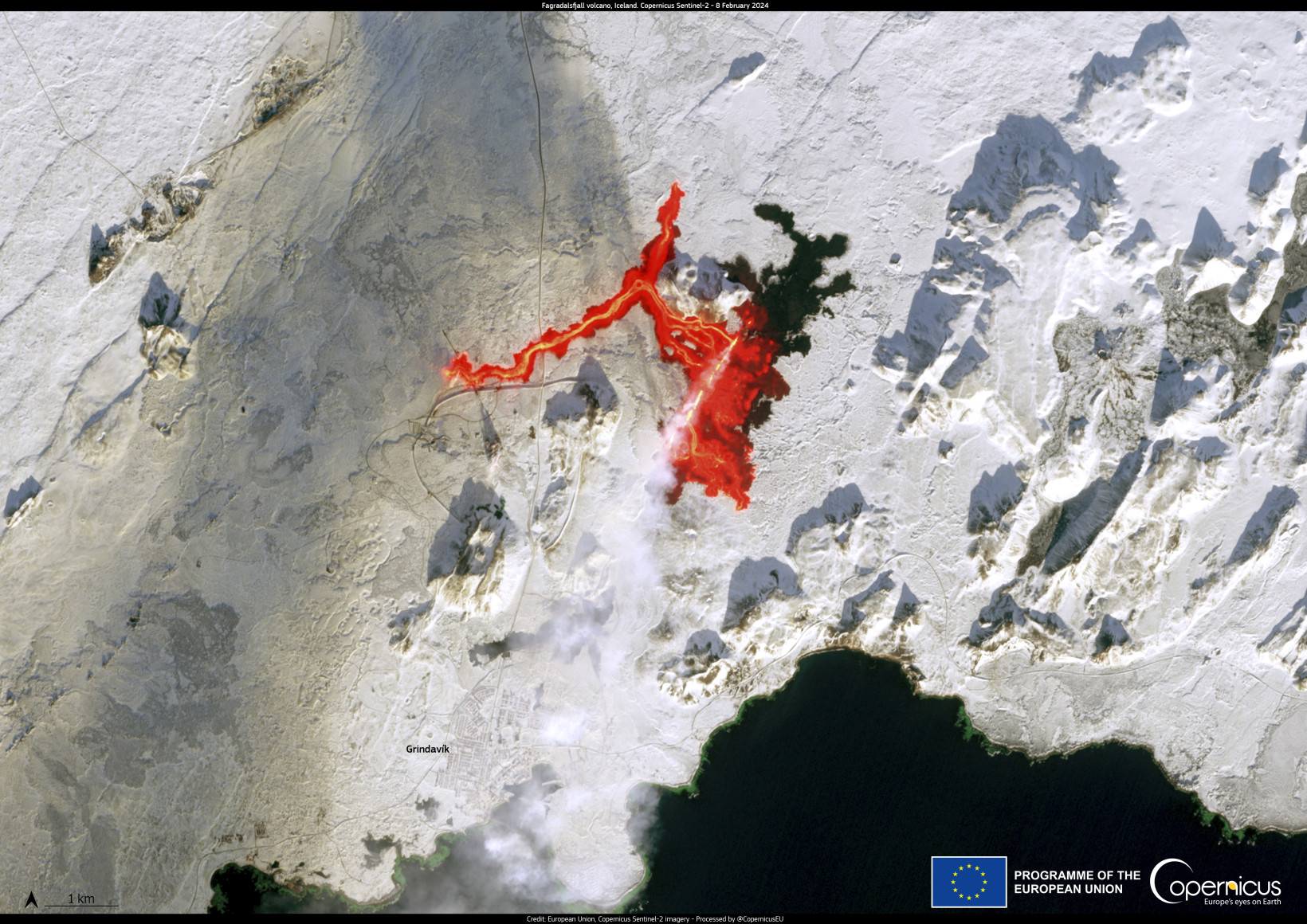

On Saturday, a giant 3-kilometre fissure opened up in the ground on the Reykjanes Peninsula in Iceland, sending a river of molten lava flowing across the landscape.

The eruption is the fourth and largest to hit the region since December. It has forced some 3,800 residents from the nearby town of Grindavik to evacuate. Many have said they have no plans to return.

Another view of when the #eruption started a short while ago in #Iceland. The ground just opens up and boom! Just amazing!!! ?

Speed X20 pic.twitter.com/oXEeub7MbB

— Volcaholic ? (@volcaholic1) March 16, 2024

The Icelandic Meteorological Service uses instruments like seismometers to measure the Earth’s movement, multiGAS machines to measure volcanic gases, infrasound monitors to listen for underground explosions, and GPS units to detect changes in the position of a volcano.

These tried-and-tested tools give scientists a glimpse into the inner workings of a volcano. But newer technologies are emerging that could deepen our insights even further.

“It is currently impossible to accurately forecast a volcanic eruption, but there are ways to improve predictions and disaster response,” Stéphane Ourevitch, expert advisor to the EU’s Copernicus space programme, told TNW.

Satellites, drones, and AI can improve the accuracy of predictions and help us monitor their impacts. This could provide lifesaving information for the 500 million people that live in volcanic zones worldwide, and reduce damage to infrastructure.

Eyes in the skies

Satellites flying above us provide a wealth of real-time data on volcanic activity.

The EU’sCopernicus Sentinel-1 satellites are used across the world by volcanologists to predict eruptions.

Sentinel-1 is equipped with a system known as interferometric synthetic aperture radar (SAR) that detects minute changes in Earth’s crust, which could signal an upcoming volcanic event. Researchers in Italy have used this data to develop a tool to monitor the Campi Flegrei caldera near Naples, one of the world’s most dangerous super volcanoes.

US scientists have also successfully tapped heat-sensing satellites — like Sentinel-3 — to monitor the temperature of active volcanoes, which tend to heat up months or even years before an eruption. This application could potentially provide an early warning system.

In December, UK startup OpenCosmos launched a satellite on behalf of the Institute of Astrophysics of the Canary Islands to monitor volcanic activity and wildfires in the archipelago, which in 2021 was hit by a huge eruption that cost almost $1bn in damages.

The satellite’s primary payload is DRAGO-2, a compact uncooled camera operating in the Short-Wave Infrared (SWIR) range — which provides a viewpoint invisible to the human eye.

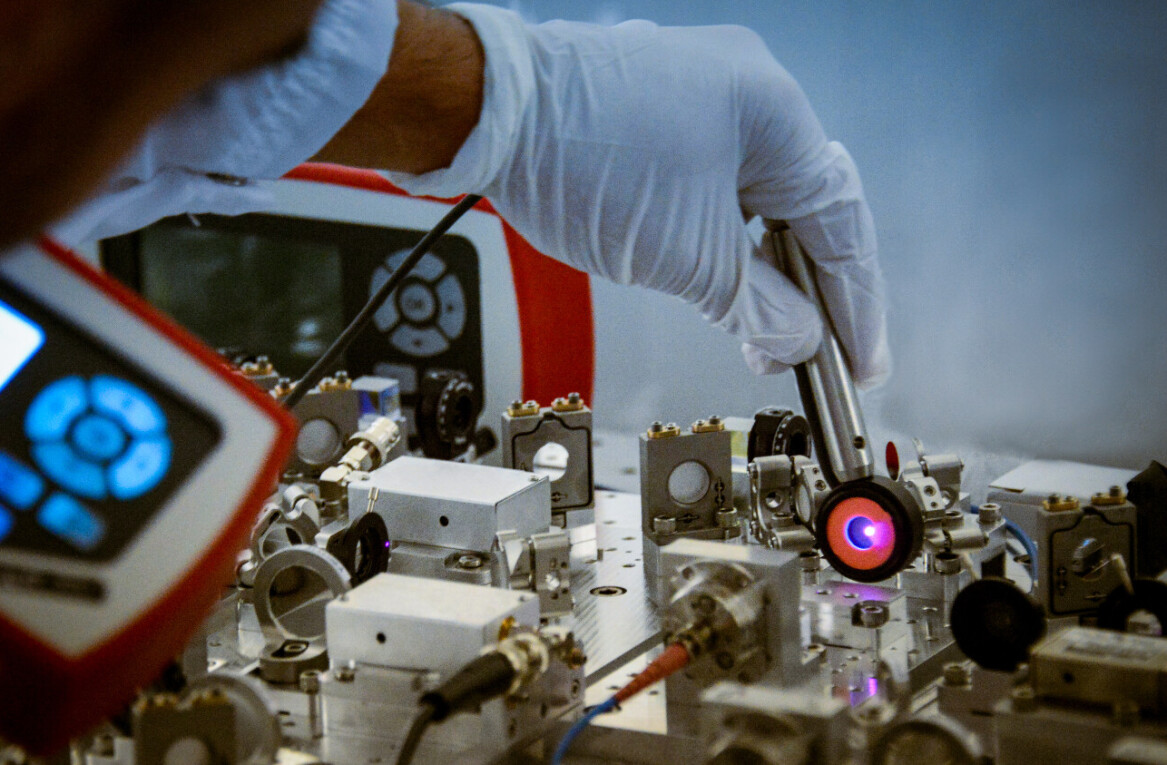

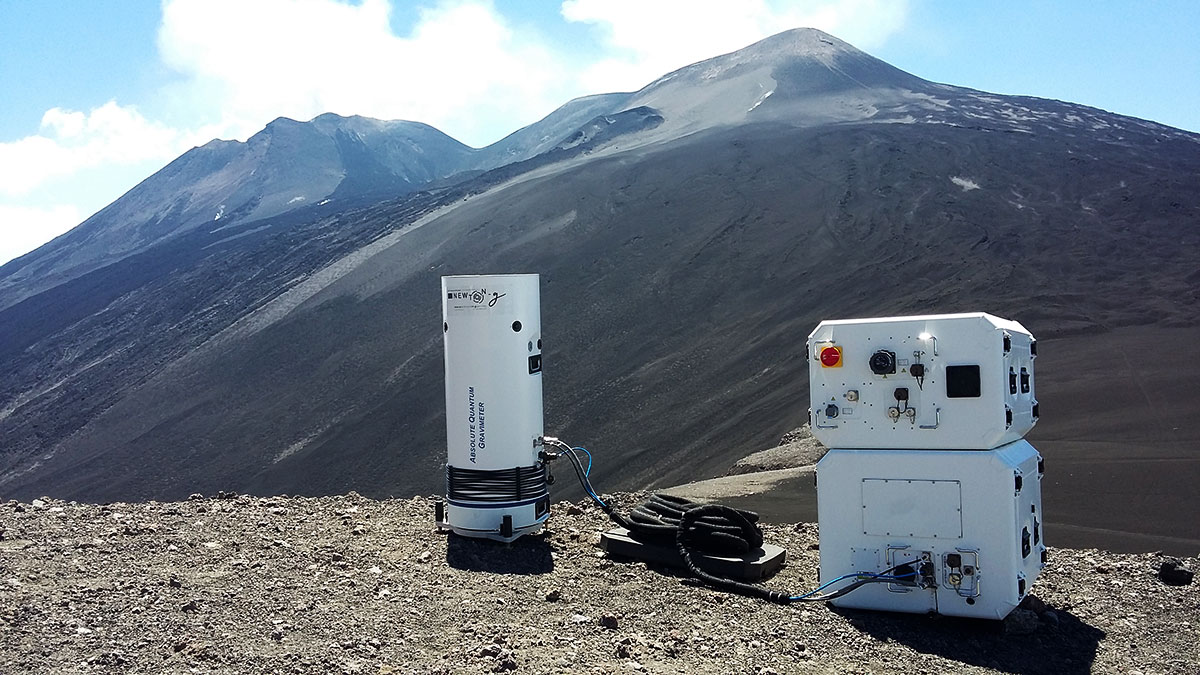

But there’s another, largely untested technology that could prove a game-changer — gravimeters. Actively moving rock, gas, water, and magma alter the density of the Earth’s crust, which leads to measurable changes in gravity. These instruments measure those changes, but are expensive and often impractical to use in such extreme conditions.

In 2021, an EU-backed project installed a first-of-its-kind quantum gravimeter on the slopes of Mount Etna — Europe’s most active volcano. The new instrument measures the acceleration of a laser-cooled atoms in vacuum, and was designed to be smaller, cheaper, and easier to use in the field. Tests are still ongoing.

“Researchers are also working on gravimetry satellites that detect changes in gravity from space,” Ourevitch told me.

Satellites like those from the Copernicus component of the EU Space Programme add to the wealth of information provided by ground-based equipment.

Essentially, scientists are swimming in data; they just need to figure out what to do with it in order to speed up their predictions.

Here’s where machines come in handy.

AI modelling

AI models can analyse seismic data, satellite imagery, and sensor readings to detect subtle precursor signals and identify patterns that may indicate an impending eruption.

In 2018, Italian scientists created an automatic warning system that successfully predicted 57 out of 59 eruptions of Mount Etna over a period of nearly a decade starting in 2008.

Last year, scientists at the University of Bristol trained a machine learning algorithm on more than half a million Copernicus Sentinel-1 images with the aim of forecasting eruptions on a global scale. The algorithm sorted through the images, flagging sixteen that showed deformation, an early precursor for an eruption.

“This study is the first to demonstrate the powerful combination of automatically processed satellite data and machine learning on a large global dataset, to detect volcanic deformation,” said Fabien Albino, remote sensing scientist and co-author of the research.

“Although this is a retrospective analysis, the ultimate aim is to develop a real-time monitoring and alert system that will be used in combination with other sources of information to support evacuations and mitigation efforts,” he added.

Also in Italy, ESA is tapping another technology — drones. Last year it trialled a prototype drone, called Pathfinder, designed to monitor emergency situations and guide the collection of critical samples. The drones could also identify individuals in distress and expedite rescue efforts.

Drones are also being trialled as a safer way to collect gas samples right at the heart of a volcano, where people couldn’t safely go.

While the application of technology like satellites, drones, AI and gravimeters for managing volcanic eruptions is still in its infancy, as these systems mature their adoption will likely become more widespread.

Who knows, maybe in the near future “volcano tech” will become the next hottest technology trend.

Update (19:45PM CET, March 22, 2024): We previously referred to the Copernicus sentinel satellites as belonging to the European Space Agency. However, Copernicus is the Earth observation component of the European Union Space Programme.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.