Two weeks ago, I gave away loads of my personal information to a stranger. Why?

I attended the Black Box Bellagio, a gambling event taking place in Amsterdam, which, in their own words, is “an unusual casino that won’t take your money, but is after your freedom, integrity, and private data instead. Play with the (un)fairness of expected values and chances, predicted risks, and giving up your identity.”

The event was an art project, designed and developed by the Dutch artist Roos Groothuizen and was hosted as part of Waag’s, Project Decode, a project aimed to raise awareness and inform citizens about issues regarding digital privacy and personal data.

A token for your privacy

Before entering the event, you had to stop by a booth to pick up casino tokens. The booth had a list of things you needed to show, in order to get these tokens. The first one was: Do you have a smartphone? If yes, you get a token worth 1000 ‘privacy units.’ Do you have the Facebook app on your phone? If yes, you get an additional token worth 500.

The list then went on to name a bunch of different apps that would each get you more tokens. Furthermore, if you could provide proof for certain facts about yourself, such as whether or not you have a university degree, a full-time job, more than 22,000 euros in your bank account, and even whether or not you were currently on birth control (creepy, I know).

As I read through the list I immediately started to think of how I was supposed to prove all these things. I sure wasn’t about to let those sweet tokens get away, so I did what I could. I showed my driver’s license, I found a picture on my phone of my university diploma and showed it, I even opened up my email account to show proof of my occupation.

It wasn’t until I reached the questions about my bank account and birth control usage that it dawned on me there was actually a limit to how much I wanted to share. Enough was enough. Oh well, I had a fair amount of tokens to start with anyway — I’d just have to win more from my fellow casino-goers.

I entered the casino with a bunch of stickers on my shirt, that each indicated that I had a job, a university degree, and a driver’s license — which I had gone out of my way to prove that I had.

The games

The casino offered three well-known gambling games: Poker, blackjack, and roulette. The roulette game was the easiest one to access at first, so I headed over to the table, ready to chip in.

Once there, I noticed that certain slots were blocked for some players. One of the slots were covered with a sign reading: “You can’t bet here if you’re overweight.” That made me raise an eyebrow, but I still went on with the game. Later, another slot was covered with a different sign that read: “You can only bet here if you have a full-time job”.

I didn’t understand the meaning of this immediately, but Roos Groothuizen, the artist behind the event explained that this was done to illustrate how insurance companies discriminate against us, based on our statistics:

Insurance companies use these kinds of data about us to figure out how risk-avert we are. People who live a healthy life or don’t smoke, will get a discount on their insurance, for example. But when we let these statistics become our personality, they don’t represent us as people any more.

When we use data like this, it overgeneralizes people in order to fit them into an idea of “the average young person,” or “the average overweight person,” but the truth is that these statistics don’t necessarily speak the truth – the average person doesn’t really exist.

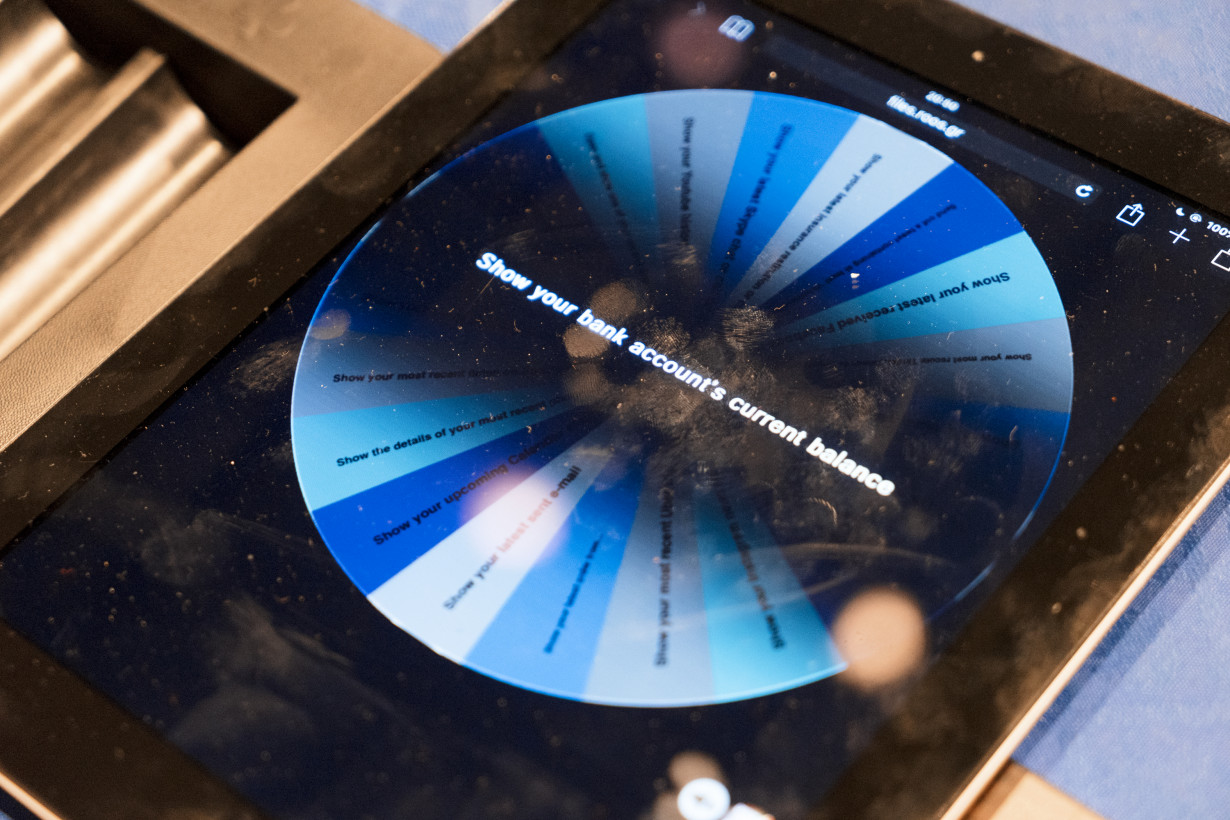

Next up was poker. Before I could access a seat at the table, I noticed the dealer was sitting with an iPad in his hand. The screen showed an image of a wheel that the players regularly chose to spin. In this poker game cheating was allowed, but for a price. You could choose to peak into another players’ cards or ask to be dealt a different card than the ones already in your hand.

To do this, you had to spin what Groothuizen calls “the wheel of misfortune.” The dealer would bring up the iPad, spin the wheel and it would ask you to do something before you could cheat at your pleasure. For example, the wheel would tell you to show your last received email, Whatsapp message, or your five last taken photos. It could also ask you to open your Health-app to show how many steps you take in a day or show your last five significant locations.

Lastly, there was blackjack. As it is with blackjack, you play against the house, and when the house won at this particular casino, it would take control of your online identity. For each loss, the house would tell you to like a certain Facebook page or ask to enter a particular group.

This could be certain radical political parties – like the Dutch party of the far-right politician, Geert Wilders, or the Partij voor de Dieren (Party for the Animals). You could also be told to join groups like “Mamas to be” or to like a radical page called “Atheists against Islam.” This particular game was designed to illustrate how much we care about our online identity.

“It was really funny to see how much we care about how we come across online,” Groothuizen explains, “our online identity is such as curated thing, it might not even be the best representation of us as it is, but this way we played a bit with people’s integrity and it was so interesting to see how people reacted to what stuff they were told to like.”

Play for thought

I was pleasantly surprised that the event did actually spark some interesting thoughts on how digitalization and data collection has altered how we’re being treated, how we think of ourselves, and how our views on privacy and personal information have changed.

I learned that – even for a privacy slob like me – there’s a limit to what I want to share, and I draw it at exchanging information about birth control for casino tokens.

But one of the most notable things was how uncomfortable and, at the same time, fun the experience was. Literally pulling out my phone and showing strangers my significant locations felt weird and wrong, but perhaps it wasn’t much different from what I do online all the time. Having to enter a group called “Mamas to be”, when I have no intention of becoming a ‘mama’ anytime soon crossed several limits, but really showed how much my digital persona means to me.

The event successfully managed to pull our digital life into the actual physical world, and it struck me how separate these lives really are. There is loads that I do online that I might never do offline (sounds shady but I know I’m not the only one). There’s also tons of information about me floating around on the internet, that somehow says everything and nothing about me at the same time. My online personal information can be abused, but it still doesn’t capture me entirely as a person.

But was the event trying to teach us something – to change something? Groothuizen admits, that she has no idea if that’s the case.

I just think these topics are extremely interesting, and I think it’s good to be aware of what is happening when our data is up for grabs by almost anyone. But I have no good solution on what to do about it, and I think that’s also what I want the main takeaway with the project to be.

It’s this feeling of helplessness, we know that this entire thing is messed up, but we have no idea how to deal with it. I think as a start, it’s most important to be aware.

If you want to try another way to throw away your personal data (instead of logging into Facebook), you should check out the Black Box Bellagio casino yourself. Groothuizen will host another privacy casino night at the London FutureFest on July 6 and 7.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.