Ceres is rich with water, the Dawn spacecraft finds. What can this mean for finding life on other worlds?

Ceres is the largest dwarf planet in the inner solar system, and new findings from the Dawn spacecraft reveal this body is covered in salty oceans.

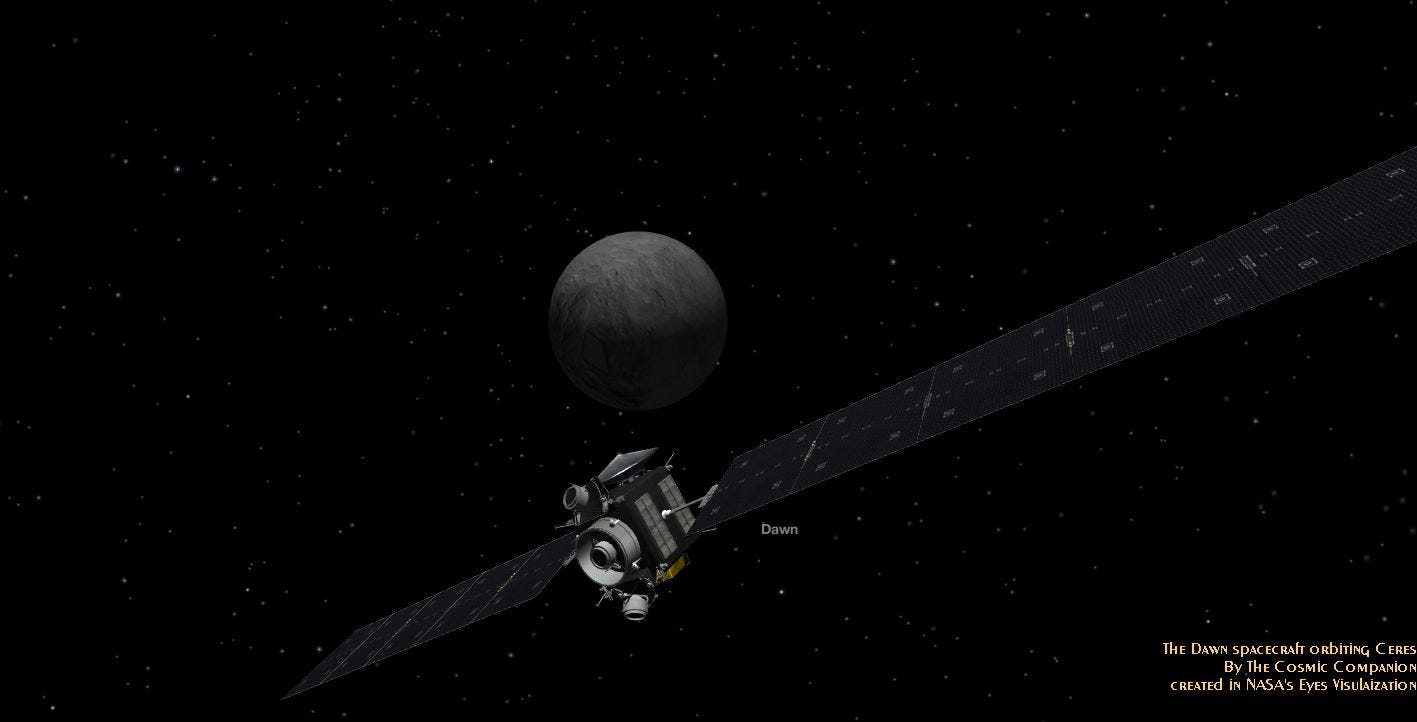

Data from the Dawn spacecraft, the first robotic explorer to orbit a dwarf planet, revealed this icy body was surprisingly active, housing an ocean far deeper than any found on Earth.

Are you Ceresius?

First seen on January 1, 1801, Ceres was tracked for 41 days by an Italian monk named Giuseppe Piazzi, before he fell ill. Just at this time, Ceres moved into the halo of the Sun, leaving other astronomers without the ability to confirm the discovery.

[Read: Jupiter’s atmosphere is regulated by ammonia storms, research reveals]

The famed astronomer Johannes Kepler had earlier predicted that a planet should orbit in between Mars and Jupiter. When first seen by Piazzi, Ceres was thought to be that predicted planet.

With less than six weeks of observations and Kepler’s equations, the mathematics of the early 19th Century was unable to accurately predict the position of the newly-discovered body, making finding that world once more exceptionally challenging.

Ceres was eventually re-discovered, but it was not long classified as a planet. In 1802, just a year after its discovery, additional bodies were found in orbit between Mars and Jupiter, and the term asteroid was coined to describe these minor bodies.

Named in honor of the Roman Goddess of corn and harvests from who we derive the word cereal, Ceres contains one-quarter of all the mass of the main asteroid belt. Still, at just 476 km (296 miles) in diameter, this minuscule world is still 14 times smaller than Pluto.

Re-classified as a dwarf planet in 2006 due to its unique structure, Ceres rotates around its own axis once every nine hours, as it revolves around the Sun every 4.6 years.

Facula faculae… facula faculae…

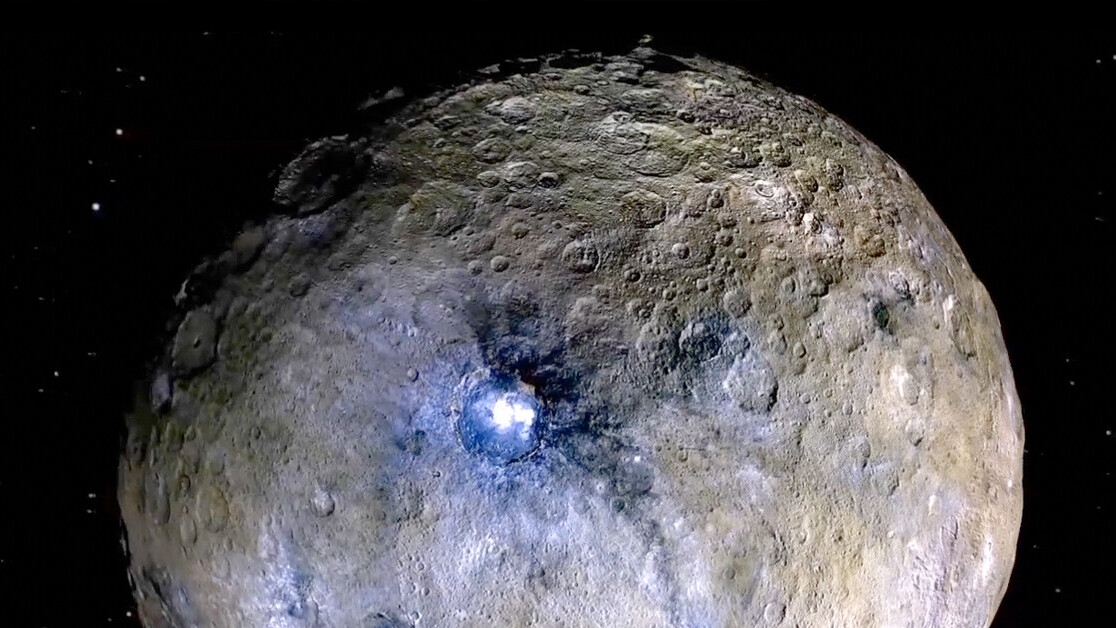

When Dawn arrived in 2015, Ceres became the first dwarf planet to be visited by a spacecraft. As it approached, Dawn discovered two bright white areas, named Cerealia Facula and Vinalia Faculae.

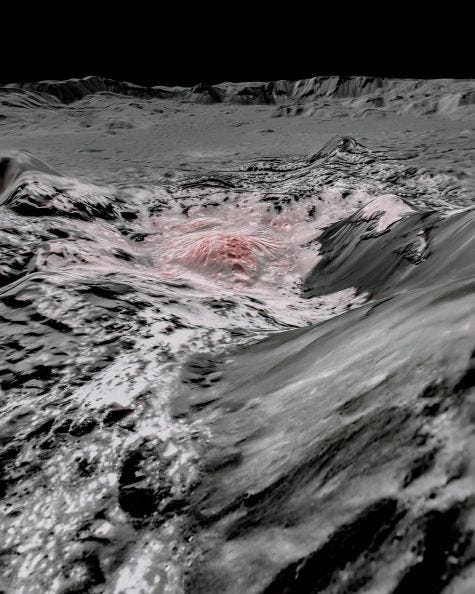

In addition to these regions, Occator Crater on Ceres was found to be home to conical hills, similar to small mountains of ice called pingos found in Arctic regions of Earth. Similar structures have also been spotted on Mars, but this recent finding marks the first time they have been seen on a dwarf planet.

Researchers found the density of Ceres becomes greater toward its center, suggesting salt and mud are settling into the center of this diminutive world.

By the time Dawn ended its mission in October 2018, the observatory had seen Ceres from heights as low as 35 kilometers (22 miles) above the surface. These images revealed details never before seen in the distinctive shiny patches found on the dwarf planet.

“Scientists had figured out that the bright areas were deposits made mostly of sodium carbonate — a compound of sodium, carbon, and oxygen. They likely came from a liquid that percolated up to the surface and evaporated, leaving behind a highly reflective salt crust. But what they hadn’t yet determined was where that liquid came from,” NASA officials describe.

While some icy moons in our solar system take advantage of tidal heating caused when they orbit large planets, Ceres is devoid of any such warmth. Still, these watery deposits resemble, in several ways, water moons throughout the solar system.

A salty rock story

Micrometeorites continually falling on the surface of Ceres should darken salt deposits, suggesting these white regions are geologically young. This finding drove engineers to utilize Dawn to uncover the mysteries of the bright patches.

Analysis revealed these patches are less than two million years old. Chemistry in the region was found to include salt molecules bounding to water and ammonium chloride, a salt.

Dawn found evidence of liquid water reaching the surface in these regions, adding to the evidence for liquid oceans beneath the surface of Ceres.

“The scientists found two main pathways that allow liquids to reach the surface. For the large deposit at Cerealia Facula, the bulk of the salts were supplied from a slushy area just beneath the surface that was melted by the heat of the impact that formed the crater about 20 million years ago. The impact heat subsided after a few million years; however, the impact also created large fractures that could reach the deep, long-lived reservoir, allowing the brine to continue percolating to the surface,” Dawn Principal Investigator Carol Raymond stated.

Powered by ion engines, Dawn was the first spacecraft to orbit two main targets — the giant asteroid Vesta and Ceres. When the robotic explorer ran low on hydrazine fuel needed to maintain orientation and generate power, engineers sent the vehicle into a high orbit, preventing the vehicle from impacting on Ceres for several decades.

If water can remain as a liquid on Ceres, it may be possible for water to remain liquid on other dwarf planets, researchers suggest. With the discovery of lifeforms pushing the limits of life on Earth, chances become ever greater that we will soon find evidence for life on other worlds.

This article was originally published on The Cosmic Companion by James Maynard, founder and publisher of The Cosmic Companion. He is a New England native turned desert rat in Tucson, where he lives with his lovely wife, Nicole, and Max the Cat. You can read this original piece here.

Astronomy News with The Cosmic Companion is also available as a weekly podcast, carried on all major podcast providers. Tune in every Tuesday for updates on the latest astronomy news, and interviews with astronomers and other researchers working to uncover the nature of the Universe.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.