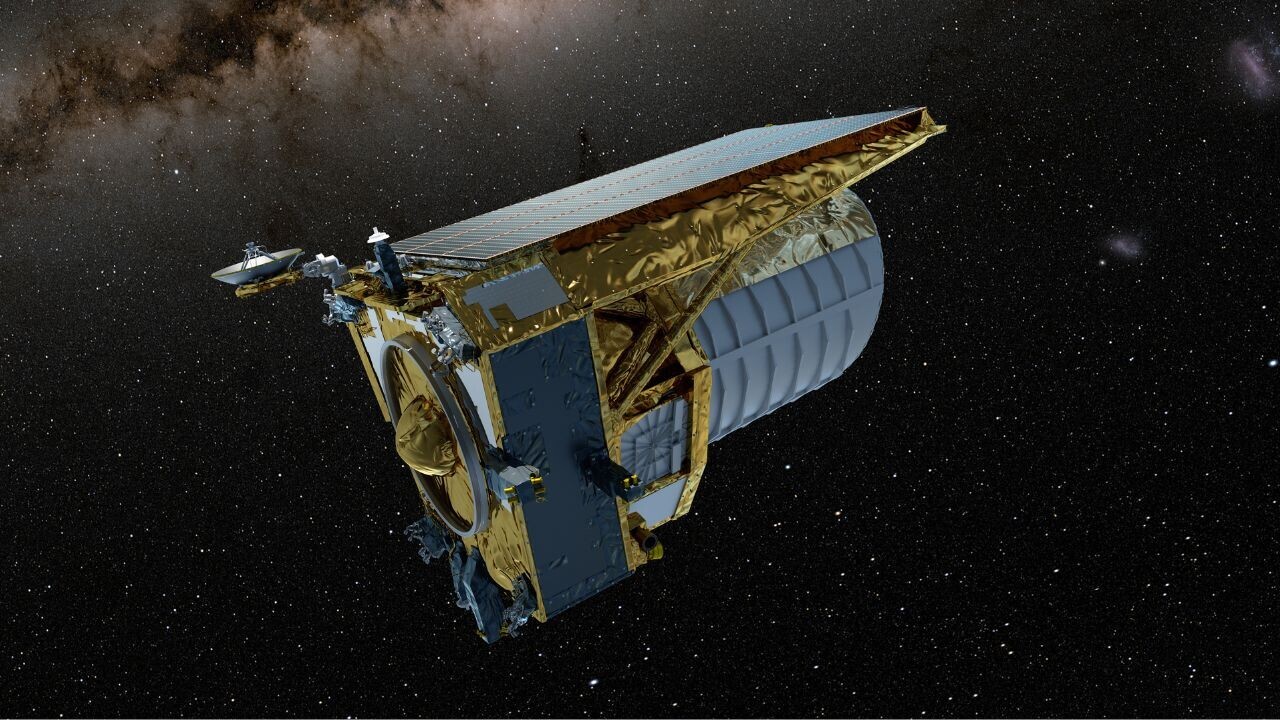

The European Space Agency has released the first major batch of data from its “dark universe” telescope Euclid. What’s inside could change our understanding of dark matter and the expansion of the universe.

The data comprises just one week’s worth of deep field images from three points in space. They make up just 0.4% of the vast area Euclid will capture, which scientists say will be the largest 3D map of the sky ever created.

With one scan of each region so far, Euclid has already spotted 26 million galaxies, each potentially containing millions of stars and billions of planets. The furthest of these galaxies are 10.5 billion light years away from Earth, meaning the images you see are almost as old as the universe itself.

The Euclid map of the stars

Hiding amongst all those millions of galaxies are rare phenomena called gravitational lenses or “Einstein rings,” named as such because they prove Albert Einstein’s prediction that gravity warps spacetime, causing light to bend as it travels through. Gravitational lensing occurs when a massive object, like a galaxy or black hole, bends the light from a galaxy behind it — forming visible distortions or arcs around the galaxy’s nucleus.

In this new batch of data, Euclid has more than doubled the number of gravitational lenses that have been captured from space. ESA estimates that Euclid will capture 100,000 strong gravitational lenses by the end of its six-year mission, around 100 times more than currently known.

Today’s data has also revealed an even rarer phenomenon: double gravitational lensing, also called double source plane lensing. This happens when light from two distant galaxies passes through the same galaxy, causing a double lensing effect.

Finding double gravitational lenses

Look at the image above and go to the fourth column, third from the bottom. The image is faint but you can make out two outer arcs and then two inner arcs close to the centre of the galaxy nucleus. That’s a double gravitational lens.

Double gravitational lensing could help scientists better understand dark energy and the expansion of the universe, because, in theory, an expanding universe will determine the angle of the arcs.

“Double-source plane lenses are extremely rare — only a few have ever been found,” said Euclid Consortium scientist Mike Walmsley at a press briefing. “But we think we’ve found four good candidates already from just a week’s worth of data covering a fraction of the night sky. We’re confident that Euclid will quickly capture enough of them to allow scientists to start measuring their effects.”

To find such rare phenomena hiding amidst Euclid’s images, the European Space Agency (ESA) enlisted the help of thousands of volunteers — and AI algorithms.

Euclid’s AI-powered galaxy finder

Launched in 2023, Euclid has observed about 14% of its total survey area so far. By the time its mission is complete, the telescope is expected to capture images of more than 1.5 billion galaxies, sending back around 100GB of data every day.

These images provide scientists with unprecedented opportunities — and huge problems when it comes to finding, categorising, and analysing all the objects within them.

To speed up the process, the Euclid consortium has developed an AI-powered galaxy spotter — called “Zoobot.” The algorithm was trained on decades’ worth of citizen science work, from volunteers who scan through images and identify each object.

From today’s data drop, Zoobot put together a detailed catalogue of 360,000 galaxies. Thousands of volunteers from the Space Warps citizen science project then sorted through the most promising candidates. That’s how the gravitational lenses were identified.

“We’re at a pivotal moment in terms of how we tackle large-scale surveys in astronomy. AI is a fundamental and necessary part of our process in order to fully exploit Euclid’s vast dataset,” said Walmsley, who has worked on astronomical deep learning algorithms for the last decade.

The dark universe explorer

Euclid launched on a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket from Cape Canaveral in Florida on 1 July, 2023. It returned its first images in August of that year, and in May last year released its first scientific data.

Euclid’s mission is to shed light on two of the universe’s most perplexing mysteries: dark energy and dark matter —, thought to make up 95% of the cosmos. Scientists theorise that dark energy is responsible for accelerating the universe’s expansion and that dark matter acts as cosmic glue that holds the galaxies together. Yet the nature of these components is still unknown.

To build its 3D map of the night sky, the telescope is deploying two high-tech cameras: VIS, which captures the cosmos in visible light, and NISP, which measures the distances to galaxies and the expansion speed of the universe.

Euclid is set to provide us with an unprecedented chronology of the history of the cosmos and help us unravel the mysteries of the universe – and our own existence.

The three deep field previews can now be explored in the ESASky app. Euclid Deep Field South here, Euclid Deep Field Fornax here, Euclid Deep Field North here.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.