Architecture occupies a unique place in the arts world. While it is typically a feature in movies, paintings, and games, it often goes unrecognized or unappreciated. I think this is because most of us have started taking the buildings we spend our time in for granted.

We go into our dull, grey, boxy offices and we leave at the end of the day, never once taking the time to notice our surroundings, or asking ourselves if whoever made this building had me in mind. Probably not; most buildings nowadays are built to be cheap, fast, and accessible.

But what if there was a new way of making you pay attention to the buildings around you; one that makes the architecture so bold and so invasive that we can’t help but notice it.

That is what Remedy has done with their latest game: Control.

“People ignore design that ignores people,” Frank Chimero said.

I am fascinated by buildings; they have permeated every aspect of my life and I’ve loved them for as long as I can remember. Be warned that if you and I are grabbing a drink together, you might lose my attention to the beautifully-crafted truss-system holding up the roof.

I can’t remember a time in my life where I didn’t have this obsession. I was always drawn to every clean line or interesting angle that framed a building’s form. Curved walls led to big reveals, and every door always hid a mystery. A natural love of architecture translated into a passion for movies as well. If you told me that a film’s setting is in a Modernist home or an International style pavilion, I was hooked.

This obsession, however, also led to some frustration. Why were none of my other friends appreciating architecture like I was? I’m reminded of a particularly painful sleepover in middle school where I can remember hearing that I would have to shut up or leave if I didn’t stop going on about how faithfully crafted the Art Deco world of the Bioshock series was. I wondered how so many people could play this game and not realize that the story was the architecture.

It struck me then that maybe the reason the architecture was still going unnoticed was that it still wasn’t real. While being based on an authentic architectural style, there wasn’t anyone out there building the next American version of Atlantis.

It would take a game where the architecture is real, something that anyone could experience anytime they wanted. We all, whether actively or passively, consider the buildings in our lives as living things. Remedy’s latest project was able to bring this feeling into my living room by making the Oldest House a character, and not just a setting.

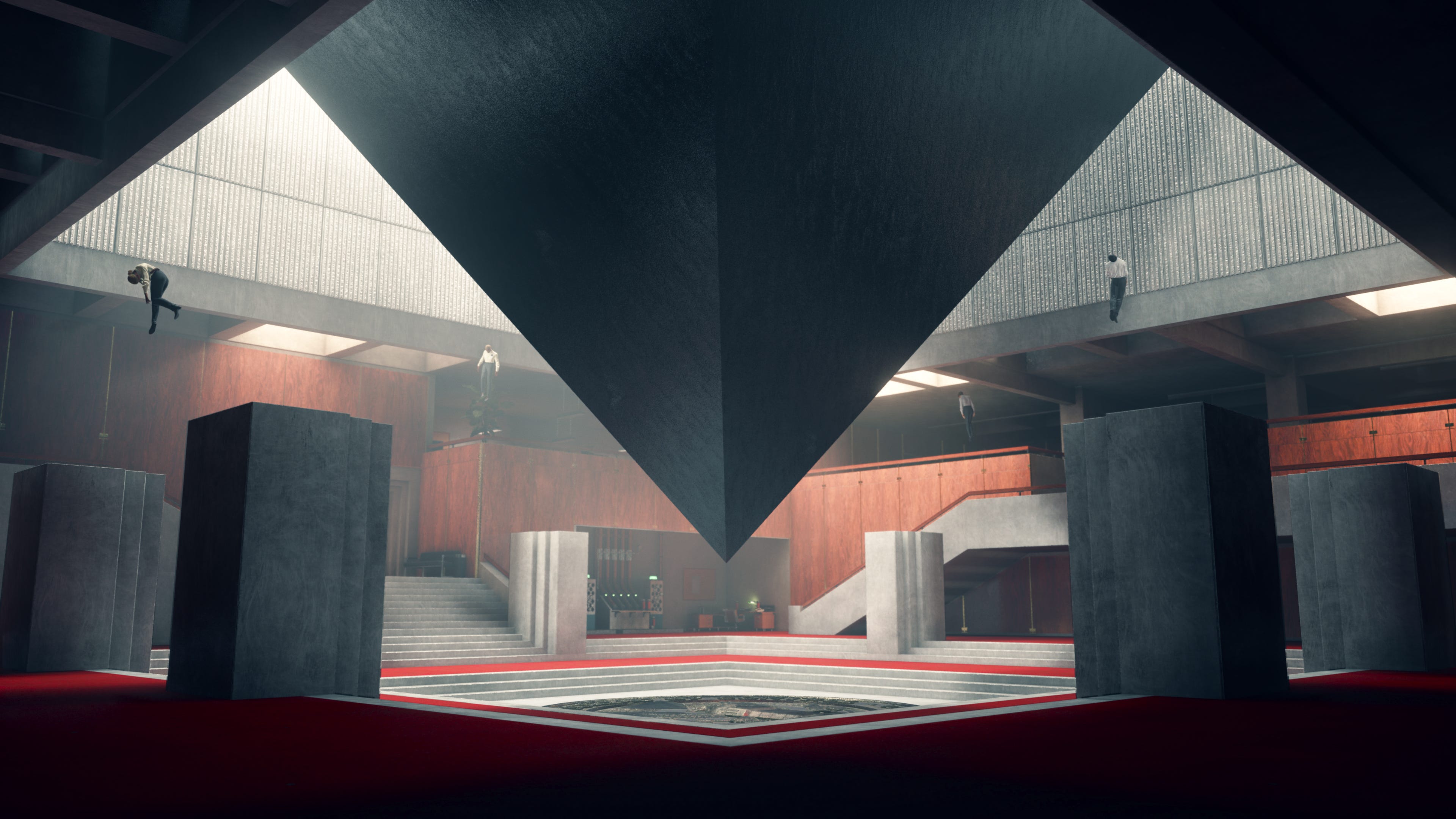

In a game where you play a pseudo-psychic government agent spending your time flying through the air and smashing your enemies under tons of concrete while defending the planet from an otherworldly invasion, you wouldn’t expect a big ugly box to take center stage.

Yet it does, and in an incredibly powerful way. But that’s the whole point of the Oldest House; it looms over you, it dominates you, it is always there whether you like it or not, just like the style it was fashioned after is intended to. The strong sense of enclosure that you feel in Control is based on many buildings that exist right under your nose.

Brutalist architecture, or Brutalism, is a polarizing style of design made up of bare materials, clean lines, and a feeling of power. I have never played a game where those features are so intricately placed and showcased in the game design. Control’s sparse use of color often highlights these notable elements. Everything is solid, flat, and bristling with texture. You can almost feel the rough, cold concrete surfaces around you — we’ve all been in places like this at some point in our lives.

To that end, there’s something familiar about The Oldest House. This might be due to the fact that every school you’ve ever been in (at least in America) has been designed to directly reflect the Brutalist style; in fact, most institutional buildings have been designed this way.

The intention is to make you feel safe and secure — or perhaps, in some circumstances, to make you feel contained or even controlled. Where are you supposed to go, after all, if thick, concrete walls surround you? There is a polarization at the heart of Brutalism — simplicity and freedom versus confinement and imprisonment. Love it or hate it, it’s there, and it will always be there. Or at least, that’s what the architects intended you to think and feel.

“An object should be judged by whether it has a form consistent with its use,” said Bruno Munari.

Admittedly, I find the style beautiful — but what if you hate it? Well, interestingly, Control gives you an architect’s dream game mechanic: destruction.

“Why don’t they just knock it down and start over?”

Everyone has said this at one point or another. Driving through town or walking down the sidewalk, you’ve inevitably seen a building that made you wonder why anyone would want to build it. Perhaps this is how you feel about Brutalism — but at least the style caught your attention, right? That’s one reason why Control is so brilliant. It forces you to engage with the world around you by appreciating its beauty or smashing it to bits.

I like ruins because what remains is not the total design, but the clarity of thought, the naked structure, the spirit of the thing,” Tadao Ando said.

Most architects will tell you that buildings tell a story through their construction. Control tells you its story through de-construction. We need more games like this — games that focus not only on architecture, but our intense personal relationship to the spaces around us, especially how we interact with them. Control echoes a walking simulator where you’re allowed to meander through your favorite museum — the difference, of course, is that here you can set your most hated pieces of art on fire, and I think that’s beautiful.

This article was written for SuperJump by Christian Waldo, an architect in the Seattle area.

SuperJump was founded by games journalist and product designer James Burns, and can be be found on Twitter and Facebook.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.