![[Best of 2019] NATO CCDCOE strategist: Die Hard 4 is the perfect way to describe real cyberwarfare](https://img-cdn.tnwcdn.com/image?fit=1280%2C720&url=https%3A%2F%2Fcdn0.tnwcdn.com%2Fwp-content%2Fblogs.dir%2F1%2Ffiles%2F2019%2F04%2F23n-1.png&signature=7224e6ae299162201fb70f5493384988)

When I entered a snow-covered military base in Tallinn, Estonia, on a crisp winter morning to do interviews on cyberwarfare, I didn’t expect the fourth Die Hard movie to be part of my research.

“The movie came out more than 10 years ago, so you’d expect it to be outdated, but its depiction of cyberwarfare is actually very realistic,” said Siim Alatalu, a Strategy Researcher at the NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence (CCDCOE).

Wait… Live Free or Die Hard, a movie where John McClane battles a fighter jet with a semi truck, is realistic?

“What makes it realistic is the targets the bad guy goes after to achieve his goal,” Alatalu explains. “The targets are things around us in daily lives, anything from traffic lights, to power plants, to gas refineries. These are all things we don’t really need to know how they operate around us — but at the same time — if somebody learns how to manipulate them, they can change the way we live.”

Cyberwarfare is something we’ve all seen in movies — like Die Hard — but most of us don’t fully grasp it. How’s it different to conventional warfare? How do you train and prepare for cyberattacks? Is this really something we need to worry about and what does the future hold? That’s what I hoped to learn more about at the CCDCOE.

The game has changed

“I was taught during my military service days that in a conventional war, you’d need to have about three times as many men as your enemy to successfully attack. This is because the defender is basically always in a better position than the attacker,” Alatalu explains. “But the one who knows the vulnerabilities best always has a critical advantage.”

What’s different about cyberwarfare is the balance between attacker and defender is changing as manpower plays a different role, and the concept of knowing vulnerabilities is becoming increasingly important. “Therefore, I think a good defense strategy is not to know your enemy, but knowing how your enemy thinks,” Alatalu added. “To do that, you need to put yourself in your enemies’ shoes, identify your own vulnerabilities, and understand which could be the critical one.”

Cyberwarfare is changing the nature and scope of conflict, as it goes so far beyond ‘cyber’ and actually touches peoples’ lives. That’s why nations need to be alert and prepared for attacks. It can be difficult, as cyberwarfare can affect almost every aspect of civilian life and technology. As such, Alatalu says a big part of dealing with crisis is simply having a good answer to the question: who are you gonna call? Well, it certainly isn’t the Ghostbusters.

Welcome to cyberwarfare boot camp

In order to help countries answer that question, the CCDCOE hosts its yearly boot camp, Locked Shields, in Tallinn for the 21 nations (NATO and non-NATO members) that are behind the cyber defense hub. And no, it’s not operated by a drill sergeant yelling at lowly ‘maggots’ or people running around in a snowy Estonian forest. Instead, Alatalu sums it up more succinctly:

“Lot’s of pizza and Coca-Cola.”

But as you can see from the intense video of last year’s exercise, there’s a lot more going on than just pizza and coke.

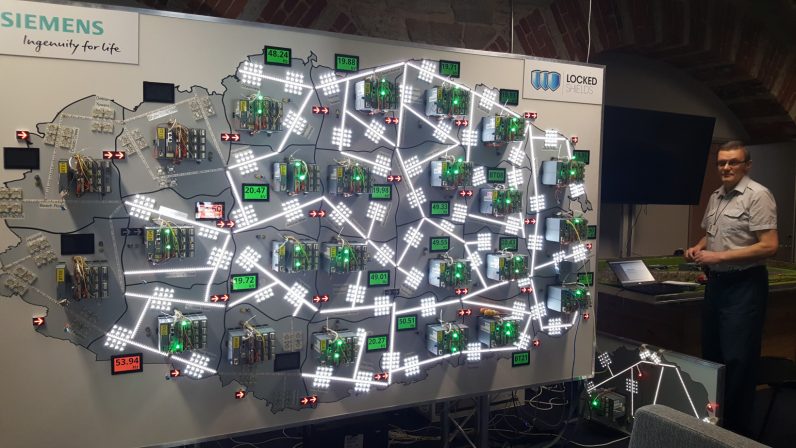

Locked Shields is a massive defensive exercise that enables cyber security experts to enhance their skills in defending national IT systems and critical infrastructure under real-time attacks. It’s technically not ‘in Tallinn,’ as each member nation of CCDCOE forms a Blue Team in its own country to best simulate real situations. The Blue Teams then get two days to defend against over 2,500 attacks, spread across 4,000 systems, carried out by the Red Team based in the CCDCOE in Tallinn.

What’s unusual about Locked Shields as a military exercise is the fact it goes beyond military personnel — just like cyberwarfare. A big part of the simulated attacks target power grids — which in larger countries can require up to 100,000 specialists to maintain — so it’s probably a good idea to have some experts in the room when these facilities are being hacked. As Raimo Peterson, the Head of Technology Branch at the CCDCOE puts it: “We’re cyber experts, not power grid experts.”

Locked Shields also makes sure to show just how powerful attacking positions can be when exploiting vulnerabilities. There’s only one Red Team going against 20 or so Blue Teams, but the Red Team has a few months to prepare and has its own exercise, Crossed Swords, to hone its skills. The defending teams, however, need to react in real-time. The Red Team also has experts from companies that support the drill — like Siemens and Ericsson — which attack the same systems they helped to create.

What’s interesting about the exercise is it involves protecting many of the same targets that were attacked in Die Hard (I guess it really is a perfect example). Cyber military officials learn how to deal with threats with the help of civilian experts who know the systems inside out. This is incredibly important as the scale of cyberwarfare makes coordination one of the key defensive qualities. So when an attack comes, all the members of CCDCOE will know exactly who to bring to the table and how to defend their services.

But do we really need to be so paranoid? Sure the US, China, and Russia might be hacking each other, but do other countries need to worry at all?

Why Estonia cares about cyberdefense

Estonia knows better than anyone that it isn’t just the bigger countries that need to worry about cyberattacks. Back in 2007, Estonia was hit with a brazen cyberattack which targeted foundational websites of Estonian society, like sites of parliament, banks, ministries, newspapers, and broadcasters. Journalists couldn’t publish articles, ATMs stopped working, and government agencies couldn’t communicate.

The attack, which has been referred to as the world’s first cyberwar, came after a dispute due to Estonia’s decision to relocate a statue of a Red Army soldier in Tallinn — something Russia didn’t like. Although it’s never been proved, the general consensus is that the Kremlin was behind the attack — making it a watershed moment in the history of warfare.

“All of a sudden you had a nation state being cyberattacked by another nation state,” says Alatalu. He clarifies that it wasn’t an ‘attack’ in the legal sense, as it wasn’t covered by international law of armed conflict, but the effects of the aggression were truly felt by Estonians.

Up until that point, Alatalu says that Estonia had been trying to bring up the importance of preparing for cyberwarfare with fellow NATO members, but wasn’t met with much enthusiasm or understanding.

“It’s quite difficult to put something seemingly technical and raise it to become politically very important and spark decisions to be made,” Alatalu explains. All the focus back then was on operations and around the situation in Afghanistan, so cyber became a tech specific issue. “The attitude was that cyber was something the techies could handle, just restart your computer kind of thing.”

But this all changed with the 2007 cyberattack on Estonia. NATO and other nations around the world woke up to the direction conflict was taking and started following Estonia’s lead. CCDCOE was established in 2008 in Tallinn, partly due to Estonia’s tech-minded approach, and quickly grew in size — currently improving cyberdefenses of 21 countries around the world.

The future of cyberwarfare

Even though it required a big change in how countries think about defense and new exercises like Locked Shields, cyberwarfare is still very much based on what every conflict in the last thousands of years has been built on: humans.

“Cyberwarfare eventually comes down to the human brain. Fortunately, it still requires a human to operate all the code and launch attacks,” says Alatalu. Tactics, targets, and intent are still shaped by humans, and we can therefore adapt and defend against them.

The NotPetya attack of 2017, which disrupted services spanning from Chernobyl’s radiation detection system to US hospitals, was for example targeted against Ukraine — just like the attacks against Estonia a decade earlier. Motivations and executions were all shaped by the human brain to begin with; the only difference is the effects weren’t contained to the intended target as the level of global connectivity was much more intense — making the attack felt all around the world.

“But all of this might change as we might be looking at a totally new balance when artificial intelligence really kicks in,” says Alatalu. AI is beginning to revolutionize almost every aspect of our lives, so it makes sense it might change cyberwarfare as well. But seeing that AI can come up with solutions and approaches completely different to humans — like AlphaZero’s ‘alien’ chess — does that mean we might see ‘alien’ warfare in the future?

“I’d prefer not to think about this possibility,” Alatalu answers earnestly. But it’s clear to him that when AI really enters cyberwarfare, whoever has the best AI will have a significant advantage. Adaptation seems to be the key, and countries cannot be slow to adjust like at the beginning of the cyberwarfare era.

With increased global connectivity and technological development, we have to be ready for any type of cyberthreat and we’ll continually have to update our defenses — we can’t just count on John McClane to save the day.

TNW Conference 2019 is coming! Check out our glorious new location, inspiring line-up of speakers and activities, and how to be a part of this annual tech bonanza by clicking here.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.