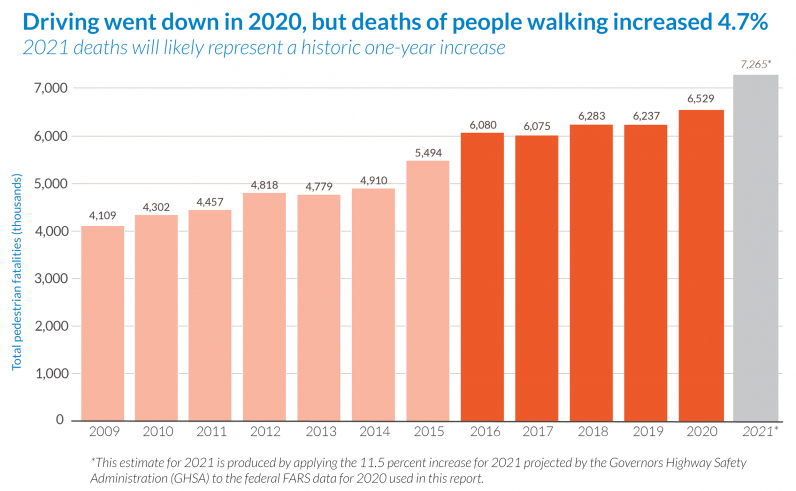

A new report finds that North American streets are getting deadlier for pedestrians. Research by Smart Growth America and the National Complete Streets Coalition reveals that, in 2020, over 6,500 people were struck and killed by cars while walking.

That averages out to 18 people a day — and a deadly 4.5% increase from 2019.

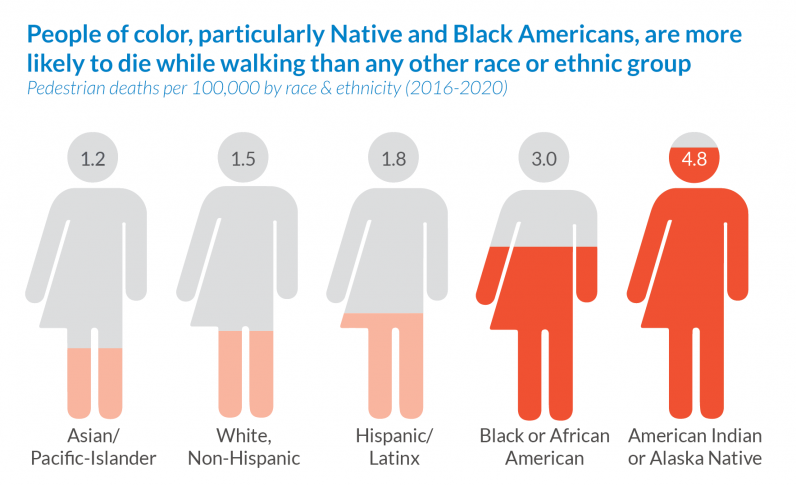

To make matters worse, the burden is not shared equally among pedestrians.

Low-income residents, older adults, and people of color are more likely to be struck and killed while walking.

Black pedestrians are twice as likely to be killed than white, non-Hispanic pedestrians. Native Americans faced risks nearly three times as great.

Sadly, these statistics may underestimate the toll, as hundreds of traffic fatalities are reported without race each year.

Pedestrian neighborhoods aren’t designed equally

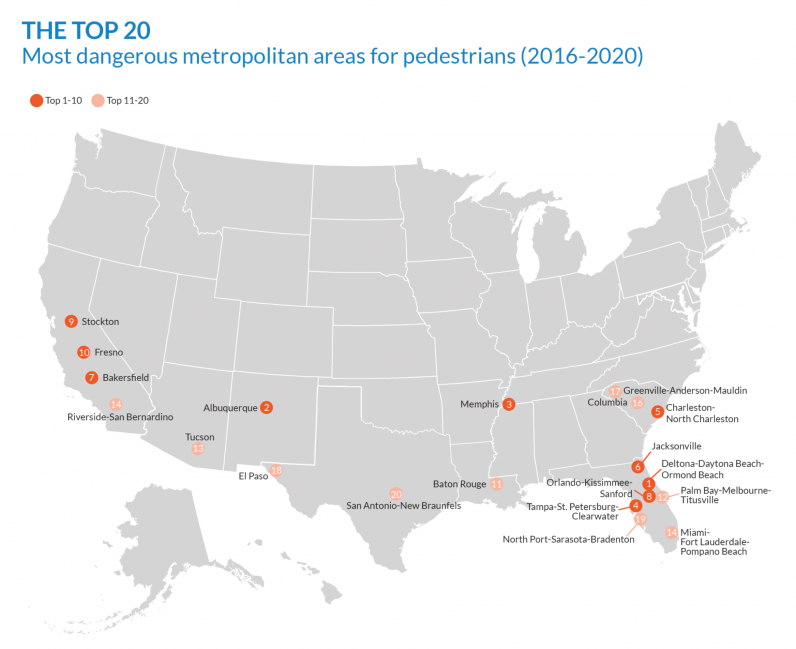

Here are the ten deadliest metros:

- Deltona-Daytona Beach-Ormond Beach, FL

- Albuquerque, NM

- Memphis, TN

- Tampa-St. Petersburg-Clearwater, FL

- Charleston-North Charleston, SC

- Jacksonville, FL

- Bakersfield CA

- Orlando-Kissimmee-Sanford, FL

- Stockton, CA

- Fresno, CA

Florida’s ranking is interesting considering the state signed a policy fully committing to Complete Streets — streets that serve the needs of all users, including cyclists and pedestrians in 2014.

Unfortunately, it seems that these streets aren’t serving Black and Native Americans. And urban design has a role in these deaths.

Black and Native Americans are more likely to reside lower-income neighborhoods. These neighborhoods traditionally have fewer sidewalks and parks, as well as more arterial roads. This leads to higher speeds and more traffic, which results in a higher number of pedestrian fatalities.

Further, people with low-incomes are more likely to live outside of urban city centers, where housing is less expensive. This means exclusion from the safest and most walkable parts of a city, such as downtown and tourist precincts.

These inner urban areas — unlike the outer city — are most likely to benefit from lobbying from retailers associations to improve walkability or smart city pilots that increase safety, such as smart traffic lights and street lights. Compare this to outer regions that may not even have sidewalks to begin with.

And while 2020 may have seen fewer drivers on the road because of the pandemic, the roads became deadlier.

Speed-related kills increased during the pandemic

According to the report, road design preferences speed over safety. As roads became less congested during the pandemic, driver speeds increased. Faster driving increases the likelihood a pedestrian will be killed rather than just injured.

The report was based on over a decade of data from the Governors Highway Safety Association (GHSA), which also noted that the pandemic’s impact on car sales correlates with higher pedestrian deaths.

Newer vehicles generally have better crash avoidance technology than older models and have pedestrian detection as a standard feature.

However, the decline in new vehicle sales in 2020 slowed safer vehicle integration on the road. As a result, pedestrians were less protected than they could have been.

The data also revealed that in 2021 deaths caused by passenger cars grew by 36%. Specifically, SUV-caused fatalities increased by a whopping 76%, and that’s concerning.

The way forward is by investing in safer pedestrianized cities

According to the GSHA, intentional road design can reduce the risk of pedestrian accidents. For example:

- Raised pedestrian crossings (ramped speed tables that span the entire roadway width) can reduce pedestrian crashes by 45%.

- Pedestrian refuge islands provide a safe break point and can reduce pedestrian crashes by 56%.

- Street lighting can help motor vehicle drivers see pedestrians sooner. Overhead lighting outside of intersections can reduce crashes by 23%. The benefit is even greater at intersections — a 27% reduction.

- Sidewalks significantly improve pedestrian safety, as most fatal pedestrian crashes occur in locations without them.

- Painted crosswalks, intersection murals, and other artistic treatments of the roadway surface can improve safety by getting drivers to slow down.

Besides efforts to address disproportionate road risk, there’s also a national effort in North America to address the biggest racial inequity in road design at a local level.

Reconnecting Communities by addressing racial segregation in urban planning

At the end of June, funding applications began for the Reconnecting Communities pilot program, funded by the President’s Bipartisan infrastructure law. $1 billion in funding will help reconnect communities that were previously cut off from economic opportunities by transportation infrastructure.

U.S. Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg, detailed that the program aims to redress historic planning decisions that built road infrastructure such as freeways “directly through the heart of vibrant, populated, communities:

Sometimes to reinforce segregation. Sometimes because the people there had less power to resist. And sometimes as part of a direct effort to replace or eliminate Black neighborhoods.

This inherently racist infrastructure not only led to higher pedestrian fatalities but also increased air pollution near where people live. It can impact property values and prohibit workers from accessing higher-paid jobs due to long expensive commutes.

In response, the Reconnecting Communities pilot will fund local efforts such as high-quality public transportation, infrastructure removal, pedestrian walkways, and overpasses, capping and lids, linear parks and trails, crosswalk and roadway redesigns, complete streets conversions, and main street revitalization.

Vehicle makers are acutely aware of the need to build safer cars. But we also need equity in urban design.

At least now, there’s hard data that maps places where pedestrians are most at risk, and concrete opportunities for solutions led by the communities most impacted. And that’s how we build safer roads.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.