Did you know we have an online event about the future of work coming up? Join the Future of Work track at TNW2020 to hear how successful companies are adapting to a new way of working.

Today, becoming a “startup nation” is a public policy objective in virtually every country in the world, be it Morocco, Bangladesh, Mexico, or Peru. They are all rushing to follow the nations that have led the way – the United States, China, South Korea, Israel, Canada.

France got off to a laborious start in the early 2000s, but has recently reactivated this goal. On October 10, 2018, President Emmanuel Macron addressed an audience of digital entrepreneurs at Station F, which calls itself the “biggest startup campus in the world,” and announced an ambitious roadmap to assist and promote entrepreneurs in France.

Everywhere, institutional pressure to transform young people into entrepreneurs is becoming an obsession. It’s a symptom, but of what? Can it not be seen as a sign of panic among politicians contemplating the shortage of prospects to offer young people?

[Read: How corporate layoffs could kickstart the next wave of startups]

A cascade of service providers

Let’s try to interpret this strange new command: “Become entrepreneurs!” It seems to suggest that established institutions only open up two avenues for the younger generation: opt for indigence with some degree of welfare assistance (e.g. a basic living stipend) or take a gamble. If so, then encouragement to create startups may be seen as the public face of a very discreet strategy on the part of large state and capitalistic organizations intent on sweeping this social issue under the carpet.

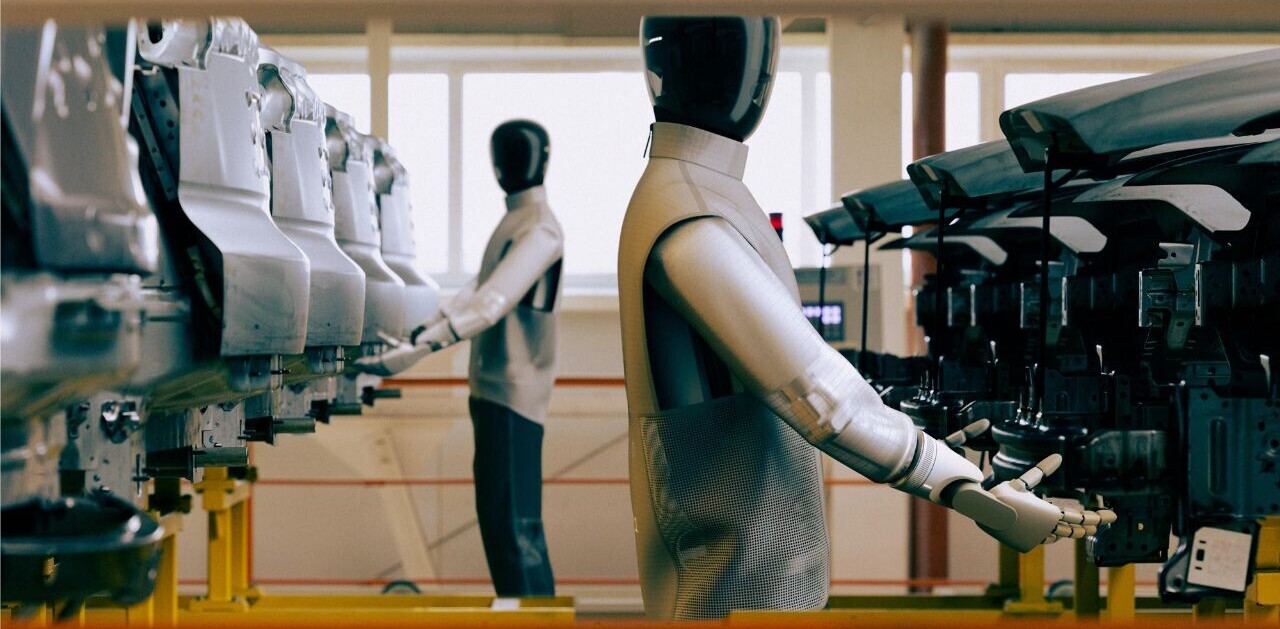

To an increasing extent, these same organizations are subcontracting, outsourcing, automating, robotizing, and digitizing to reduce the cost of labor as a percentage of total operating expenditure. They look for “talent,” i.e. a small minority of high-value added employees, while systematically avoiding the employment of workers deemed interchangeable, leaving them to the hard law of the market and progressively transforming them into service providers; into the providers of other providers; into the providers of providers of providers; and so forth.

A new wave of utopias

What’s going to happen to university graduates? Whether they major in physical education, humanities, communication, and journalism, marketing, or human resources, they all dream of finding jobs that will bring them self-fulfillment and even enjoyment. In France, they also expect five weeks of annual paid vacation and time off in lieu of overtime pay under the “RTT” scheme.

In the 1970s, young university-goers saw themselves as radical activists, reading Trotsky, Lenin, or Mao in preparation for the revolution to come. To a small degree, that dream has persisted in various forms such as eco-activism, alter-globalization, or feminism. However, it is now part of a new wave of utopias that amalgamates digitization, virtual reality, risk-taking, entrepreneurship, startups, easy money, the get-rich-quick ethic, and the cult of performance.

The problem is that, in today’s society, young people arrive in a job market that is not prepared to accommodate them. Leaving them to themselves, it calls them “entrepreneurs.” This magic word, with its connotations of freedom and hope, actually shifts responsibility for any eventual disappointments or failures onto them and them alone. Failure will then be a token of their inadequacy and the success of the few will be taken as proof that the many could have done the same, as Alain Ehernberg rightly pointed out in his book Weariness of the Self: Diagnosing the History of Depression in the Contemporary Age.

Even brilliant successes are problematic

In a previous article, I raised the issue of the rate at which startup founders meet with failure. I also stressed how little we know about the collateral damage to their lives and those of their families as well as, more generally, the social and financial cost of aggregate business closures.

It should also be noted that even the most brilliant successes are problematic. Inevitably, outsized ambitions to achieve impressive growth built from nothing or virtually nothing will have moral consequences on “les entrepreneurs et les entrepris,” a phrase coined by philosopher Héléne Verin, entrepris being a neologism for those caught up in the toils of entrepreneurship.

I encourage you to read an article on this subject by Diana Filippova, formerly the startup ecosystem lead at Microsoft France, in which she expresses her indignation at the Machiavellian behavior of some of the startup founders that have crossed her path.

In particular, she notes that young entrepreneurs, obsessed with growth targets and under pressure to deliver results, quickly become sharks. Some remain oblivious to the effects of their ambitions on those involved in or affected by their venture. Many careers starting out with the best of intentions end up marked by serial bankruptcies, business registrations, and cynicism.

Irresponsible opportunism

Startups like Cambridge Analytica or Theranos have displayed an extreme form of irresponsible opportunism. Was Mark Zuckerberg really so busy focusing on his own startup’s mega-success that he didn’t realize what he was doing prior to testifying before committees at the US Senate or the European Parliament committee hearing? Have Facebook users finally gotten the picture? Have they finally understood that Facebook, the platform enabling them to “stay connected with family and friends,” is also dirty, selling their personal data on the sly?

One lesson to be learned from the history of capitalism is that the accumulation of massive wealth in a very short lapse of time almost always involves predatory activities. To cite Aristotle’s terminology, this is chrematistikos (the art of acquiring wealth), not oikonomia (the art of running a household).

The investment funds that back startups exert pressure on them to accumulate as much wealth as possible as quickly as possible. And scenarios like this, in which outsized ambitions run rampant, are precisely those in which predation becomes the most probable factor of success.

Under pressure to succeed

Some successful startups, GAFAs, and unicorns achieve growth by crushing everything that stands in their way. But what about the entrepreneurs whose business, mismatched with the market, fails to get off the ground? This fragilized population is the one likely to suffer the most from the pernicious effects of propaganda in favor of entrepreneurship.

As Robert K. Merton pointed out in his book Social Theory and Social Structure (1968), “In societies such as our own, then, the great cultural emphasis on pecuniary success for all and a social structure which unduly limits practical recourse to approved means for many set up a tension toward innovative practices which depart from institutional norms.” He also noted that: “Several pieces of research have shown that specialized areas of vice and crime constitute a “normal” response to a situation where the cultural emphasis upon pecuniary success has been absorbed, but where there is little access to conventional and legitimate means for becoming successful.“

If the strongest survive, it’s often because they commit fouls on other players in the game, feel that “anything goes” in order to win and think that, on this playing field, the end justifies the means.

So, what are we looking at? Innovation or criminal deviance? Impressive growth or future disasters? New technologies that liberate or enslave? Social entrepreneurship or a well-planned, right-minded scam? Given its current modus operandi, entrepreneurship promises a fortune for the few, while the many slip and fall by the wayside. The moral climate of this “accident-prone” business environment can only be characterized as sinister.

This article was translated from the French original by Université Paris Saclay.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation by Michel Villette, Professeur de Sociologie, Chercheur au Centre Maurice Halbwachs ENS/EHESS/CNRS , professeur de sociologie, AgroParisTech – Université Paris-Saclay under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.