Like most other companies, my tech- and design-startup has felt the impact of COVID-19. People taking more time with decisions. Growth is pretty much paused in some markets. Teams are working from home and creating new kinds of cultural habits in the textannotation”>organization.

We’ve grown from nothing to a company with customers in 130 countries in less than 12 months, and we hadn’t seen the coronavirus coming in any way — like most other startups. However, it’s become crystal clear to me that the way to handle a financial crisis like this is not just about remote work, cutting costs, and focusing as an owner, but also a whole lot about why, you do, what you do. What you want to change in the world. What you could name being an ‘author’ and not just an owner.

Let me explain what I mean by telling you a story…

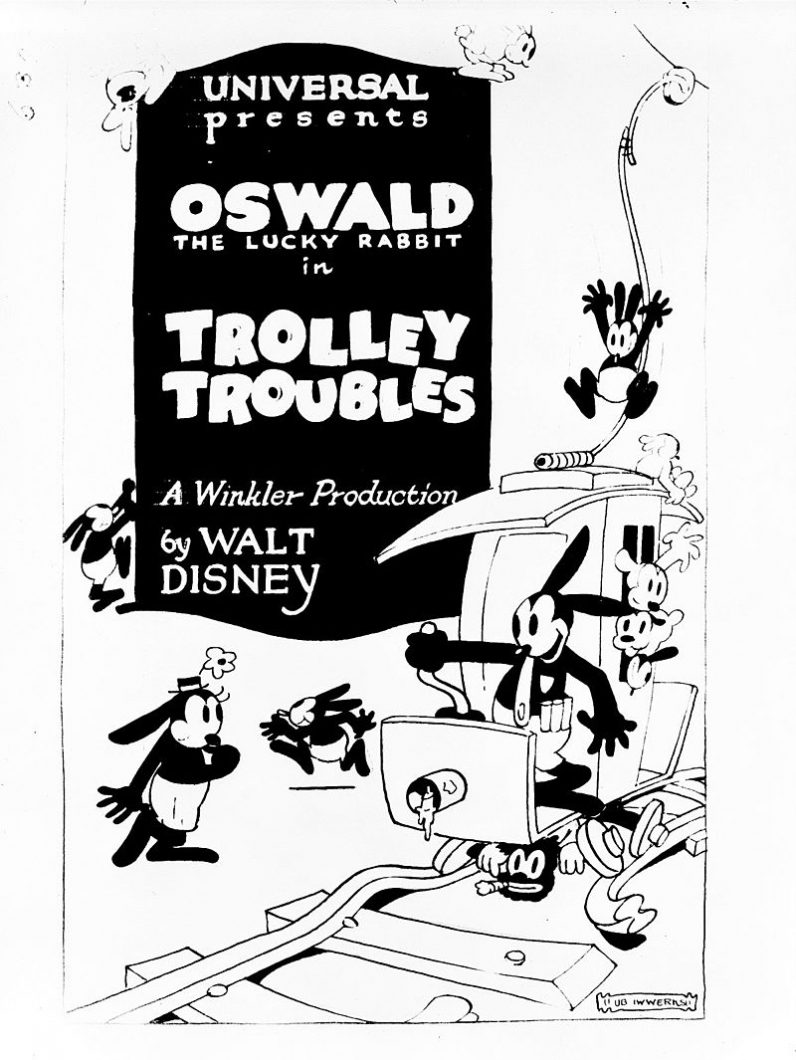

The story of Oswald the Lucky Rabbit

You might have never heard of Oswald The Lucky Rabbit, but in the late 1920’s he was more famous than Mickey Mouse.

Oswald’s story began when Walt Disney and Ubbe Iwerks — Disney’s star graphic artist — moved to California. Disney and Iwerks had made a name for themselves in Kansas making animated shorts, but when the cartoons proved to be less profitable than they expected, they decided to move west. In Tinseltown, the duo gave birth to Oswald, who became the new darling of the silver screen.

[Read: We asked 3 CEOs what tech trends will dominate post-COVID]

But Disney and Iwerks did not own their creation. Universal Studios owned Oswald, and its executives used this ownership to extort Disney after Oswald became a success. The executives threatened to poach Disney’s best animators if he did not cut down Oswald’s production costs.

Disney and Iwerks were deeply offended, but decided to avoid the legal battle — which they were likely to lose — and to focus on doing what authors do best. They created a new character in response to Oswald. That new character was Mickey Mouse.

Oswald’s story teaches us that what is most valuable in an economy is not what authors make, but their ability to make it. The executives at Universal tried to extort Disney and Iwerks by holding one of their creations hostage. But this was a naïve move.

While legally, Universal owned Oswald, technically they did not own the capacity to author characters like Oswald. That capacity was embodied in the minds of Disney and Iwerks, and this was the key factor that set the duo apart.

Understanding the perspectives of authors and owners is critical to understanding how authors and owners shape the economy. In the 1920s, it would have been easy to look at the success of Oswald and think that the character was where the value lay. But that interpretation, which is the owner’s perspective, is grossly mistaken because the real value was not in Oswald, but in the knowledge, artistry and creativity embodied in Disney and Iwerks.

As further proof of that, consider Disney and Iwerks’ next steps. After Mickey, they continued to push the boundaries of the film industry. Their next major project was a transcendental film: Snow White, the first full-length animated movie. At the time, the technology needed to create a full-length animated film was barely ready, and the project was considered ludicrous.

Nonetheless, Disney invested all of his wealth into the project, and when he fell short, he borrowed money to complete the movie by showing an incomplete version of it to lenders. Disney was willing to lose it all again to achieve his vision.

Actually, when you think about it, what Disney did back then was very much, what we talk about in today’s startup world and growth economy: risking going all-in, daring to fail. This is especially true now in a time of pandemic-induced crisis, where some may freeze because of fear rather than be daring like Disney.

The drivers of luminaries like Disney and Pixar

But the story of Disney and Iwerks is not an isolated example of the economic superiority of authoring vis-à-vis owning. A similar story can be found in the story of Pixar, where Ed Catmull, John Lasseter, and others pushed the vision of creating computer animated movies at great risk.

Making a computer-animated movie in the early 1990’s was as ludicrous as making a hand-drawn movie in the 1930s. But that ludicrousness did not stop Lasseter, who was unable to execute his vision at The Walt Disney Company and joined Ed Catmull in the startup that would later become Pixar. Together they triumphed with Toy Story, because among other things, they spent more than a decade developing the tools needed to author computer-animated films.

Ironically, they suffered a similar fate than Disney and Iwerks, since The Walt Disney Company owned the rights to the characters in Toy Story. But once again, authors prevailed by punching back with new creations. In this case: Monsters Inc. and Finding Nemo. Ultimately, the Walt Disney Company had to accept the creative superiority of Pixar, and decided to join them instead of fighting them.

But why would anyone want to be an author, and go through the stress, grief, and heartache required to make something at great risk? Simple monetary rewards are not the primary driver of luminaries like Disney, Iwerks, or Lasseter. Authors are looking to transcend, not because of ego, but because they want to contribute something useful, memorable, thought-provoking, or inspired back into the world that inspired them.

So while Universal executives saw Oswald as a way to make cash, Disney saw cash as a way to make history. Disney was authoring the history of animation, just like Lasseter would decades later. Being the richest guy in the cemetery was not what their work was about.

Owner and authors in the startup and growth-world

Certainly, there is a role for owners in the economy. Owners can help scale businesses and manage companies during the long periods of decay that follow the creative thrusts that originate firms. But the wealth of the wealthiest owners, the wealth of Carlos Slim, Warren Buffet, or George Soros, are pale accomplishments in comparison with the oeuvre of the greatest authors: the paintings of Picasso, the plays of Shakespeare, the induction laws of Faraday, the personal computer of Jobs and Wozniak, the cars of Ford and Benz, and the web of Tim Berners-Lee. For society, at least, it’s authors who create value.

At JumpStory we may be owners, but we also emphasize why our startup has put into the world all of the time — especially during the current COVID-19 crisis. Our team is not motivated by making money, but by transforming an entire industry — that of the image and video space.

When we grow, we grow, because we’re reinvented what it means to search for stock photography online. We’ve taken away the boring and cliche-looking images, and we’ve included diversity and authenticity into an otherwise boring and old-fashioned space. Find your own drive and make it clear to the world.

I truly believe that this is vital for growth-companies in the future. This ability not only to scale businesses as owners, but also to create something meaningful that lasts as authors. After all, those who really shape economies are those who change what economies make.

So you’re interested in growth? Then join our online event, TNW2020, where you’ll hear how the most successful founders kickstarted and grew their companies.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.