This article was originally published by Super Jump Magazine, an independent publication all about celebrating great video games and their creators through carefully-crafted, in-depth features produced by a diverse team of games journalists, designers, and enthusiasts.

The dust has settled — to some extent — on a major furore that swept the internet over recent months: the whole question of adding an easy mode to Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice. Some argued every game should be accessible to every player, while others pointed out titles like Sekiro are intended to be highly challenging, and it’s okay for some games to target specific audiences without the need to appeal to everyone at once.

But let’s take one step back and contextualize this discussion, at least in part, by pointing out that Sekiro is simply joining a long line of titles that prompted similar debates: games such as Dark Souls and Cuphead saw their own whirlwinds of controversy for broadly similar reasons.

What’s fascinating about these two factions is they’re actually both wrong when it comes to this discussion; perhaps to put it in less confrontational terms, I’d say they’re at least misunderstanding or misusing — without realizing it — the terms on which their arguments rest. Accessibility, for example, isn’t the right term to use when it comes to gameplay. Allow me to explain.

What does “accessible” mean?

Let’s start with first principles. My intention here isn’t to dismiss the importance of accessibility; it’s actually vitally important when considering video games — or any consumer industry — as it describes ways of enabling more people to experience something.

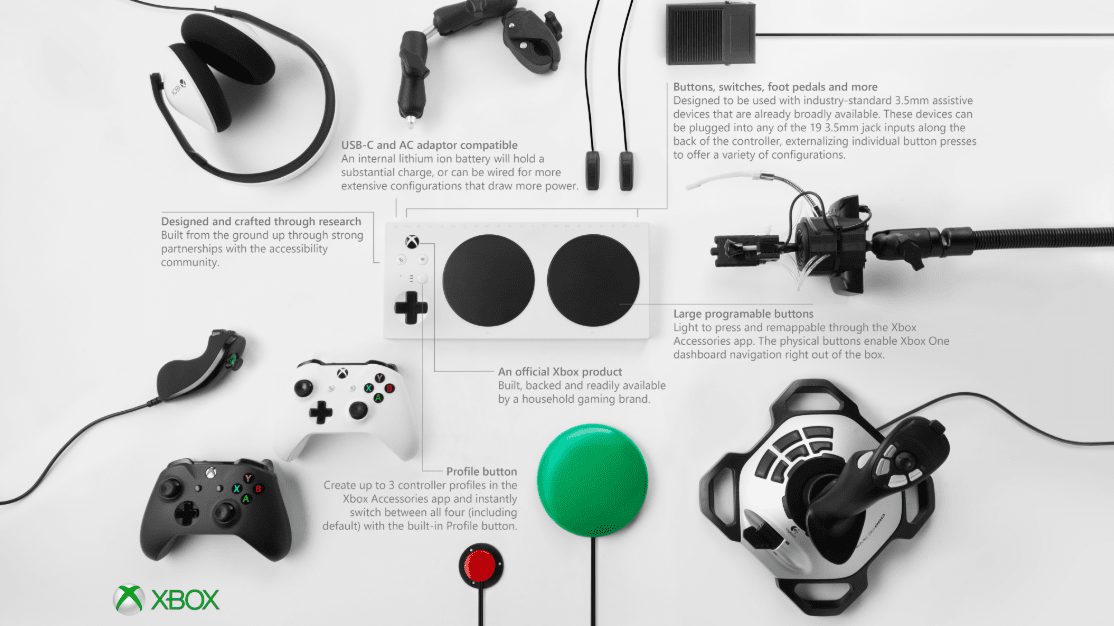

As an industry, video games continue to struggle with establishing standard accessibility features. These include — but are not limited to — subtitles (with appropriate display options), colorblind mode, support for accessible controllers, and a great deal more. The IGDA has a SIG (Special Interest Group) dedicated to raising awareness around making games accessible to people with disabilities.

It’s really unquestionably true where there are fewer barriers blocking players from playing a video game, everyone is better off. As an example, just this past holiday season, there was a great deal of discussion (and praise, rightly so) for Microsoft’s new Xbox Adaptive Controller, which was designed to enable people with disabilities to play video games.

So, let me be very clear: accessibility is never a bad thing. However, it’s not the correct term to use when talking about gameplay.

What does “playable” mean?

I’m going to use the term “playable” or “playability” here largely for lack of a better word — although I’ve heard some people use the term “approachability”. I’d define the term as being about how well a game allows players of different skill levels to experience the core gameplay loop.

Playability touches many different areas when it comes to game design. For example, an understanding of player psychology is important in terms of keeping a person invested in the experience. Knowledge of UI design matters when thinking about guiding players and giving them relevant information at the right time. There are many other disciplines involved in building a great video game. Fundamentally, though, if your game works well from a playability standpoint, then it’s likely a player who is either brand new — or an expert — can get something out of the experience.

By now, the fuzzy line between accessibility and playability might be coming into sharper focus. But let me draw a slightly sharper distinction: accessibility is about outside factors that outright prevent a person from playing your game, where playability is about the gameplay itself preventing people from experiencing it.

It’s for this reason the discussion around difficulty and accessibility doesn’t make sense, in my view. Difficulty isn’t a factor that can be accounted for by providing enhanced accessibility options (where said accessibility options are about enabling people with various disabilities to access the game). Based on the SIG link above, there are clearly-defined solutions and standards for helping people with disabilities through various accessibility options. But the same cannot be said about playability.

Now that I have established a clearer delineation between these two concepts, let’s return to the games I mentioned at the beginning and look at them through the playability lens specifically.

Cuphead doesn’t go far enough

There’s something slightly unassuming about Cuphead, at least if viewed without any knowledge of its development. On the surface, its gorgeous hand-dawn animation is a clear attention-grabber — but this cutesey paintwork hides a devilishly difficult run-and-gun style experience.

Right from the beginning, the developers were targeting classic gamers who grew up with extremely difficult games that rely on precision movement without putting a foot wrong. Interestingly, separate difficulty settings weren’t added until the end of development. Cuphead shipped with three settings: casual, normal, and expert (which is unlocked as part of new game+, after beating the game once). The difference settings affect the amount of health bosses have, how many phases the player has to fight through, and the overall difficulty of the phases themselves. When jumping from casual to expert, for example, bosses will throw more attacks at the player and will require greater hand-eye coordination to beat the challenge.

The playability issue here is that you simply can’t finish the game on casual difficulty; you must be playing on normal to fight the Devil/King Dice. This requirement — to play the game on the highest difficulty settings in order to experience all of the content — is something of a holdover from the old days, and feels out of place in a modern title.

Sekiro hits the wrong target

I’m not going to spend as much time on Sekiro, as I already discussed my issues with the dragonrot system in my piece on punishment systems in games.

The problem with Sekiro, from a playability point of view, is that its punishment systems are inherently weighted towards punishing new players. Unseen Aid and dragonrot only matter when you’re repeatedly failing to beat enemies. Once you know how to deal with each fight, those systems will never matter to you again.

As I said earlier, games with great playability can ideally. be experienced by players with a variety of skill levels — but Sekiro locks out a lot of novice players who may find themselves burned by the punishment systems. This problem is compounded because Sekiro provides few variations in terms of player tactics — there’s a specific way to defeat most enemies, requiring mastery of very specific techniques.

This stands in stark contrast to previous Soulsborne games.

If you play any of the Dark Souls titles, for example, you’ll find that you have different tactics available to you, especially if you get stuck. So, you might try a different weapon type, you might use spells at range, or you might summon a cooperative partner. You were free to play the game in a range of ways, enabling some flexibility in tactics, which you could change as much or as little as required.

In Sekiro, if you get stuck in any fight, you really have no other option aside from beating your head against the wall until you’ve either mastered a very specific tactic to defeat your enemy, or you’ve simply given up playing.

Celeste goes too far

Okay, here’s an odd one — why is a game that was celebrated for accessibility on a list of games that has issues with playability?

Celeste was designed around the idea of an “assist mode” that can be turned on at any time. Within the assist mode, players can switch on and off infinite jumping, remove any threat of failure, and can quite literally play through the game with zero challenge.

While that may sound like a good thing, I’d argue that this isn’t a case of designing a game around being playable — it’s more of a crutch. The game itself is fundamentally built on challenging platforming that expects a lot from the player.

What’s interesting here is that I found the levels themselves weren’t designed around subtly guiding players from point A to B via a clever design that is both playable for newcomers and possible to master for experts — something akin to Super Mario World. Rather, the game was built entirely around hardcore platforming — the assist mode is simply layered onto the design.

As a result, activating the assist mode is essentially the same as switching off the core gameplay loop itself. This makes me wonder if the core gameplay loop itself is as playable as it could be — if novices or less-skilled players need to switch it off, then what does this say about the merits of the underlying design?

Many people will argue that hard games are a sign of bad design in and of themselves. But I’d argue that the very same can be said of “easy” games. Playability might sit as a vital fulcrum between these two extremes.

Does “easy” make things worse?

Designing a gameplay loop that keeps everyone interested in playing is obviously much more difficult than it sounds. As I’ve explained, playability touches on so many areas of game design and I think this is partly why a lot of designers have trouble with it.

When considered in this context, multiple difficulty settings can be something of a shortcut to achieving a more playable experience. But it’s worth remembering that it’s very easy to simply ratchet up or down the difficulty to either extreme — it’s much tougher to design and build a thoroughly balanced experience. Given this, it’s no surprise that many games — regardless of whether they are indie or triple-A — only focus on difficulty settings, without the necessary emphasis on playability. This is my problem with games that have almost no challenge associated with them ( via the addition of an extremely easy difficulty setting)— if a person can experience your game without interacting with the core gameplay loop, then there’s a serious problem with your game.

I’ve lost count of the number of games that try to make do with an easy or casual mode, but still have fundamental problems with the structure of their design. A poor UI, lackluster tutorials — or, at worst, a core gameplay loop that simply isn’t fun to play.

One of the best examples of a game that hits the sweet spot in terms of playability, in my view, is Plants vs Zombies. This game features multiple modes and options for players of all skill levels to enjoy.

So how to summariZe this? I hope my argument has clarified what may seem like a very subtle distinction on the surface. The bottom line for developers, I think, is that if you rely on easy modes to make your game more widely playable — without examining how to improve the design of your core gameplay loops — then you aren’t learning how to improve as a developer. I realize there’s a great deal to unpack with that last sentence, but perhaps that’s a separate topic for another day.

Inaccessible, playable games

Ultimately, what does all this mean? Let me start by saying something that I hope should be uncontroversial: the best games are those that are designed around a specific market or audience. This means, by definition, they are going to be inaccessible to someone.

In this context, the goal of the developer is to figure out how they can make the experience playable for someone who has no prior experience with a similar design. This can sometimes be counter-intuitive, because many games succeed thanks to longterm, entrenched fanbases who come to any new game already knowing the fundamental rules of thumb — genres like grand strategy, visual novels, and 4X games are often not explicitly built around expanding their audience, as much as they are about guaranteeing a reasonable number of genre-literate players will buy these games with each new release.

However, there is always room to grow an audience — and while developers won’t (and shouldn’t try) to win over everyone, they can certainly increase their changes of expanding a game’s audience by emphasizing great playability.

SuperJump was founded by games journalist and product designer James Burns, and can be be found on Twitter and Facebook.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.