The crypto crash has spooked many investors, but blockchain bros have high hopes for one nascent application: GameFi.

A portmanteau of “game” and “decentralized finance,” the model offers a chance at earning cash by gaming. Players who complete in-game tasks are rewarded with crypto and NFTs, which can then be traded for real money.

It’s a tempting pitch on paper. But play-to-earn shows signs of plateauing before it enters the mainstream.

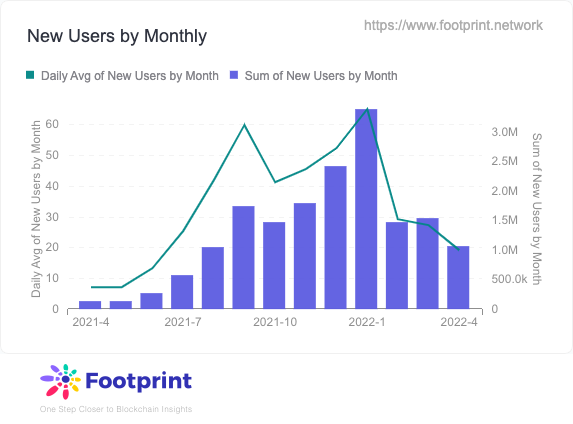

In April, active users shrunk by 24.9% to 9.22 million, while transaction volumes fell by 73.4%, according to Footprint Analytics,

A big barrier to mass adoption is simple economics: a sustainable market needs more money coming in than going out.

This primarily requires a constant stream of new users to subsidize the established ones — a model that’s been called a pyramid scheme.

The accusation has been leveled at Axie Infinity, a Pokemon-style battle game that exploded in popularity last year.

Thousands of people have played Axie as full-time jobs — with mixed results.

Play-as-you-go

Axie users typically invest hundreds of dollars for a starter pack of the NFT creatures. The company makes money by taking a cut on every marketplace transaction.

Some users lower the entry by forming groups called “guilds.” This involves owners of the NFTs lending them to players in exchange for a share of the profits.

It’s risky for the owners, who can invest vast sums in the volatile assets, and the potential gains for the player are lower — but there are also benefits.

Earnings can still be substantial — particularly in the emerging economies that are the game’s biggest markets — and guilds reduce the financial risks of players.

Yet this doesn’t resolve the fundamental issue: new players need to replace the ones who cash out.

This wasn’t a problem when Axie was adding more users each month than those it already had. But when growth slowed and the token price slipped, player earnings dived.

After months of incredible growth, the daily earnings of the typical player of Axie Infinity (a "scholar" in the Philippines) have fallen below the Philippines' minimum wage line for all but the high ranking players, and even they have seen earnings decline since August pic.twitter.com/ejidWkWc1G

— Lars "Totally Texas" Doucet (@larsiusprime) November 12, 2021

Axie suffered a further setback when hackers stole $625 million of cryptocurrency Ronin, the blockchain behind the game. The attack is the largest crypto heist to date, according to REKT Database.

Axie’s maker pledged to reimburse affected users, but the game’s coin value and player numbers have continued to dip.

In May, Axie’s daily active users fell below 1 million for the first in eight months. The figure had peaked at over 2.7 million in November.

Fun thirst

Axie’s decline has reverberated across the GameFi community. Companies in the sector are now reassessing their business models.

At a panel discussion during the BlockDown conference last week, GameFi execs centered their strategies on prioritizing pleasure over profit.

“It’s going to come back to web2 fundamentals of needing a good game to survive,” said Corey Wilton, co-founder of Pexabay, a play-to-earn horse racing simulator.

AAA games, however, have development costs that GameFi firms can’t afford.

FancyStudios, which creates 8-bit games is trying to overcome this hurdle by tapping into the nostalgic appeal of retro classics.

Eric McIntire, the company’s CCO, hopes this shifts the user focus from play-to-earn to play-and-earn.

“We want you to happen to earn money while you’re doing something that you enjoy doing anyway,” he said.

“While you’re standing in line for a coffee, we want you to pay for the coffee by playing a game that you’re having fun playing anyway.”

Ultimately, McIntire is targeting a transition to “play-to-own,” which encourages users to keep their digital assets in the game.

They still earn rewards, but instead of exchanging them for real money, they can use them to shape the in-game experience.

This could incentivize user retention — but the games will need mass appeal.

“We had a 2D horse racing game that’s in an MVP basically — not even an alpha — and it had $200 million going through it,” said Wilton.

“I think that’s probably an indicator that they’re not here for the f’ing game.”

Game on

GameFi also needs support from regular gamers — who have proven hostile to crypto projects.

Ubisoft’s NFT plans, for instance, sparked a furious backlash from fans. The YouTube announcement was disliked by more than 95% of viewers.

GameFi firms aim to eventually seamlessly integrate any blockchain elements.

In a similar manner to paying with a credit card, gamers would use the mechanisms without considering how they work.

“I think eventually things are going to transform and it’s just going to feel like a game,” said Wilton. “But I’d say we’re probably five-to-10 years away from something like that.”

In the embryonic world of GameFi, businesses are still searching for a sustainable formula.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.