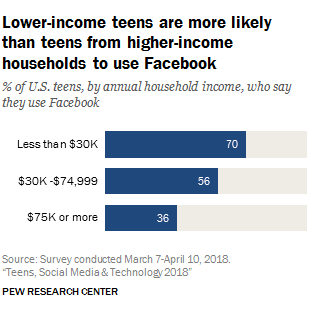

A Pew Research study published earlier this year showed that, statistically, a large number of teenagers from families with lower-than-average annual income still use Facebook. While 36 percent of teens from families making $75,000 or more per year, and 56 percent of teens from the $30,ooo-$74,999 range said they used Facebook, the number rose to a whopping 70 percent when it came to teens in families earning $30,000 or less.

The number is surprising considering that the rest of the research showed Facebook usage had dropped overall among teenagers in favor of Instagram, YouTube, and Snapchat. This isn’t a recent development, either; Another Pew study from 2015 found that Facebook was overwhelmingly the social media site of choice for teens from both lower- and middle-income families. At the time, Snapchat and Instagram weren’t as widely used as they are now, but they were disproportionately popular among richer teens.

It’s an odd manifestation of the digital divide, or the manifestation of inequality with regards to access to digital information. Usually, when we’re talking about the digital divide, we’re talking about those who have the socioeconomic stability to purchase devices and those who don’t. But the gulf between Facebook users from different income brackets suggests it extends even to ostensibly free sites.

A 2016 study by the Joan Ganz Cooney Center showed that, out of 1,200 parents of moderate-to-low income families with children (aged 6-13), 85 percent of those living below the poverty line still owned at least one mobile device. That sounds positive, but there is a catch: not every family has devices exclusive to each member.

According to the study, a full quarter of families below the poverty line surveyed said one of the difficulties with using a phone was that they had to share it with another person. A lot of us take it for granted we have our own devices, but in some families, a tablet or phone is more likely to be a family-wide investment.

Dr. Karen North, clinical professor of communication and digital social media at USC Annenberg offered the following take when asked about the divide:

Right now, everyone has access to computers, but not everyone has personal computers, and not everyone has a smartphone. The people who do have smartphones, not everyone has unlimited data. What would you do if you wanted to interact socially and some number of your friends don’t have their own device? Snapchat and Instagram are almost exclusively mobile activities, and they’re downloads. You either have it on your phone or you don’t. But Facebook, you can log in and post whatever you want from a computer at a library, or from your family’s shared computer. Facebook is set up such that it doesn’t have to be a private device, as opposed to Instagram and Snapchat. So that may be very appealing to kids who don’t have as much personal ownership of devices and technology.

Keep in mind, the 2018 Pew study doesn’t say teens from lower-income families are more inclined to use Facebook over other social media — they use Instagram, YouTube, and Snapchat just as often as their more affluent peers. It’s just that, of the dwindling audience for Facebook, lower-income teens are more likely to have kept their accounts and actually used them.

Dr. North also pointed out that, if even a small percentage of a school-age group uses Facebook as their primary form of social media, it motivates everyone in their network to remain on the site:

Let’s say the majority of kids from lower-income families have smartphones with unlimited data. But what if a significant-but-small percentage — say 10 or 20 — don’t? And what if those kids are core parts of the social experience? What if they’re significant members of friend groups and teams and classes and activities? Then it doesn’t make sense to engage in social activities that exclude key members of the group. So the whole group may gravitate towards something that has easier access for everybody.

Another insight from the Joan Ganz Cooney survey was that the vast majority of parents, when asked why they purchased a smartphone, said it was to “keep in touch with family and friends.”

Professor Lynn Schofield Clark, from the media department of the University of Denver, posited the idea to Quartz that teens from lower-income families might have less of a generation gap, and be less likely to abandon a social media just because their “uncool” parents are using it. They also might have moved around more, or are more likely to be from an immigrant background — meaning they’ll have family in far-flung places and require Facebook as a fundamental (and free) way of keeping in touch.

Point being, there are multiple reasons why teenagers from a certain background might be more inclined to stick with Facebook. It’s instructive to remember that, even when it seems like a social media site is losing “cool” points or something worth criticizing on an intellectual level — as I do to Facebook almost on the daily — it’s still a very important way for lots of people to maintain their social ties for free.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.