According to a study by the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (IDEA) released late last week, digital technologies will become an increasing factor in European democracy in the coming decade. This is perhaps not entirely surprising; after all, the pandemic shifted much of our lives into the digital realm, why shouldn’t our political participation?

The report, based on interviews with more than 50 government and industry representatives, finds that the market for online participation and deliberation in Europe is expected to grow to €300mn in the next five years, whereas the market for e-voting will grow to €500mn. The respondents also state that there is a “window of opportunity” for European providers of democracy technology to expand beyond Europe.

Authors of the report further believe that digital democracy technology can support outreach to demographics that may otherwise be difficult to reach, such as youth and immigrant communities. This also includes broader populations under difficult circumstances, such as those brought on by the pandemic and Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine.

“In case of war, electronic democracy tools have to be even stronger. Because we understand we have to live for the society and give citizens tools,” said Oleg Polovynko, Director of IT at Kyiv Digital, City Council of Kyiv, and one of the speakers at the TNW Conference 2023.

Not without controversy

Digital democracy refers to the use of digital technologies and platforms to enhance democratic processes and increase citizens’ participation in government decision-making. This is also referred to as civic tech (not to be confused with govtech, which focuses on technologies that help governments perform their functions more efficiently).

Examples of tools include online petitions, open data portals, and participatory budgeting systems, where citizens come together to discuss community needs and priorities and then allocate public funds accordingly.

In a best-case scenario, it has the potential to reinvigorate democracy by allowing citizens to participate from anywhere at any time. In a worst-case scenario, it could be used for disinformation or just plain good old online toxic behaviour.

Furthermore, the discussion of a potential ‘digital divide – who will benefit and who will be excluded due to access or lack thereof to technology – is not one that is easily settled.

Inviting AI into collective decision making

IDEA states that there are more than 100 vendors in Europe in the online participation, deliberation and voting sector, most of whom are active on a national level. The majority of those operating internationally are startups with between 10 and 60 employees, but expanding quickly.

Many of these democracy technology platforms have already begun taking advantage of the recent step-change developments in artificial intelligence to introduce new features or enhance existing ones.

“We foresee a future where citizens and AI collaboratively engage with governments to address intricate social issues by merging collective intelligence with artificial intelligence,” Robert Bjarnason, co-founder and President of Citizens.is tells TNW.

“We advocate for a model in which citizens work alongside powerful AI systems to help shape policy, rather than allowing centralised government AI models to exert excessive influence.”

Following the collapse of Icelandic banks in 2008, distrust of politicians was at an all-time high in the Nordic island nation. Together with a fellow programmer, Gunnar Grímsson, Bjarnasson created a software platform called Your Priorities that allows citizens to suggest laws and policies that can then be up- or down-voted by other users.

Just before local elections in 2010, the open-source software was used to set up the Better Reykjavik portal. Five years later, a poll on the site managed to name a street in the Icelandic capital after Darth Vader (well, his Icelandic moniker of Svarthöfði, or Black-cape, which already fitted well with the names of the streets in the area).

Of course, there have been much ‘weightier’ decisions influenced by the platform, such as crowdsourcing ideas on how to prioritise the City’s educational objectives.

Thus far, over 70,000 of the capital’s inhabitants have engaged with Better Reykjavik. Pretty impressive for a population of 120,000. Furthermore, Your Priorities has been trialled in Malta, Norway, Scotland, and Estonia.

The Baltic tech-forward nation has adopted several laws suggested through the platform, which features a unique debating system, crowdsourcing of content and prioritisation, a ‘toxicity sensor’ to alert admins about potentially abusive content – and extensive use of AI. In fact, Citizens.is recently entered into collaboration with OpenAI, and has deployed GPT-4 for its AI assistant – in Icelandic.

GPT-4 now empowers digital democracy and collective intelligence in Iceland ?❤️ Thnx to a collaboration btw @OpenAI, the government, and Miðeind, we’re launching our AI assistant in Icelandic. Thanks @sama, @gdb, @vthorsteinsson, @cohere, @langchain, @weaviate_io & @buildWithLit pic.twitter.com/LNxAAFe2nf

— Citizens Foundation (@CitizensFNDN) March 19, 2023

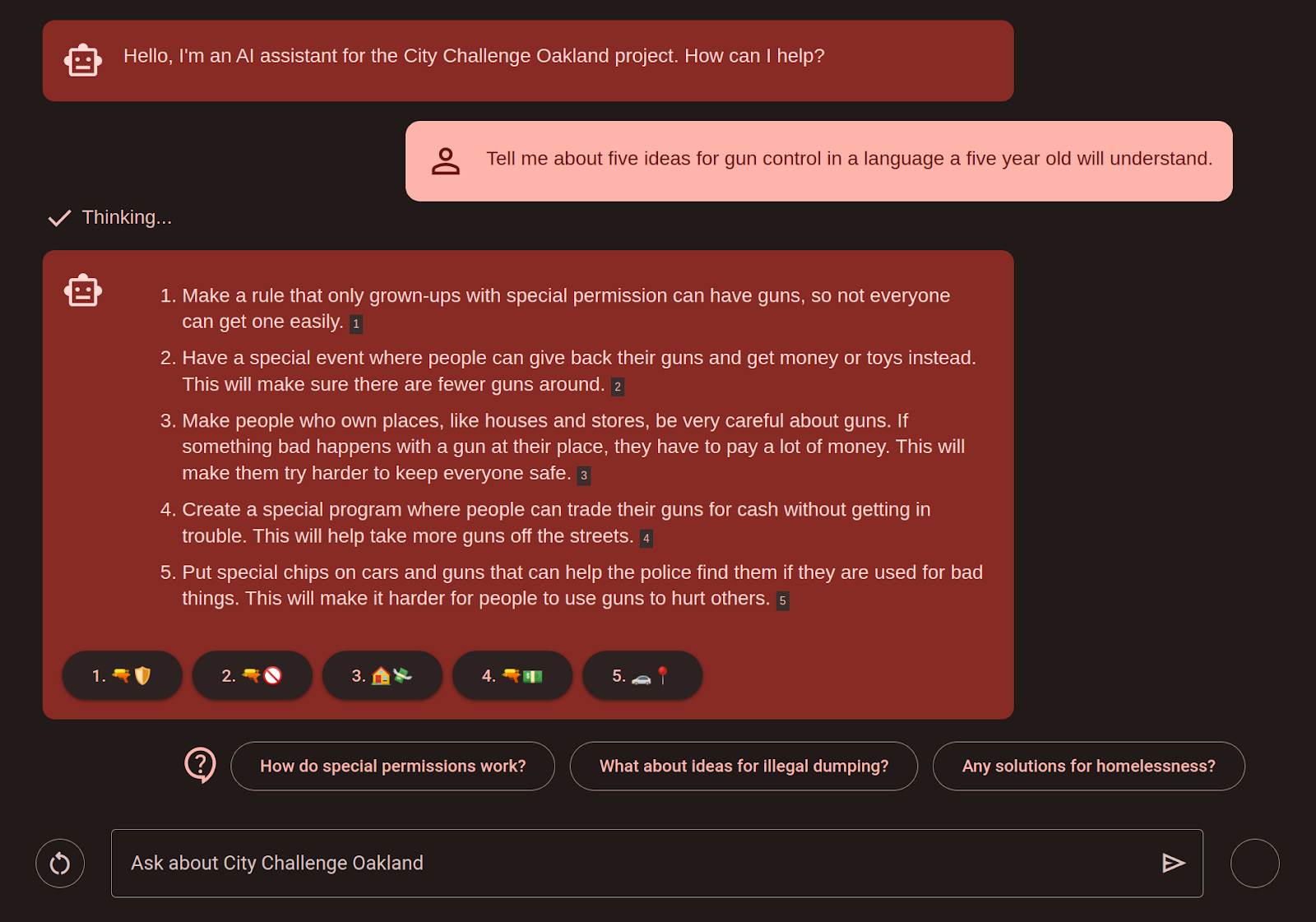

Don’t worry if the language barrier felt a little steep. Citizens.is has been kind enough to provide TNW with a screenshot of the company’s AI assistant in action from a project in Oakland, California.

Other examples of civic tech focused companies in Europe include Belgium-founded scaleup CitizenLab, which now works with more than 300 local governments and organisations across 18 countries, and Berlin-based non-profit Liquid Democracy. Liquid’s open source deliberation and collaborative decision-making Adhocracy+ software platform also helps facilitate face-to-face meetings throughout the timeline of participation projects.

Gaining the trust of the citizen

The main product trends identified in the IDEA study are: artificial intelligence, voting, and administration and reporting. Meanwhile, it also found that it is important to address issues around inclusiveness, data usage, accountability and transparency, and to develop security standards for end-to-end verified voting.

One solution proposed is the introduction of a Europe-wide quality trust mark for democracy technologies.

“If a citizen can trust the banking application to make transactions, then equivalently our service can be trusted to make the citizen’s voice heard,” stated Nicholas Tsounis, CEO of online voting platform Electobox. “We want people to trust this application because we know that it is there for them to protect the right to speak and vote.”

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.