Liza Dixon, an autonomous vehicle researcher, hosted a TNW Answers session on Tuesday, 23rd June. Check out the questions here.

The first truly autonomous self-driving car will no doubt be one of the most historic technical achievements of our generation, but it seems we’re still a long way off because contemporary technology doesn’t yet fulfill the promise of keeping use safe 100% of the time. However, this isn’t stopping some automakers from talking as if we’re already there, and that behavior is creating new challenges.

Numerous automakers already present their driving tech as being capable of Full Self-Driving. The reality, however, is starkly different and more nuanced than the industry openly admits to.

[Read: What is CHAdeMO? Let us explain]

According to a new paper, published in the journal of Transportation Research late last month, this premature obsession with autonomous vehicles is having a detrimental impact on one of its main selling points: road safety.

Earlier this month, I caught up with the paper’s author, American born Germany-based, human-machine interaction researcher Liza Dixon. Dixon found her way into autonomous driving during her master’s in Usability Engineering. During our conversation, she told me what we need to know about autonowashing, the dangers of when vehicle manufacturers oversell their technology, and her research into the safe use of vehicle automation.

Where did it begin?

Dixon says it’s very difficult to say exactly where and when autonowashing began. Rather, the phenomenon is something that’s evolved alongside autonomous vehicle technology and narratives that surround the technology.

The concept of autonomous machines capable of sentient existence is nothing new. Science fiction writers have been exploring the moral conundrums and infinite potentials of them for over 40 years. In many of these fantastical scenarios, the results weren’t always positive.

Despite this fictional forewarning, companies that develop autonomous vehicles rely on selling a utopian vision of the future. One where technology can only do good. But that’s not always the case, and autonowashing is a perfect example of what happens when these narratives are bent and twisted out of shape.

What is autonowashing?

Autonowashing is similar to “greenwashing,” but applied to highly advanced vehicles, Dixon told me. In “greenwashing,” large corporations, typically those with a bad environmental reputation, undertake marketing campaigns to emphasize initiatives that promote more environmental awareness to make them seem more morally sound than they actually are. Here’s a good round up from not-for-profit, Truth in Advertising.

In autonowashing, vehicle makers manipulate what is actually very nuanced terminology to oversell the capability of their cars and make them appear more technologically advanced than they are. Tesla’s Autopilot and Full Self-Driving features in its electric cars, for example, are neither of these two things. Yet, because they’re brand names rather than literal descriptions, there seems to be little to stop Tesla from using them.

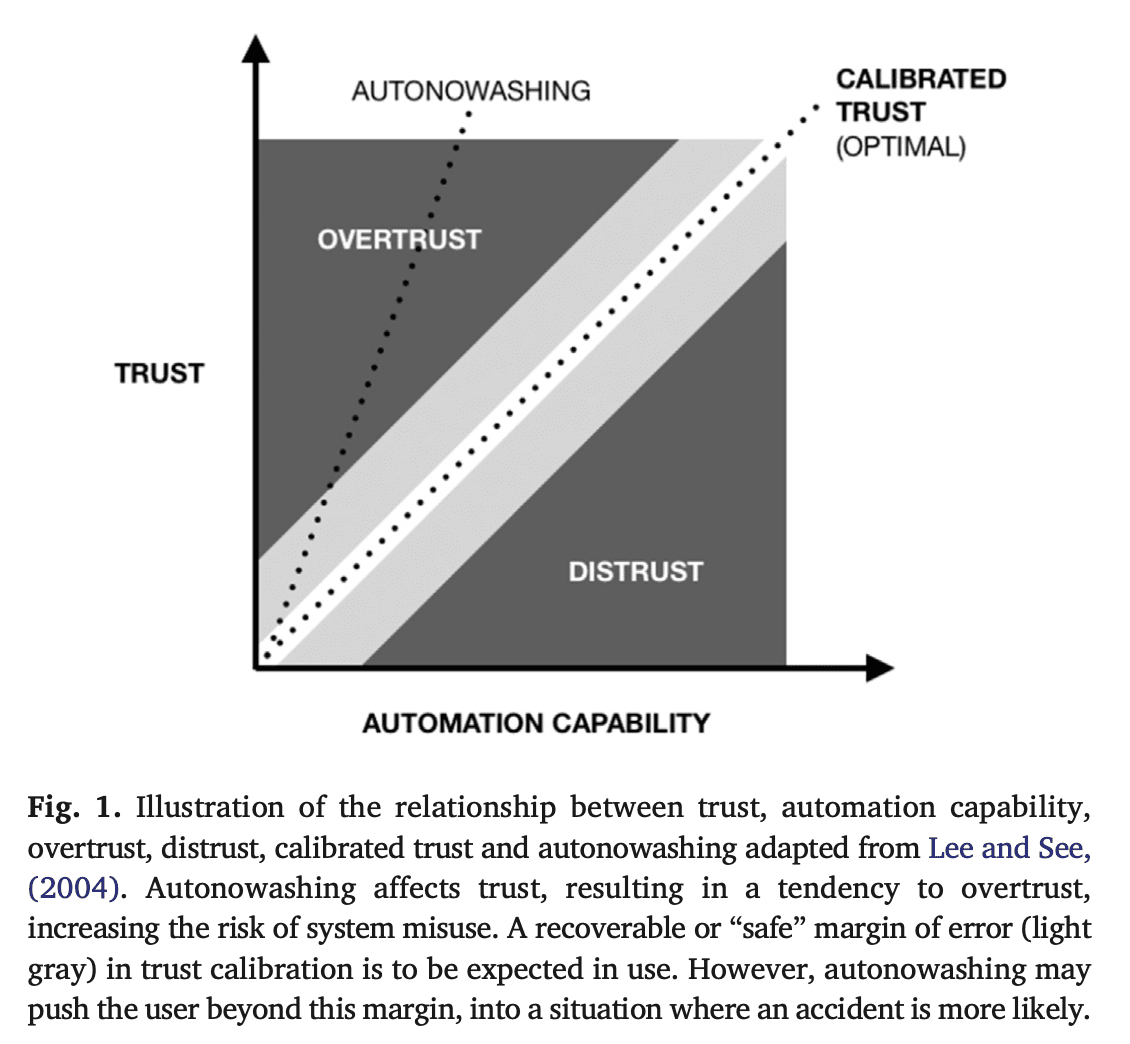

The Society of Automotive Engineers defined five nuanced levels of autonomy. Each level describes a subtly different manifestation of the technology. Level zero possess no autonomy whereas Level 5 is capable of true autonomous operation. However, as Dixon’s research shows, most in the consumer world don’t appreciate the subtle differences between each level and see all autonomous vehicles as one and the same.

[Read: The six levels of autonomous driving, explained as fast as possible]

“They’re not really designed to be consumer-facing. That’s not to say they’re so complex, the consumer could never understand them. The point is, they’re not made to be consumed at a glance. They’re something that you need to stare at and ponder,” Dixon said.

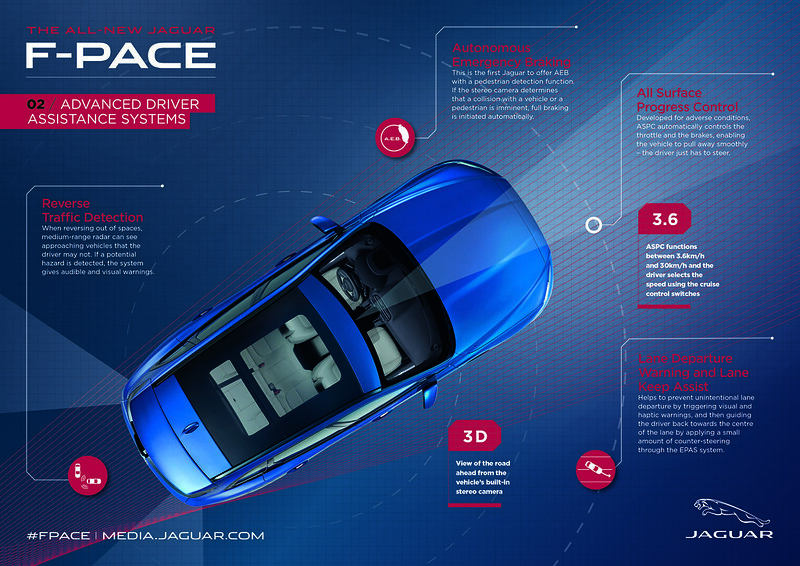

It’s important to note that Tesla’s systems are actually a group of Level 2 technologies known as Advanced Driver Assistance Systems (ADAS), but when all used simultaneously, allow the car to control itself in pretty much every way.

These technologies have been around for a long time and include everything from anti-lock brakes (first introduced in 1978 on the Mercedes-Benz S-Class) to adaptive cruise control and lane centering systems.

The SAE appears to be aware of how confusing ADAS terms can be, and has recently released an update to help clear up any confusion. However, all autonomous vehicles are still graded on its six-level system, even though, levels zero through two don’t possess any autonomy at all. It’s not necessarily the SAE’s responsibility to clarify these terms for the public, though. Dixon says manufacturers have a lot more to do to ensure their vehicles are used safely and appropriately.

Manufacturers need to wise up

Dixon’s research focus is on those developing, manufacturing, marketing, and selling the autonomous vehicle technologies. Tesla seems like an easy “fall guy” in this situation, as its Autopilot and Full Self-Driving systems are so well-known, but it’s far from being the only offender.

One of the most pivotal moments for consumer recognition of autonowashing came in 2016, following an advertising campaign from German automaker, Mercedes-Benz.

In an advertising campaign titled “The Future” Mercedes introduced an E-Class which it claimed could drive itself. The advert reads:

“Is the world truly ready for a vehicle that can drive itself? An autonomous-thinking automobile that protects those inside and outside. Ready or not, the future is here.”

Unfortunately, that campaign launched around the time that Tesla driver Joshua Brown died after his Model S crashed into a truck whilst Autopilot was engaged.

Consumers complained, saying the advert was intentionally misleading, and the US Federal Trade Commission (FTC) got involved. Mercedes initially fought the complaints, but in the end, the campaign was pulled. “Mercedes has been a lot more cautious and considered with its marketing since then,” Dixon added.

While Tesla isn’t the only manufacturer offering ADAS technologies, it’s a name that dominates when conversations discuss fatal traffic accidents where supposedly autonomous technologies were in use.

This might be because Tesla sells more Autopilot-equipped cars than other manufacturers do with competing systems. But it might also be selling more cars equipped with these systems because it oversells them. What Tesla presents is an incredibly sexy proposition. Fast, eco-friendly cars that can drive themselves — it’s understandable why people are so interested. However, to market them as such is misleading.

Back in 2014, the system was criticized heavily by industry experts saying its promise didn’t pair with its technology. For example, it cannot always identify small objects, or may see phantom vehicles which cause it to change speed suddenly. Years later, nothing has really changed, and the automaker continues selling features under misleading names like Full Self-Driving and the public is now accepting it, Dixon says.

Learn your levels

Due to how manufacturers talk about their vehicles, the mass-media and public has also adopted these terms. Which only further serves to perpetuate the confusion, unclear definitions, and overselling of the technology.

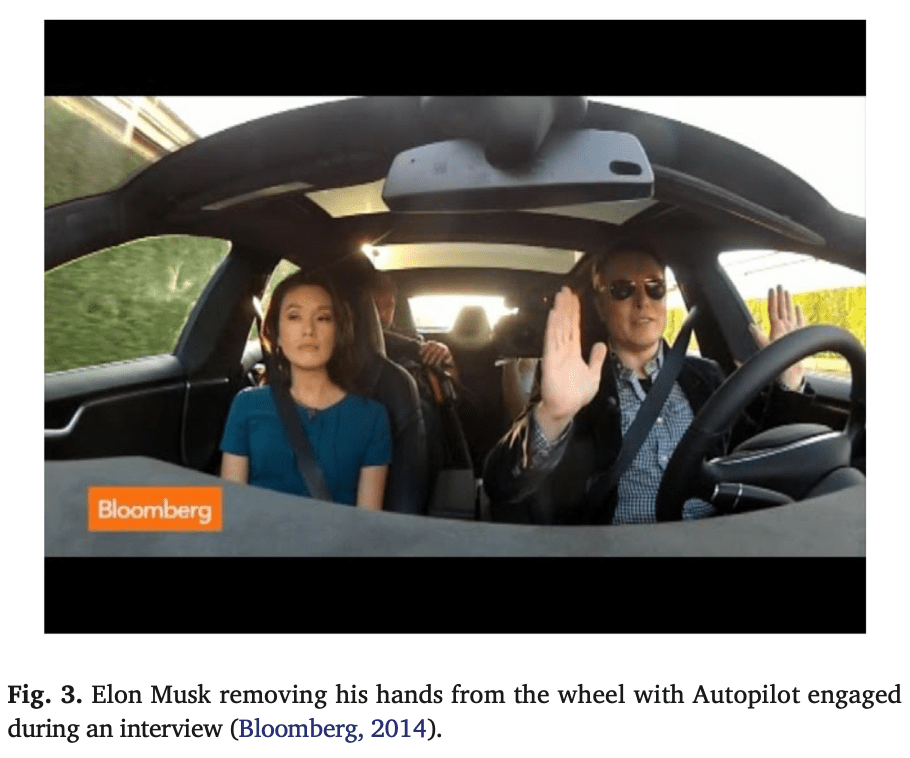

The end result is that drivers over trust their vehicle, drive without their hands on the steering wheel, and don’t pay full attention. Ultimately, they don’t truly understand the capabilities and limitations of their vehicle. Dixon calls this miscalibrated trust, but it doesn’t have to be this way.

Dixon says the ultimate goal for autonomous and ADAS equipped cars is to appropriately calibrate driver trust quickly and easily. Trust becomes miscalibrated when drivers don’t understand their vehicle but think that they do. This over trust is autonowashing, as shown below:

Moving forward in a positive direction

Dixon tells me, there’s plenty that can be done to address this phenomenon of autonowashing, and that it’s far from a lost cause.

It’s important to identify when autonowashing is occurring and take action. Dixon points out that many cases of autonowashing could actually be in contravention of Section 5 of the FTC Act, which is designed to protect consumers from “deceptive or misleading” advertising.

As it stands, there is also no standardized public terminology for discussing autonomous and high-level driver assistance systems. Every car brand calls its system whatever it wants, and describes them however they see fit. The SAE’s six levels are ones for engineers and carmakers, not the public, and have largely been co-opted and oversimplified.

Fixing this ambiguous terminology should be step one. Ultimately it boils down to manufacturers adopting common and clear language, Dixon says.

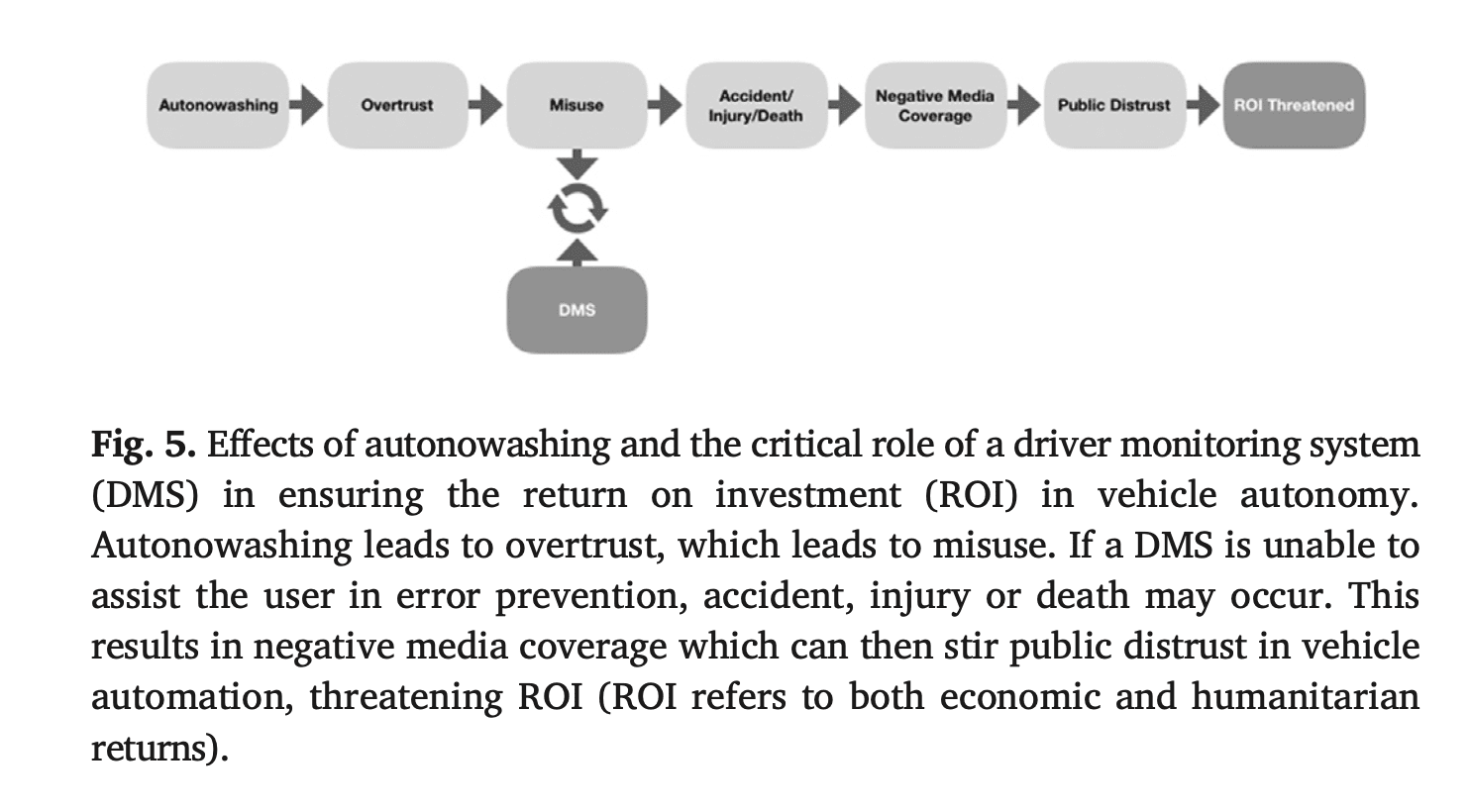

Another widespread issue, particularly with Level 2 ADAS equipped vehicles, that needs remedying is the absence of sufficient driver monitoring systems (DMS).

“The DMS is really the final step in calibrating trust,” Dixon said.

For example, Tesla uses a steering wheel-based torque sensor that only has the ability to sense when a driver applies or resists turns of the steering wheel. This isn’t foolproof, and it’s been “hacked” in the past and it’s been proven to be ineffective on long straight roads like highways where its misuse could be most lethal. What’s more, drivers fall asleep with their hands on the steering wheel all the time — a simple torque sensor is far from the most robust solution.

Manufacturers are aware they need to do more. After a string of Tesla Autopilot-related deaths, the National Transport Safety Board made a series of recommendations to all manufacturers to develop measures to prevent the misuse of “autonomous” driving technologies.

Five manufacturers replied promptly, saying they were working to implement the recommendations. Tesla, on the other hand, ignored the NTSB’s communications.

Perhaps the most important and most effective strategy is to educate drivers, so their trust is naturally calibrated, and they’ll drive safely. If this doesn’t happen, automakers will pay the price in the end.

Autonowashing leads to bad experiences. Eventually, customers will wise up and stop buying into oversold promises and stop buying those vehicles. Assuming they don’t take stronger action.

Earlier this year, TNW reported on a number of surveys which showed how the public doesn’t trust self-driving or autonomous vehicles.

Back in March, a survey from the American Automobile Association found that some 90% of Americans are dubious about self-driving cars. Another similar survey came to the same conclusion: American’s don’t understand or trust vehicle autonomy.

A study conducted by consumer insights firm JD Power which found that Americans don’t understand electric or autonomous vehicles. It seems this stems from a severe lack of awareness and education on the topics.

JD Power’s conclusion was very much in the same vein as Dixon’s warning to automakers: educate and safeguard your customers, or risk putting their lives in danger.

Perhaps someday, Teslas and other Level 2 vehicles will graduate to higher levels of automation, but we’re a long way away from that day. Until then, be conscious that what you’re being sold might sound sexier than it actually is.

If you want to read the full paper, click here.

Liza Dixon will also be hosting a TNW Answers session on June 23rd 1900 CEST, 1300 EDT, 1000 PDT, 2230 IST, where you can ask her your questions about the future of autonomous vehicles, autonowashing, and how humans interact with machines. Click here to take part.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.