The EU has done a good job upholding net neutrality since it implemented a law on it back in 2016, but European net neutrality will face a new challenge in 2019: how to deal with 5G. The current net neutrality law is undergoing reform this year and it’s expected that it’ll largely revolve around the question of whether 5G should be treated like 4G and other internet services under net neutrality, or get special treatment.

5G is the much anticipated fifth generation of cellular mobile communications. It’ll be much faster than 4G (what most of us use to go online on our phones) and will require less energy, reduce latency, and increase system capacity and the number of connectable devices. 5G will allow you to view Instagram Stories faster and it could be great for driverless cars and IoT — but that won’t be clear until after 5G networks have been properly established.

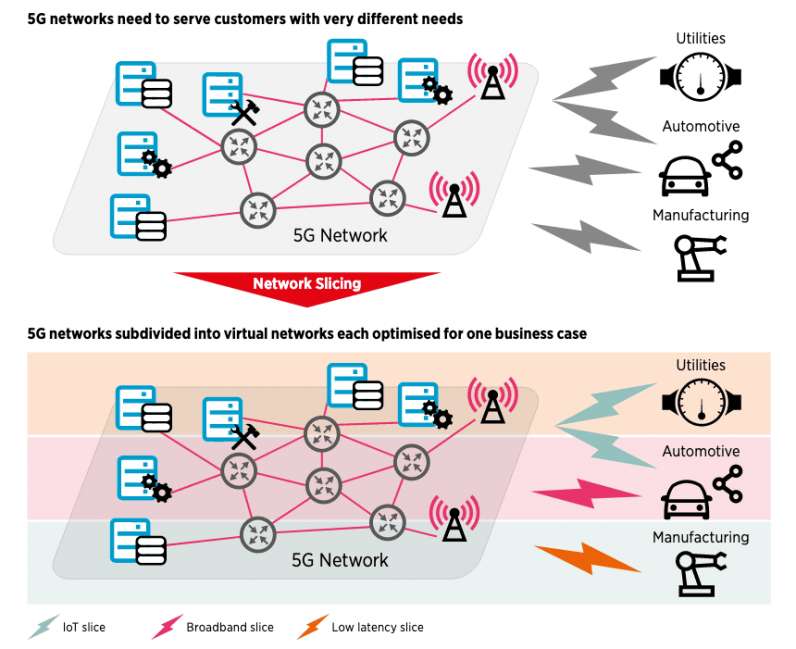

The reason why people are so optimistic about 5G’s role in emerging tech like the Internet of Things is something called ‘network slicing’ — the ability to segment radio waves into separate segments where each one has a different characteristic and separate from the rest.

So an autonomous car might use two slices, one high bandwidth slice for accessing general entertainment online — like watching Netflix on your way home from work — and an ultra reliable slice for telemetry and assisted driving — getting reliable information from other cars with near-time latency so you don’t crash into stuff.

Now, as you might remember, net neutrality is the principle that internet service providers (ISPs) should treat all traffic equally, preventing them from slowing down, blocking specific online content, or charging differently for specific uses. Basically net neutrality ensures user autonomy and prevents the segmentation of the internet, protecting its openness and global unity.

5G’s main quality enables actual ‘segmentation,’ which is why it’s being hotly debated whether it can be treated like previous generations of mobile communications by net neutrality laws.

What do telecoms want?

Telecoms are expected to argue for adjusting the net neutrality law and enforcement to fully utilize 5G’s network slicing, and charge separately for different segments, for example. Here’s how GSMA — representative of mobile operators worldwide and the association behind MWC — sees the business opportunities of network slicing (PDF):

“Just as digitisation has opened up the consumer market to a previously unimaginable array of experiences (most from outside the mobile ecosystem), we believe that slicing, and the adaption capabilities within, will be a similar catalyst for business customers, enabling them to facilitate their activities in ways we may struggle to even imagine today.”

Translating that to human speak: telecoms are extremely excited about the possibilities of network slicing as it would allow them to stop selling complete packages (or “one-size-fits-all sales models” as they like to call it) and instead sell more specialized packages — e.g. specify whether a customer gets ultra-high-bandwidth communication or extremely low latency. Telecoms argue this would benefit everyone and help with the adoption of 5G.

This view, however, isn’t shared by everyone.

5G shouldn’t get special treatment under net neutrality

“5G is an evolution, not a revolution,” Thomas Lohninger told TNW. Lohninger is the Executive Director of the digital rights NGO epicenter.works, which recently published a report on net neutrality in the EU (PDF). To him, it’s clear the existing net neutrality laws can perfectly accommodate 5G and shouldn’t be changed to appease the telecom industry.

“5G is a normal technical development. Our phones, CPU, and microchips get faster and faster every year because of innovation — and the same of course happens at the network level,” said Lohninger. “We knew this would occur because we’ve seen it happen over the past two decades. So in fact, there isn’t anything really novel about it — but it’s sold that way.”

To sell slices separately, 5G would likely need to be classified as ‘specialized services’ under EU law, which are exempt from net neutrality. Specialized services are basically “something other than the internet” and often use the same protocols or the same infrastructure as internet-connected devices, but are separate from the open internet, e.g. television or telephony voice over LTE.

“Specialized services is the biggest weak point we have right now. Weakening that would allow 5G to basically circumvent net neutrality completely,” says Lohninger. For him, it’s worrying that the ISP would act as a de facto gatekeeper, deciding which slice is most suitable for which application and charging accordingly. In extreme cases, it could result in users having to pay for each service they’d like to use.

“You don’t want to end up in a situation where Google could just pay to let Youtube become a specialized service — where you have existing online service being reclassified our specialized services — because that would mean you would have a paid fast lane that separates the big corporations from the rest of the internet.”

Lohninger is also skeptical about the projections telecoms have made for 5G business models and points out we don’t actually have an idea how novel 5G will be — so we shouldn’t compromise our net neutrality principles for network slicing.

“A big problem with the promises you hear on how great 5G will be and how much novel economic growth you can create is that it isn’t really based in a reality. It’s still really unclear what the killer application of 5G could be and how different it is to existing fast mobile internet connections. Of course it’s faster, but there’s no real difference besides the speed.”

The upcoming battle

To many it might seem innocuous to give 5G exemptions while the use for the technology is being established and infrastructure being created. Lohninger argues, however, that before we know it, 5G might become the standard for all our communication and browsing. That’s why it’s so important to adapt 5G to net neutrality, and not the other way around.

Lohninger says it isn’t unlikely for 5G to change how we use the internet and it could bring about new device categories — but that’s where the risk lies. He takes Apple’s push for DRM as an example, which greatly reduced device compatibility, that the company implemented when it launched a new device category, the iPod.

”This is something that would never have been accepted by the consumers on a normal computer, but was suddenly acceptable in this new category of device. So that shift in paradigm, might also allow to telecom industry to push for far more vertically integrated 5G-only devices,” explains Lohninger. Those 5G-only devices would then use the slices telecoms would dictate they could use, that’s why it’s so important to fight any reforms that might endanger net neutrality down the road.

Telecoms will most likely push EU regulators hard to convince them of treating 5G as specialized services during the review of EU’s net neutrality law, while NGOs and activists will argue against it — that’s the obvious part. But what’s not so obvious is how these arguments will be received.

European Parliament elections are coming up in May, which makes it harder to calculate how the reforms will go. Lohninger says the uncertainty of the Parliament’s composition can be viewed as a safety in the short term, but it does risk pushing the can down towards the national level — where telecoms might hold more sway.

“I can imagine national legislation could react to political pressure from the telecom industry — particularly because this will be in the same timeframe as the frequency auctions.” Lohninger fears that telecoms could use the cost of the frequency bids to push national governments to create 5G carve-outs in net neutrality enforcement or legislation to make it easier to recover the cost. He’s also concerned a possible fragmentation of laws on net neutrality which would undermine the level-playing field a Europe-wide legislation created.

That doesn’t mean there won’t be a battle on the European-level though. Regulators are already working on new draft on how to enforce net neutrality in regards to 5G. The draft will be opened up to public consultation later this year and set for implementation in March 2020. It’s going to be a busy year for net neutrality in Europe, the outcome of which could have broad reaching consequences.

Lohninger says there’s a lot to gain if the EU stands its ground on 5G — not just for Europe, but for net neutrality as a whole. He points out that South Korea seems to be weakening its stance and buying into the messaging of telecoms, so someone needs to step up quick and lead by example before more countries follow that route.

“If Europe shows 5G and net neutrality are completely compatible — and it’s for the economic benefit of everybody — then you would create a standard that others could follow,” Lohninger explains. He adds it would also be more likely the US could revive its net neutrality because showing 5G is compatible with it would avoid costly technical implementations and ease uncertainties about reinstating it.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.