Microbes living beneath the seafloor feed largely on the products of radioactive decay, aided by sediment of the seafloor, a new study reveals. This finding radically changes how we look at life processes in one of the largest ecosystems on our planet. It could also alter our views of how life may have evolved on Mars or other alien worlds.

Typically, it was believed that organic material was the primary source of energy for microbes living far beneath the oceans. However, most organic matter is consumed on the seafloor, or just beneath it. Researchers were able to determine that radiolysis (the breakdown of water by radiation) is the principal source of energy for these aquatic beings in sediment more than a few million years old.

“This work provides an important new perspective on the availability of resources that subsurface microbial communities can use to sustain themselves. This is fundamental to understand life on Earth and to constrain the habitability of other planetary bodies, such as Mars,” explains Justine Sauvage, postdoctoral fellow at the University of Gothenburg who conducted the research as a doctoral student at the University of Rhode Island (URI).

[Read: How do you build a pet-friendly gadget? We asked experts and animal owners]

Your name is mud. Don’t worry — it’s a good thing

“Welcome to the new age, to the new age

Whoa-oh-oh-oh, oh… Whoa-oh-oh-oh

I’m radioactive, radioactive” — Radioactive, Imagine Dragons

Water molecules, as most people know, are composed of two atoms of hydrogen and one of oxygen. Nature, like middle school science students, can break water molecules into their component parts. They can also be split by naturally-occurring radiation, in a process called radiolysis, providing a source of energy for microbes.

This new study shows that sediment on the seafloor can raise the production of hydrogen and oxidants by up to 30 times compared to typical production in pure water.

“The marine sediment actually amplifies the production of these usable chemicals. If you have the same amount of irradiation in pure water and in wet sediment, you get a lot more hydrogen from wet sediment. The sediment makes the production of hydrogen much more effective,” Steven D’Hondt, professor of oceanography at URL explains.

Why marine sediment has this effect on radiolysis remains a question. However, D’Hondt speculates that minerals within the sediment may behave like a semiconductor, increasing production of the products of this molecular breakdown.

Waterworld is not as bad as you remember

“Radiolytic H2 has been identified as the primary electron donor (food) for microorganisms in continental aquifers kilometers below Earth’s surface. Radiolytic products may also be significant for sustaining life in subseafloor sediment and subsurface environments of other planets,” researchers describe in an article detailing the study, published in Nature Communications.

Our solar system — and galaxy — are replete with water worlds. This process might also take place on other planets and moons, providing an essential store of energy for alien microbes, researchers suggest.

The Perseverance rover which recently landed on Mars, has a primary mission of collecting samples on Mars to be returned by future missions. Once on Earth, those samples will be intensely studied by researchers around the globe.

“Some of the same minerals are present on Mars, and as long as you have those wet catalytic minerals, you’re going to have this process. If you can catalyze production of radiolytic chemicals at high rates in the wet Martian subsurface, you could potentially sustain life at the same levels that it’s sustained in marine sediment,” said D’Hondt.

In the video above, watch our interview with Steven D’Hondt on his work discovering a 100 million-year-old colony of marine organisms. (Video credit: The Cosmic Companion)

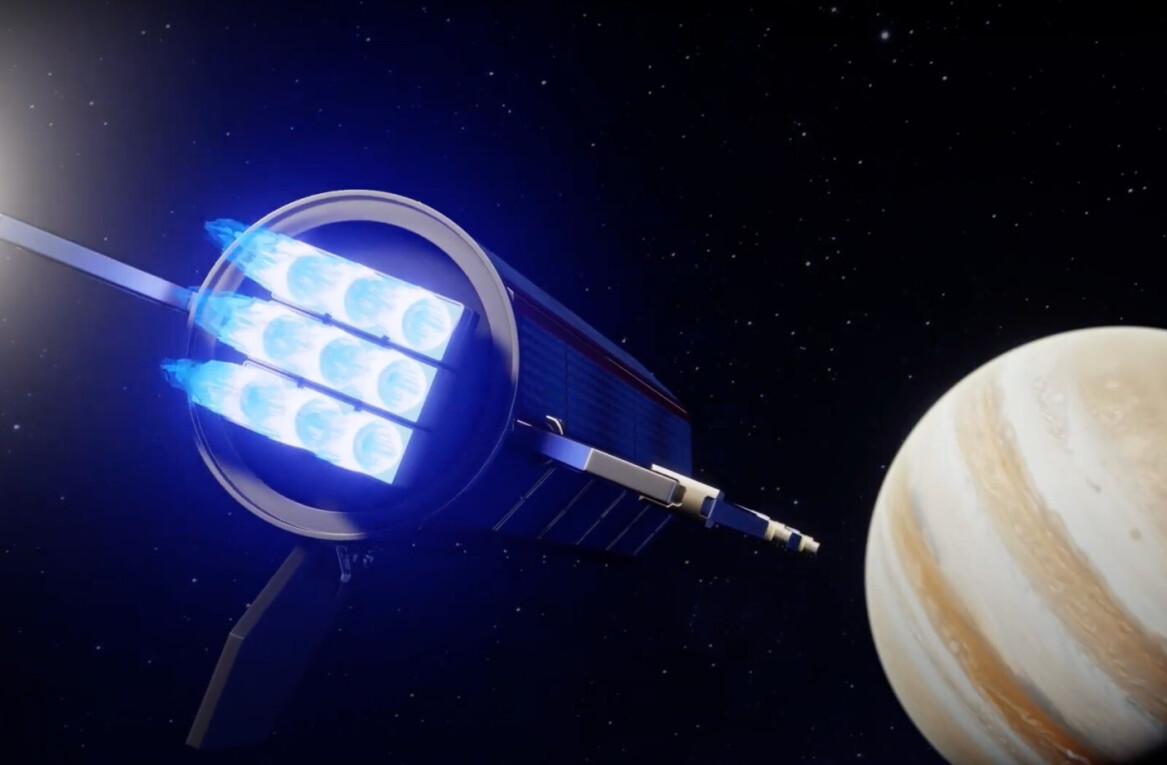

Europa — one of the largest moons of Jupiter holds far more water than Earth, making this Jovian moon an exciting stage to study how radiolysis might feed alien microbes on this alien world.

This finding could also have implications for nuclear waste disposal, and nuclear accidents, are handled. Nuclear waste stored in rock or sediment could generate hydrogen and oxidants at a significantly higher rate than the same deposits in pure water. These environments would be far more corrosive on storage systems than previously believed.

The team will continue to study how this process might behave on other planets, including Mars. Further examination of microbes will help the team better understand how microbes survive and behave when living off the products of the radioactive splitting of water.

This article was originally published on The Cosmic Companion by James Maynard, founder and publisher of The Cosmic Companion. He is a New England native turned desert rat in Tucson, where he lives with his lovely wife, Nicole, and Max the Cat. You can read this original piece here.

Astronomy News with The Cosmic Companion is also available as a weekly podcast, carried on all major podcast providers. Tune in every Tuesday for updates on the latest astronomy news, and interviews with astronomers and other researchers working to uncover the nature of the Universe.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.