This year cycling got its first British National Zwift e-racing champion, but it also got its first digital cheater. Last week, six months after wining, following a tip-off from an unnamed individual, the rider that won was stripped of their title and banned for “digital doping” – both from e-racing and real racing.

It’s not unheard-of for esports professionals to be banned from competition for cheating – and it’s certainly not unusual to read “cyclist” and “doping” in the same headline. But in this case we’re presented with the unique question of whether competitors should be banned in real life for something they did in a virtual tournament.

Wait, what’s e-racing?

There’s a lot to unpack here, so let me catch you up. Zwift is an online gamified bike training platform in which real-world riders race against each other in virtual reality. Think of it as one step towards a bicycle-based singularity.

To participate in Zwift you need a few things, a bike, a “smart trainer” which you attach your bike to, a paid subscription to Zwift, and a device capable of running it. (It can be run on desktop, iOS, or Android).

Typically, Zwift is used by hardcore amateurs to train in a virtual world on rainy days, but pro riders are also using it to train for real-world races – leading to unexpected wins.

One of Zwift’s biggest criticisms, though, is how it can be hacked, in some cases quite easily. This is a big problem as Zwift has ambitions to become an Olympic sport by 2028, it will have to address digital doping if this is to become a reality. For example, by under-reporting your weight you can gain a power to weight ratio improvement with no effort or you can use “bots” to increase your power or ride for you. Fitness tech guru DC Rainmaker did an excellent write up on the topic, read it here.

All things considered, this case probably shouldn’t come as all that surprising, but what actually happened?

Cycling’s “digital doper”

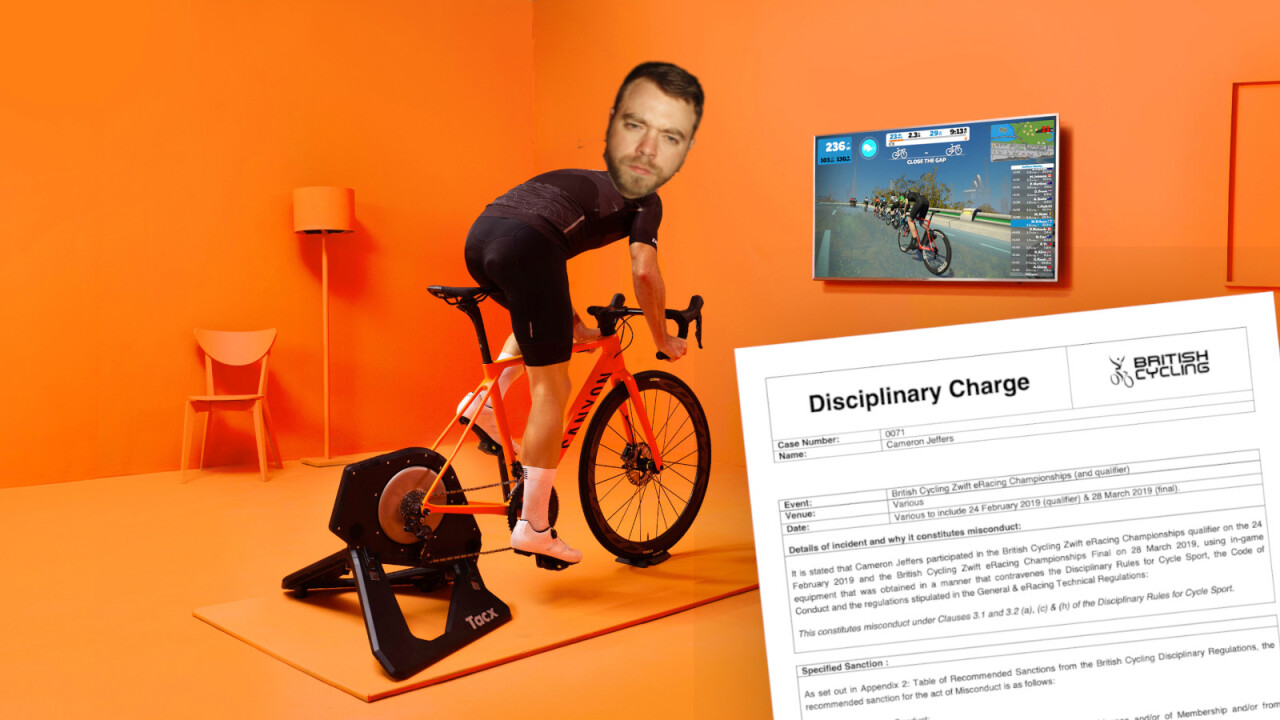

Back in March, British professional road racer and YouTuber Cameron Jeffers won the inaugural Zwift eRacing championships. And this wasn’t just streamed from some guy’s basement — the competition was officially sanctioned by British Cycling and televised on British TV. The riders had to complete qualifying rounds, the competitors were full-time athletes, and the title of ‘British eRacing Champion’ is truly legitimate.

It all came down to this, watts, watts, and more watts! ??? The 2019 Men's @BritishCycling Zwift eRacing Champion is @Cameron_Jeffers. #BCZwiftChamps ??

Official results:

? @Cameron_Jeffers

? James Phillips

? @MosesTom pic.twitter.com/bjKU0yX8n8— Zwift (@GoZwift) March 28, 2019

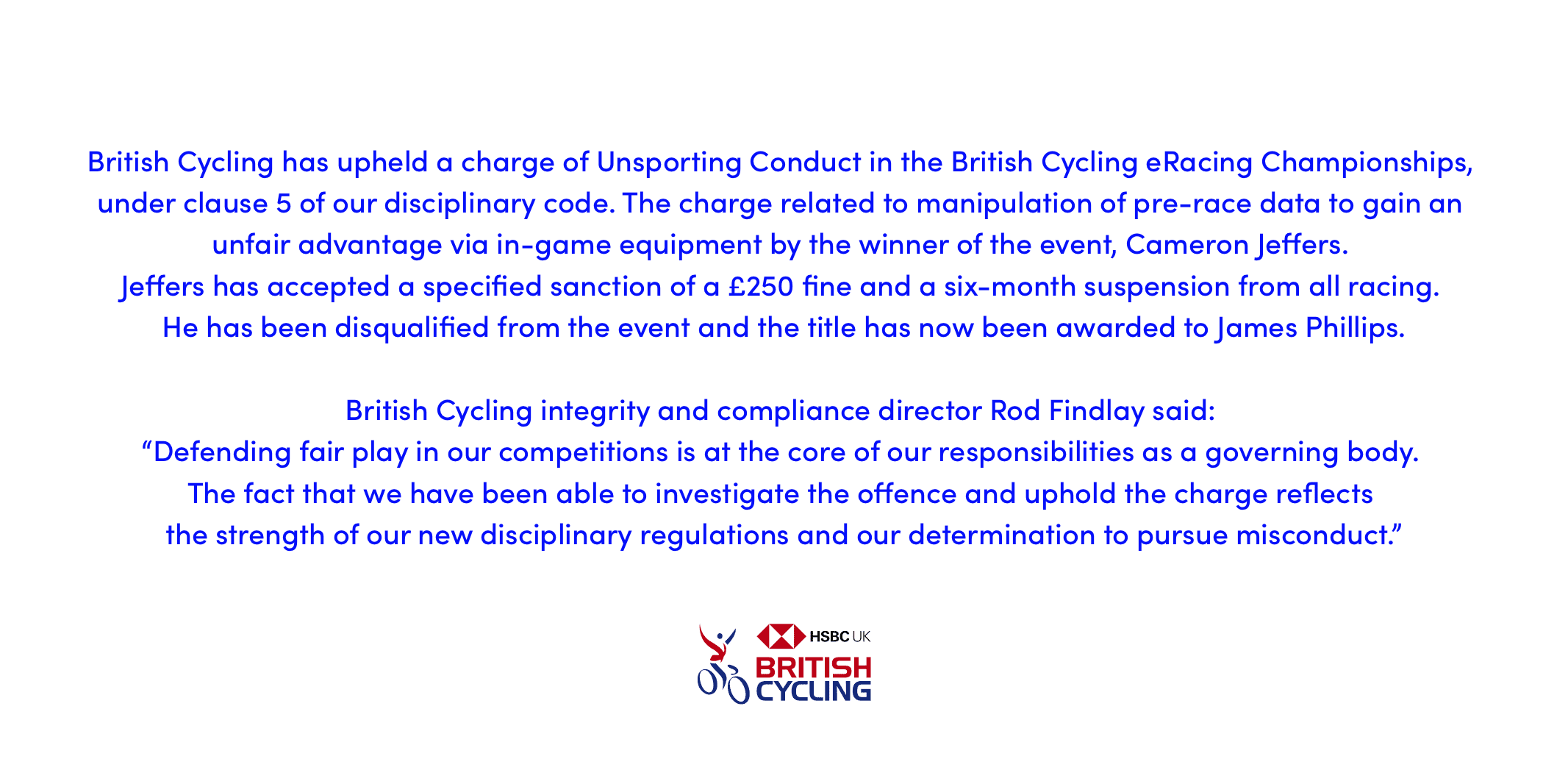

Following an investigation by the sport’s governing body, British Cycling, Jeffers was stripped of the title, was handed a £250 fine, and a six-month ban from all racing. But what Jeffers actually did, in reality, isn’t quite as nefarious as the punishment suggests – basically, he just obtained and used an in-game upgrade that he shouldn’t have had access to.

In Zwift, like with most games, the more you play, the more in game content you unlock. But Jeffers hacked the system by having a “bot” ride for him to complete the achievement goals on his behalf. Ultimately, he used the hack to unlock the Zwift Concept Z1 “Tron” bike, one of the fastest bikes in the game.

According to a statement from British Cycling, Jeffers manipulated “pre-race data to gain an unfair advantage via in game equipment.” Jeffers himself said on YouTube and Twitter: “An ANT+ (wireless) simulator was used to climb the 50,000m in game to unlock the bike, which means I didn’t personally operate Zwift to unlock the bike.”

Zwift’s senior PR manager added further detail saying that Jeffers used the “bot to ride on multiple occasions at 2,000 watts for distances of over 200km with a weight of 45kg.”

The high power and low weight means Jeffers’ in game character went up hill faster than the Hulk crossed with Lance Armstrong, probably.

However, there was no British Cycling rule that said riders couldn’t use external means to unlock in-game content ahead of the event. It’s like winning a bike race on a stolen or borrowed bike, you might not get banned, but the police or competitors might have something to say.

Ultimately, he went on to use the “Tron” bike to win the finals of the British eRacing championships. And because of how he obtained it, British Cycling interpreted his use of the bike as “unsporting.”

It’s clear Jeffers did something unethical, but the scope of how he should be punished is not clear cut.

A heavy-handed reaction

While it’s certainly the right call to strip Jeffers of the title and slap him with a fine for his unsporting conduct, banning him from real-world races too is a bit heavy-handed. It’s almost going by the mantra of “once a cheater always a cheater.” The scope of Jeffers’ cheating didn’t extend into the real-world, so his ban shouldn’t either.

Esports competitors being banned for cheating is nothing new. Earlier this year, 12 professional PUBG players received bans for using a hack which let them know where enemies were hiding in the virtual world.

These bans only ever relate to the esport in which the cheating took place, after all there’s no way they could extend into the real-world. Yet with Zwift as an esport, we’re faced with what could be the first situation where the sport’s real-world governing body also oversees the virtual too.

Up until the national eRacing championships, Jeffers’ participation in Zwift had been to take part in training, inconsequential community races, and to “play the game.” In his own words, he wanted to get the “Tron” bike because it looked cool. He seemingly paid little if any attention to the potential repercussions of his actions.

What Jeffers did, while unsporting, only gave him an advantage in a very specific scenario; when he was riding the “Tron” bike in Zwift. Jeffers’ actions certainly do not extend to the real-world. Now if he had tested positive for a banned performance enhancing substance that would give him a real-world boost too, that’s a very different conversation.

For all its opportunity, this whole debacle has highlighted a bigger issue. How to regulate and sanction esports when they blend almost seamlessly into conventional sports which already have their own governing bodies. With Jeffers’ ban the lines between what is real-world cheating and what is exclusively digital cheating blur.

Road racing and e-racing are two different sports. E-racing has the opportunity to strip away all environmental variables like wind, crashes, punctures, and equipment advantages that could never be removed from real-world racing to create something new. Or it can continue to play second fiddle to the real thing, as it appears to be doing.

We should recognize e-racing is not the same as real-world racing. While athletes may crossover and compete in both, it’s apparent that e-racing is ushering a new world of sport, worthy of its own regulations, rules, and events.

E-racing shouldn’t try to replicate real-world racing on stage for the guffawing of cycling nerds, but rather should be allowed to flourish on its own, to become a unique sport in its own right.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.