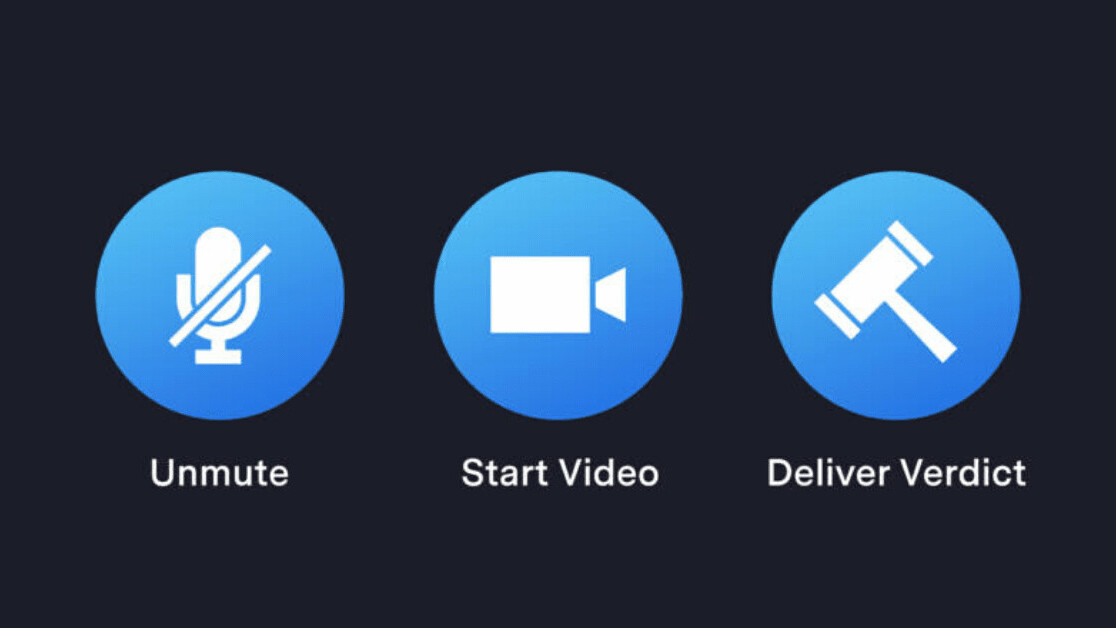

On the morning of May 18, Judge Keith Dean of the Collin County District Court in Texas thanked the potential jurors in front of him for coming and performing their civic duty, as always. Then he and Judge Emily Miskel gave some new, unusual instructions: Tell your roommates to leave the room when we tell you to. Stay plugged into an outlet. And no Googling about the case in another tab!

It was what officials believed was the country’s first wholly online jury trial, gone virtual because the coronavirus has made it dangerous for people to pack into a courtroom in person. This was a minor case—a summary trial of a civil case against an insurance company, with a nonbinding verdict—but a milestone nonetheless. And as the global pandemic stretches on, this experiment with video hearings could too.

But while holding an entire trial by video is new, some jurisdictions have held some types of hearings over video for years. So, what have they learned about the effects of remote courtroom proceedings?

Higher bail amounts

Two-way video technology entered the courtroom almost 50 years ago, believe it or not. Illinois first used a primitive videophone for bail hearings in 1972; in the next decade, Philadelphia and Florida’s Dade County adopted closed-circuit television systems for arraignments, according to the National Center for State Courts. By the mid-1990s, some courts were transmitting video over PCs’ local networks (LANs), others by fiber-optic cables in the telephone system, and others by satellite transmission.

Video hearings have been most commonly used for pretrial initial appearances (also called bail hearings, or bond hearings), in order to save the cost and risks of transporting defendants from the jail to the courthouse. By 2009, when the Pretrial Justice Institute surveyed pretrial programs in the U.S., 57 percent were using video for initial appearance conferences.

Along with convenience and efficiency came some unintended consequences, though. Cook County, Ill., started using closed circuit TV for most bail hearings involving felony cases in 1999. Anyone who had been arrested in Chicago over a 24-hour period was shuffled into a holding pen in a Chicago court basement, where they would appear rapid-fire before a judge in the courtroom over video.

Defense lawyers called it a “cattle call” and said they had no avenue for direct, private communication with their clients. Defendants didn’t get the chance to point out mistakes in their criminal records, for instance, or to explain mitigating circumstances that could help their attorneys argue on their behalf for pretrial release. Probable cause was found and bail was set for each case in about 30 seconds. Attorneys argued that all of this impeded their clients’ rights to effective counsel and due process.

Northwestern University researchers studied the amount of money bail assigned to cases before and after the advent of video and found that the change from in-person hearings to video hearings coincided with a 51 percent increase in bail amounts, on average.

In 2006, a federal class action lawsuit against Cook County challenged the use of CCTV for bail hearings as unconstitutional. After the Northwestern researchers released the results of their bail analysis in 2008, the lawsuit became moot because the county voluntarily switched back to in-person bail hearings for felony cases.

Florida’s Dade County has continued to use CCTV for bail hearings for the past three decades, but the public defender’s office moved the attorneys from the courtroom to the jail several years ago. Attorneys are no longer in the same room as the judge, said the county’s public defender, Carlos Martinez, but they have the access to their clients that they need to do their jobs. (Since the pandemic, they are back in the courtroom again, speaking to their clients by phone.) In an ideal system, he added, the hearings would actually take place right in the jail, so that everyone is in the same place and video is rendered unnecessary.

The dehumanizing effect of video

Video hearings can also put defendants at a visual and auditory disadvantage, research shows. People seem less like people when seen through a screen, and this has an impact on outcomes. Studies have shown that people are more likely to be deported in immigration hearings if they appear on video than in person, and people applying for asylum are less likely to be granted it over video too.

Just as important as what people in court can see is what they hear. “The audio feature on some videoconferencing technology uses a middle bandwidth filter that cuts off low and high voice frequencies, which are typically used to transmit emotion,” reads a 2015 Justice Department–funded report about video hearings. “This feature removes critical emotional cues that can be used by judicial officers to determine a defendant’s remorse and character.”

“Whether you’re in front of a judge or in front of a jury, they’re judging credibility,” said Peter Kratsa, president of the Pennsylvania Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers, “and the way to judge credibility is to be in the room with somebody, not over camera.”

Access and accountability

Videoconferencing technology can be an equalizer. Public defenders can save money by not having to pay airfare for expert witnesses; attorneys and experts can appear in several courts in different jurisdictions on the same day. But there’s still a threshold to technology, below which someone isn’t on equal footing.

What if someone gets arrested, granted bail, assigned a first court date, and doesn’t have a computer to attend? He or she could get a bench warrant, and possibly get sent back to jail.

“There are homeless people who don’t have a computer; there are 5 or 10 percent of all people who don’t have a computer,” said Hal Shuhmacher, president of the Florida Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers. “I suppose it can be done, but I just foresee potential problems there.”

Of course, people can always call into video conferences with a regular telephone line, but not being able to see what’s going on puts them at a significant disadvantage, compared with others who have the full audiovisual experience.

The question of access extends not just to defendants and plaintiffs, but to their families, their friends, advocates, and the curious public. According to Jamiles Lartey, reporting in The Marshall Project, volunteer court monitors, who observe court proceedings to gather data on bail and other justice issues, say they aren’t getting access to video hearings since the pandemic began.

Privacy concerns

On the other hand, the balance between public and private in court is a delicate one—because there’s public, and then there’s public.

Bryce Covert pointed out in The Appeal last year a problematic aspect of the Broward County, Fla., bail hearings streaming live on the website of the local newspaper: “During the proceedings, judges have to make sure that pleas are offered voluntarily, which means they will often ask if a defendant has been diagnosed with a mental illness or are on any medications that would prevent knowingly offering a plea.”

In an open courtroom, anyone could potentially walk in at any time and watch. But is that the same as broadcasting live online across the world, or posting the recordings on YouTube for all time? How videos of hearings are saved and disseminated could complicate a lot of aspects of the process.

“It’s going to make the issue of jury selection harder, if everything’s available online and anybody can go watch,” said Martinez, the Dade County public defender. “And what happens with sealing and expungement? What if you seal and expunge your criminal record, but you still have all these videos available of all your court hearings?”

Looking to the future

Some courts have reacted to the pandemic by putting almost all operations on hold for now—and with it, defendants’ right to a speedy trial. There’s an enormous pressure for courts to start back up again, and the safest way to do that is either by video or phone. What technological substitutes courts allow vary from state to state and are changing every day. (The National Center of State Courts is keeping track here.)

As sudden as this transition is now, many attorneys said that the coronavirus crisis is merely the catalyst for speeding up changes that were inevitable anyway. Some court administrators are already saying they may never go back to doing everything in person because of how much time and money video saves.

But if it’s inevitable, attorneys say, they want it done right. Martinez said he hopes to see a type of video conferencing program that makes it easy for attorneys to have private side-conversations with their clients or the judge. And he wants to know how his attorneys can make their clients stop talking when they’re saying something they shouldn’t and leaning over to shoosh them isn’t an option. Right now, attorneys are just shouting over their clients into their computer mics.

“Maybe tech might have some of these answers,” said Martinez. “[It] isn’t there yet.”

This article was originally published on The Markup by Lauren Kirchnerand and was republished under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives license.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.