As we set out on a two-hour drive, my pregnant girlfriend told me she didn’t want anyone, including ourselves, to share pictures of our child on social media. I was completely opposed, and we got into a heated argument.

The argument lasted most of the ride home. I didn’t understand the problem with other people seeing our undoubtedly beautiful child, our happiness, and their evolution into personhood.

I couldn’t fathom how we’d tell others to please not share pictures of our kid. I didn’t want to be ‘that type of person’; the type who eschews technology and forces others around them to bend to their will.

Most of all, I didn’t understand the problem with others creating their own stories around the pictures we chose to share.

My girlfriend didn’t back down though, and I am incredibly thankful she didn’t.

Who cares about your child?

The main reason I was so opposed, was because I thought her arguments were petty. Who cares what others think of how our child looks, how we raise it, and what they say about our little family?

But the more I thought about it, the more sense her arguments made. Not only because I try to be uninterested in what others think, but because of the platforms that stand between our family and the rest of the world.

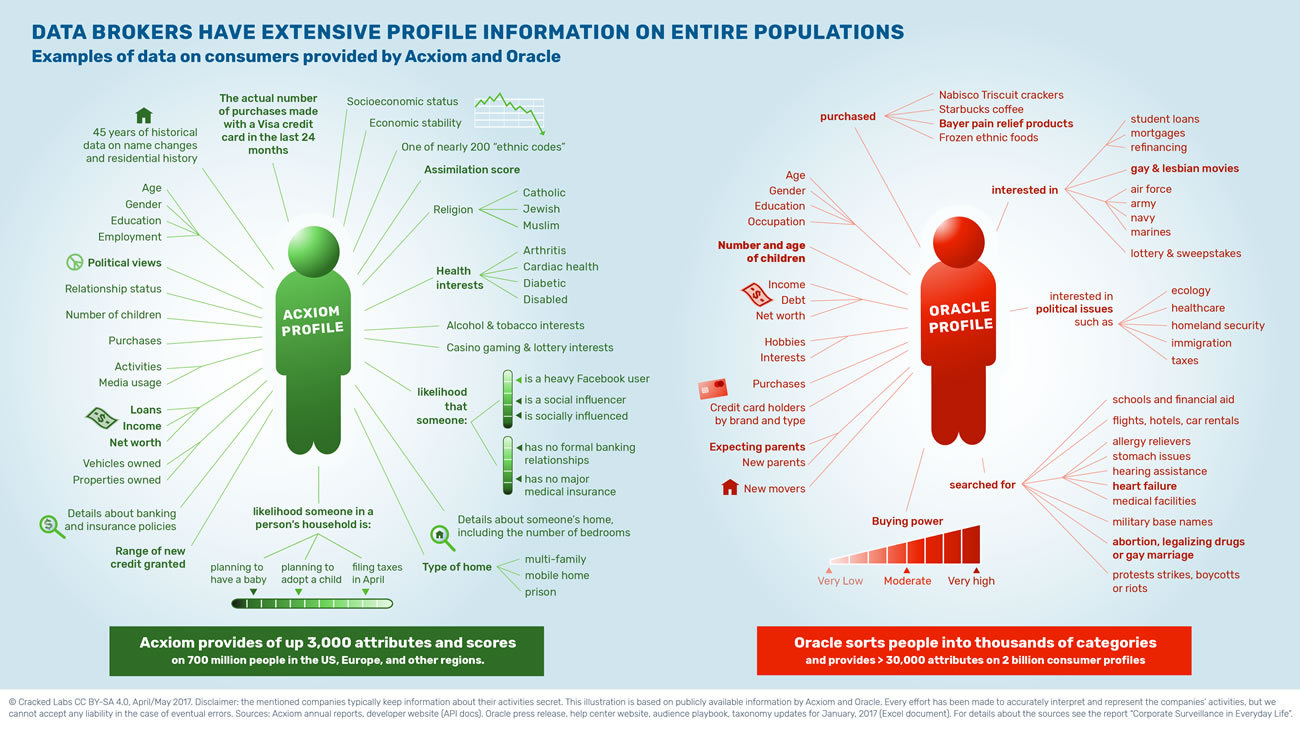

The thing is, it’s not only people who would form opinions, preconceptions, and narratives around our little human. It’s the Googles, Facebooks, Amazons, Epsilons, and all the thousands and thousands of data-collecting companies that create profiles around our online personas and the relationships we have with other people, things, and ideas.

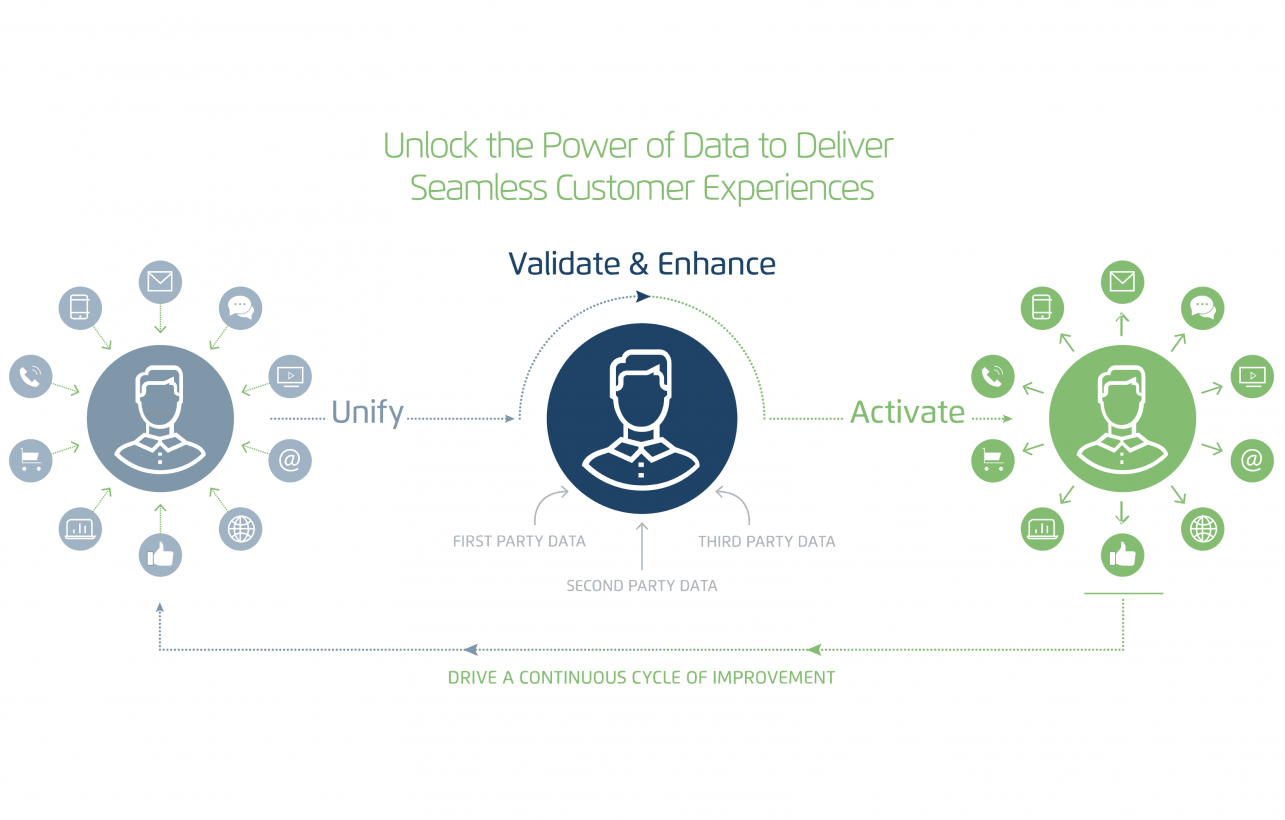

A cool (and terrifying!) marketing video by data broker Epsilon, watch and shiver in revulsion

It’s the online profiling of my currently unborn child – one that is probably already, unstoppably being developed from the baby sites we visit, the diapers we buy, the articles we read, and the other expecting parents we befriend – that I want to avoid most of all.

A report named Who knows what about me?, published this month by the UK’s Children’s Commissioner underlines this feeling. The report outlines “the collection and sharing of children’s data” and actually makes some pretty good points for current or future parents.

In the foreword, Children’s Commissioner Anne Longfield sets out hitting some brass tack stats: “by the age of 13, parents have posted 1300 photos and videos of their child to social media.”

According to the report they sourced, this is down from almost 300 pictures and videos in 2016, but nonetheless still a considerable number. What’s worse than that number, is the fact that people tend to share pictures on momentous occasions, inadvertently giving away personal information about their child.

Giving it all away

Sharing a picture on the child’s birthday, for example, tells advertisers when its birthday is. And if you forget to turn off location data, they’ll know where he or she lives.

If it’s a birthday party elsewhere, it can tell the advertiser what they like – i.e. dinosaurs in the Natural History Museum, or mummies, or royal offspring, or Disney.

And don’t forget “‘first day at school’ photos, which often unintentionally reveal the child’s location or identity through details such as school logos and street signs,” as the report states.

What many people (choose to) forget, is that sharing a picture on Instagram or any other service sets off a mechanism that slurps up the data contained in that in picture – who’s on it, where it is, what device it was taken on, the relationship of the people in it, and on, and on – slices it up, and shares it with whatever company finds that data useful.

Some of it might end up in the databases of the huge companies that compile commercially exploitable profiles of people. Some of it might be used to target the parents with ads for toys the child might be interested in. Some of it might be saved, lying dormant until it’s needed by an insurance company, or a bank, or to set bail.

This type of data, that is not directly given to social platforms, is labeled in the report as ‘given off’ or ‘inferred’ data. The data is not given explicitly, but extracted by companies like Facebook, Instagram (which belongs to Facebook), or Google from the innocent-seeming posts you might proudly share of your little cherub.

All of that is combined with other data already in the system to paint a digital picture of your child, which might not be completely accurate, but is still used by many companies to make decisions about them.

Everything you share “might have real, long-lasting implications on children’s lives,” the report states.

We’ll get to the cons of those real, long-lasting implications later, because not everything is terrible and there might even be some benefits to be had from selectively sharing data.

The good, briefly

Not all data are created equal. Pictures shared on Instagram are data, but so are anonymized health records. Data collectors are not all cut from the same cloth either.

In one example, local authorities in the UK collected data from children and parents to use predictive analytics to successfully flag children at risk of abuse to social workers, the Guardian reports. This could be seen as a ‘good’ use of data – if you can peek past the vaguely Orwellian veil.

But as with any other data collection, data collected for good can leave a record that might be at best hard to shake, and worst, completely abused.

The bad, extensively

The CCO report notes that they heard accounts of criminals collecting information shared by parents – date of birth, home address, and full name – that they used to apply for fraudulent loans and credit cards once the child turns 18.

Answers to common security questions like a mother’s maiden name, the name of first pets, schools, or cars are also increasingly easily gleaned from ‘sharenting’, as the report calls the tendency of some parents to share everything about their kids’ lives.

Now, the cases above might be extreme and rare, but what ‘legal’ entities like Facebook and Instagram can do might be even more concerning – because you can’t really report them to the police.

The CCO report details profiling of children based on shared data as a serious long-term risk:

Profiling is a process in which data about a person is analyzed using algorithms and machine learning “to analyze or predict aspects concerning that natural person’s performance at work, economic situation, health, personal preferences, interests, reliability, behavior, location or movements.”

It states these profiles can be used to determine preferences, predict behavior, and make decisions about individuals. In the most innocent case, this can be useful for advertisers to decide what products to show a kid (or their parent) and when – like around their birthday, the date of which you conveniently shared.

In more serious cases, profiling can be used to determine whether someone can apply for a mortgage, a certain health insurance, universities, or even bail. Something to consider next time you want to post something cute, smart, or silly your child did.

It all adds up

Profiles on individuals aggregate information from all kinds of different sources – sometimes starting even before the child is born – so everything you do, however innocent it might seem, just adds up.

To top it off, as slimy icing on a poop cake, some machines that do analyses on personal data (or any data) are, as the report calls it, “unfairly reductive,” meaning they don’t take kindly to nuances, excuses, or inconsistencies. A ‘bad behavior’ datapoint, like an unpaid bill, might flag you as unworthy of credit, even if you’re a model human otherwise.

And the rotten cherry on top is algorithmic bias, that creeps in because the datasets machines are trained on are skewed in one way or another, or because the human training it has certain conscious or unconscious biases. Bad example, but if the person training a college application algorithm hates really tall people because they always stand in the front at concerts, that might teach the machine to reject those applications.

There’s more!

I’ve only discussed what sharenting could mean for the future of a child, but there’s so much more, ranging from the aggregation of your child’s behavior online to the data collected by internet-connected toys and devices like baby monitors. The CCO report does a good job in detailing the risks of those, but for the sake of the lenght of this article, I’ll save those for future scary pieces.

Is there any hope?

The CCO report ends on some measures that are being taken, both legislative and educational, and some obvious and toothless recommendations to governments, companies, schools, and parents.

Also, regulation like the GDPR might give us more control over the data that’s being collected on us and our children, if it ends up being enforced. Just this month, Privacy International filed formal complaints under GDPR against a couple of the largest data aggregators over data protection infringements.

To give you an idea of scale, one of the accused is Acxiom, a data broker that boasts it has “multi-sourced insight into approximately 700 million consumers worldwide, and our data products contain over 5,000 data elements from hundreds of sources.” Those sources include social media, and one of those consumers might just be your (unborn) child.

So, nu?

As I’ll probably disappointedly notice when looking at the stats of this article, most people will be bored by the time they get to the third sentence, and won’t apply any of the nuanced suggestions above to keep the profile of their child as minimal as possible.

So I’ll boil it down to a simple way to ensure this. A way that brings us back to my persistent girlfriend and her stance on the matter, but also expands it beyond just pictures.

The easiest way to ensure a future in which your child doesn’t suffer consequences from your oversharing, is just don’t share.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.