whose work would form the foundations of the MDS. While initially created under the umbrella of managing multiple modes of new transport trends in a rapidly changing ecosystem, it was the sudden explosion of e-scooters on LA streets in the summer of 2018 which would serve as the catalyst for the introduction of the MDS in October that year.

To comply or not to comply?

Images of e-scooters being abandoned on pavements – blocking access for pedestrians, cyclists, and those with disabilities – became increasingly familiar throughout 2018, and firms like Lime, Spin and Bird faced growing scrutiny over their apparent failure to act. An increasing number of residents began to view the devices as a menace, and some even took matters into their own hands.

Videos and pictures of e-scooters being vandalized, set on fire and dumped in rivers flooded social media, and even spawned a dedicated Instagram page “Bird Graveyard” where disgruntled Los Angeles residents posted their handiwork. For Reynolds, the increasingly chaotic situation only strengthened the argument for the introduction of the MDS, which she felt would bring some order and accountability back to the streets. While the city’s micromobility operators had reservations about opening their data to LADOT, all fulfilled the new real-time data sharing requirements – with one notable exception. With a track record of taking a defiant and litigious approach towards city and state regulation, Reynolds says she was not surprised by Uber’s response to the MDS.

“The California Public Utilities Commission [which regulates ride-hailing in the state] previously had to fight to get data from Uber,” she explains. “They even took them to court to compel them to hand over data they had already agreed to submit.” Uber quickly began lobbying state legislators to support a bill that would restrict cities from gathering granular data on its Jump e-bikes and gained wider support from the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and the Electronic Frontier Foundation, who argued the MDS could leave personal data vulnerable to abuse.

“We’ve only had two government agencies ask us for this kind of information, one was LADOT – the other was Egypt’s intelligence service,” says Melanie Ensign, Uber’s Global Head of Security and Privacy, who has since left to become CEO of Discernible. Besides its privacy arguments, Uber also began to question LADOT’s relationship with the companies it collaborated with to create the MDS, claiming that the potential for the city or others to monetize the data being collected cast a shadow over the integrity of the program. LADOT hit back at the claims, taking the unprecedented step of publishing a set of privacy principles in March 2019 that stated it would never sell the data and would resist any requests from law enforcement agencies for access.

“You have to consider the key difference between the public and private sector,” says Reynolds. “We’re not doing this because we’re trying to turn a profit and grow the market; we’re doing this because we’re trying to keep society going.”

Growth of MDS

As the legal battle ensued, others were beginning to see the merits of introducing the MDS on their streets. By mid-2019, more than a dozen US cities had adopted LA’s data-sharing standard as part of their own micromobility schemes, and with the expansion, Reynolds saw an opportunity to create a network where cities, nonprofits, and companies could collaborate on its implementation globally.

In June 2019, she partnered with OASIS-a non-profit open-source platform-and 14 other cities to create the Open Mobility Foundation (OMF). With the City of Boston’s former Chief Information Officer Jascha Franklin-Hodge installed as Executive Director, the foundation invited companies including Bird, Spin, and Microsoft (but not Uber or Lyft) to join, along with non-profits such as The Rockefeller Foundation and Metrolab Network.

“A huge gap had existed for a long time in cities’ ability to keep up with changes in mobility and effectively serve in their role as regulators,” says Franklin-Hodge. “I was very intrigued by MDS when I first encountered it because it represented cities recognizing this gap and saying, ‘Well, wait for a second, maybe what we need is not to bury our heads in the sand but instead to create our own set of modern digital tools that allow us to function as regulators or stewards of public space’.”

Funded by contributions from the Rockefeller Foundation, the Knight Foundation, and dues paid by its commercial members, the OMF now has over 50 member cites in the US – including New York, Seattle, Portland, Washington DC – and dozens more abroad.

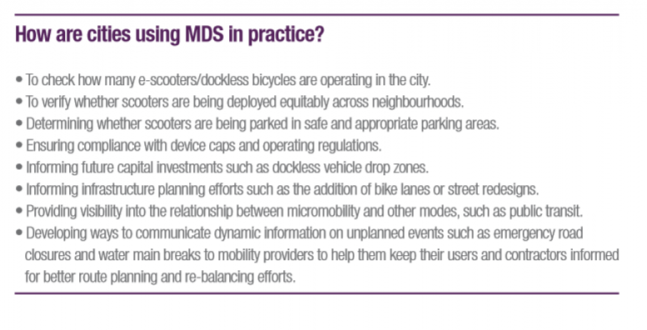

While the collection of real-time data is a key tenet of Los Angeles’ use of MDS, cities can take an a la carte approach to which elements of the program they want to use, with some, including Sacramento, Minneapolis, and Oakland, opting not to gather real-time data.

Commenting on the opposition Los Angeles has encountered, Franklin-Hodge says Uber is now facing a model of regulation it successfully avoided for its ride-hailing business. “In almost every single city in the United States where Uber launched, they came in without permission, they often went to court and sued the local jurisdiction, and lobbied very heavily and successfully at the state level to pre-empt the ability of local cities to regulate ride-hailing on their streets,” he says. “They are now seeing an alternate reality they don’t like, where cities, from day one, have the data they need to understand the impacts and benefits of new services, and are empowered to make smart regulatory decisions.”

This reality hit home in October 2019 when LADOT suspended Uber’s permit to operate its Jump e-scooters and bikes, citing their refusal to comply with the MDS. Uber then appealed (and lost) a subsequent hearing in early February. Two weeks later an anti-MDS campaign group Communities Against Rider Surveillance (CARS) appeared, proclaiming itself as a collective of “concerned citizens, privacy and civil liberties advocates, and transportation innovators committed to making streets safer and more manageable while protecting rider privacy.” Along with seven small NGO’s, Uber was a founding member.

Franklin-Hodge says the coalition is a “transparent astroturf campaign” by Uber, that makes inaccurate claims about MDS while ignoring their own legacy of poor privacy practices, multiple breaches of rider data, and falsifying information to regulators. Uber suffered a cyberattack in October 2016 that saw data from 57 million of its customers exposed, and did not admit the leak had even occurred until November 2017 – when it was revealed it had paid off the hackers with a US$100,000 ransom. A subsequent legal action taken by the US government led to a US$148 million payout, and Uber was also later fined by UK and Dutch regulators. In March 2017, the firm was found to have used a software tool called Greyball to actively deceive law enforcement officials in cities where its service violated regulations, using geolocation data, credit card information and social media accounts to identify individuals they suspected of working for city agencies tasked with investigating their compliance.

But on the MDS, Uber is not without supporters. It has found an ally in prominent US civil liberty group ACLU which has also raised concerns about the potential for MDS in Los Angeles to reveal sensitive data about users. While there is no evidence this has occurred, or to what degree it is likely to happen, it has cast a wider doubt over its use. Studies from MIT and the University of Texas have shown it is possible to reverse engineer the anonymisation of data, potentially exposing private information about riders.

Uber also seized on the Wall Street Journal’s revelation in February that the US Department of Homeland Security bought access to a commercial database that allowed it to monitor the movements of millions of smartphone users to track unlawful migrants. Reynolds concedes there will continue to be legitimate questions about how the government and cities manage the retention, protection and aggregation of data, but that there must be a balance in order for cities to be able to deliver quality services in an increasingly digitalized world.

“I don’t think this means we shouldn’t even collect data, to begin with,” she says. “This doesn’t just apply to the MDS; the government has been in the business of collecting sensitive information about people to deliver services for a very long time.”

Then came the climb down. In mid-March, as LADOT was reviewing six-month permit extensions for micromobility operators, Uber quietly informed the transport authority of its intention to comply with MDS requirements. “I was surprised,” says Reynolds. “After losing the appeal in February, the next step for them was to appeal that in front of the city transportation commission, but as we were preparing for that, we heard that they were no longer pursuing that hearing and intended to comply fully with all MDS requirements to receive the six-month extension.”

But while it had apparently complied, Uber added another twist. In late March it launched proceedings to sue LADOT in federal court, alleging its real-time data sharing requirements violated state and federal law, including the Fourth Amendment of the US Constitution. And last month, the ACLU also announced it had filed a lawsuit against LADOT and the City of Los Angeles over the same data requirements Uber has pushed back against, alleging they violate the Fourth Amendment of the US Constitution and the California Electronic Communications Privacy Act.

Uber maintains that it will not be adhering to the real-time data requirement, saying it only complied ‘under duress’ to gain the six-month extension.

“We reached an agreement with LA, in terms of latency, so that we could maintain our permit there,” explains Ensign. “But we still believe that their requirements are illegal under state and federal law. And that’s why we filed the lawsuit in March.”

“We have no plans to make similar agreements with any other cities – unless they want to be added to the lawsuit,” she explains.

One anomaly about Uber’s relationship with the MDS is that it contributes “quite a bit of code” to the open source platform on GitHub, according to Franklin-Hodge. “It’s a somewhat interesting dynamic that they are actively participating in the open source process, regularly attend our meetings, and are actually constructive contributors to the very thing their lobbying arm is trying to demonize.”

Ensign maintains Uber is not against MDS as a concept, saying standardization in the industry is a good thing.

“The whole point of the lawsuit is to seek guidance from the federal government on where the line should be. We don’t want to fight this battle with every single city in the world. But we need somebody other than lawyers in Los Angeles to confirm where the legal line is, so that we can apply that standard across the country.”

Looking to the future

As cities look for new strategies to manage data standards in mobility, more coalitions have emerged. In December, the Mobility Data Consortium (MDC) was launched by SAE International, a professional association for engineers, and in early May it unveiled two best practice guides to help cities with micromobility data management: one for data-sharing governance and contracting; and the other providing a glossary of terms and data metrics.

The group currently has 16 members, 12 from the private sector (including Uber) and four civic bodies – Tallahassee, Miami-Dade County, Bellevue, and the Denver Regional Council of Governments. Annie Chang, Head of New Mobility at SAE International, says the new consortium will complement, rather than compete with the OMF, focusing more on defining privacy standards than APIs and specifications.

She admits there is a “mix of feelings” among its members with regards to MDS, and that the organization plans to develop tools and legal clauses for authorities to adopt to address some of these concerns.

For Reynolds, the need for cities to have specific outcomes and clarity about why they are collecting the data is equally important. “The ultimate goal for us is to make the city transportation system work better, to give people more choices, and bring some order to chaos.”

But while cities struggle to control the chaos, the final act in this drama is most likely out of their hands. As Ensign says: “If the federal government tells us LADOT’s requirements are not illegal, then we can stop fighting.”

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.