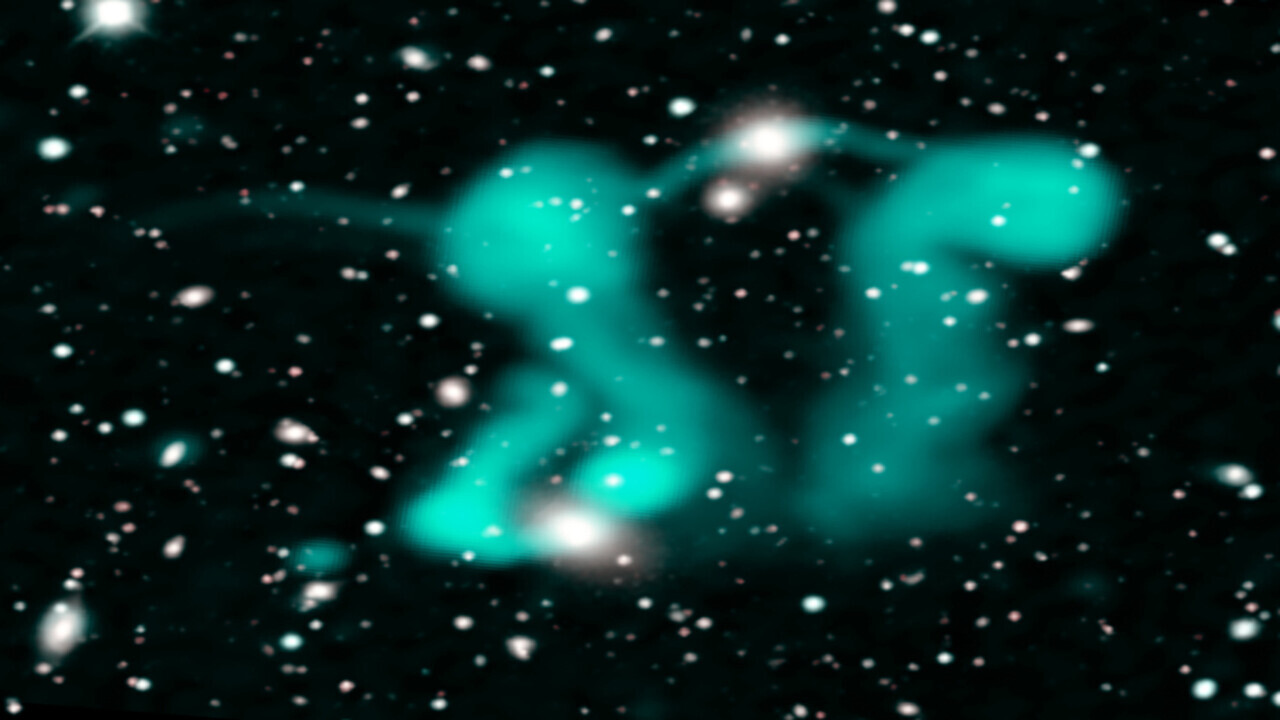

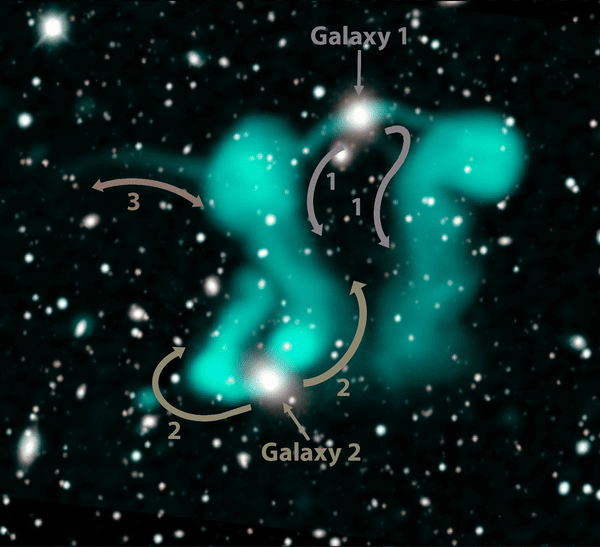

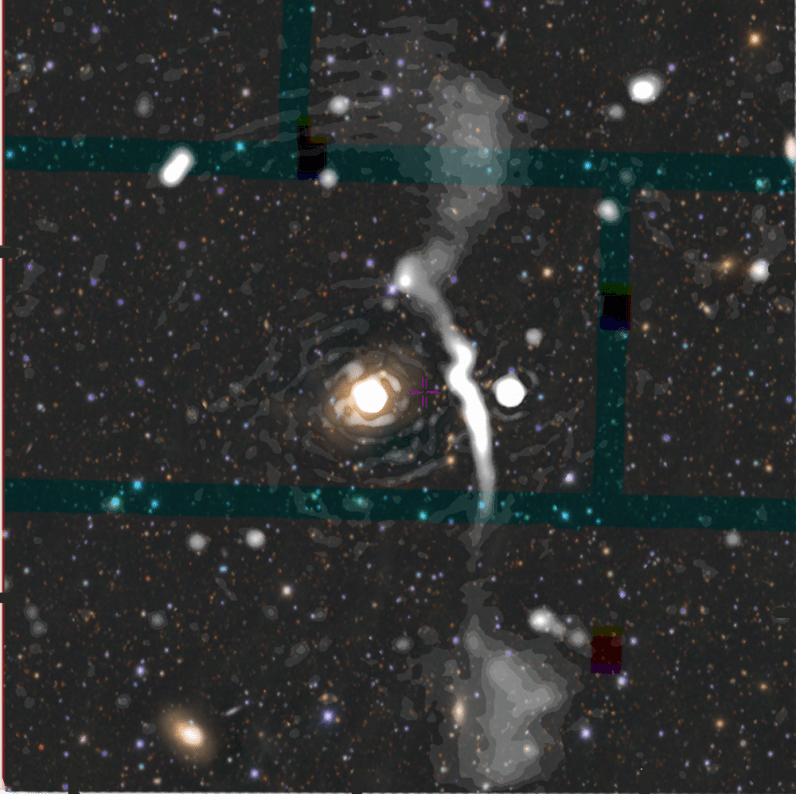

Scanning through data fresh off the telescope, we saw two ghosts dancing deep in the cosmos. We had never seen anything like it before, and we had no idea what they were.

Several weeks later, we had figured out we were seeing two radio galaxies, about a billion light years away. In the center of each one is a supermassive black hole, squirting out jets of electrons that are bent into grotesque shapes by an intergalactic wind.

But where does the intergalactic wind come from? Why is it so tangled? And what is causing the streams of radio emission? We still don’t understand the details of what is going on here, and it will probably take many more observations and modeling before we do.

We are getting used to surprises as we scan the skies in the Evolutionary Map of the Universe (EMU) project, using CSIRO’s new Australian Square Kilometer Array Pathfinder (ASKAP), a radio telescope that probes deeper into the Universe than any other. When you boldly go where no telescope has gone before, you are likely to make new discoveries.

A deep search returns many surprises

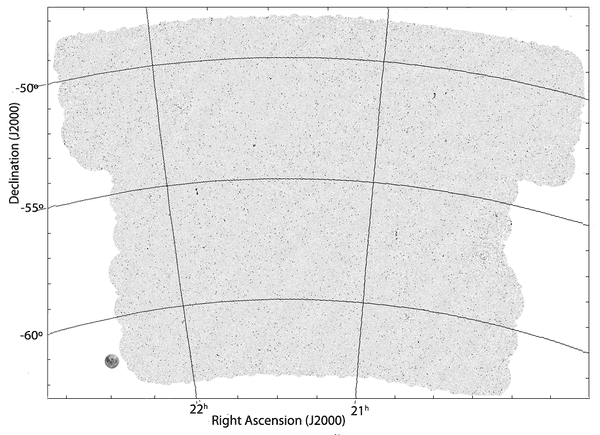

The Dancing Ghosts were just one of several surprises found in our first deep search of the sky using ASKAP. This search, called the EMU Pilot Survey, is described in detail in a paper soon to appear in the Publications of the Astronomical Society of Australia.

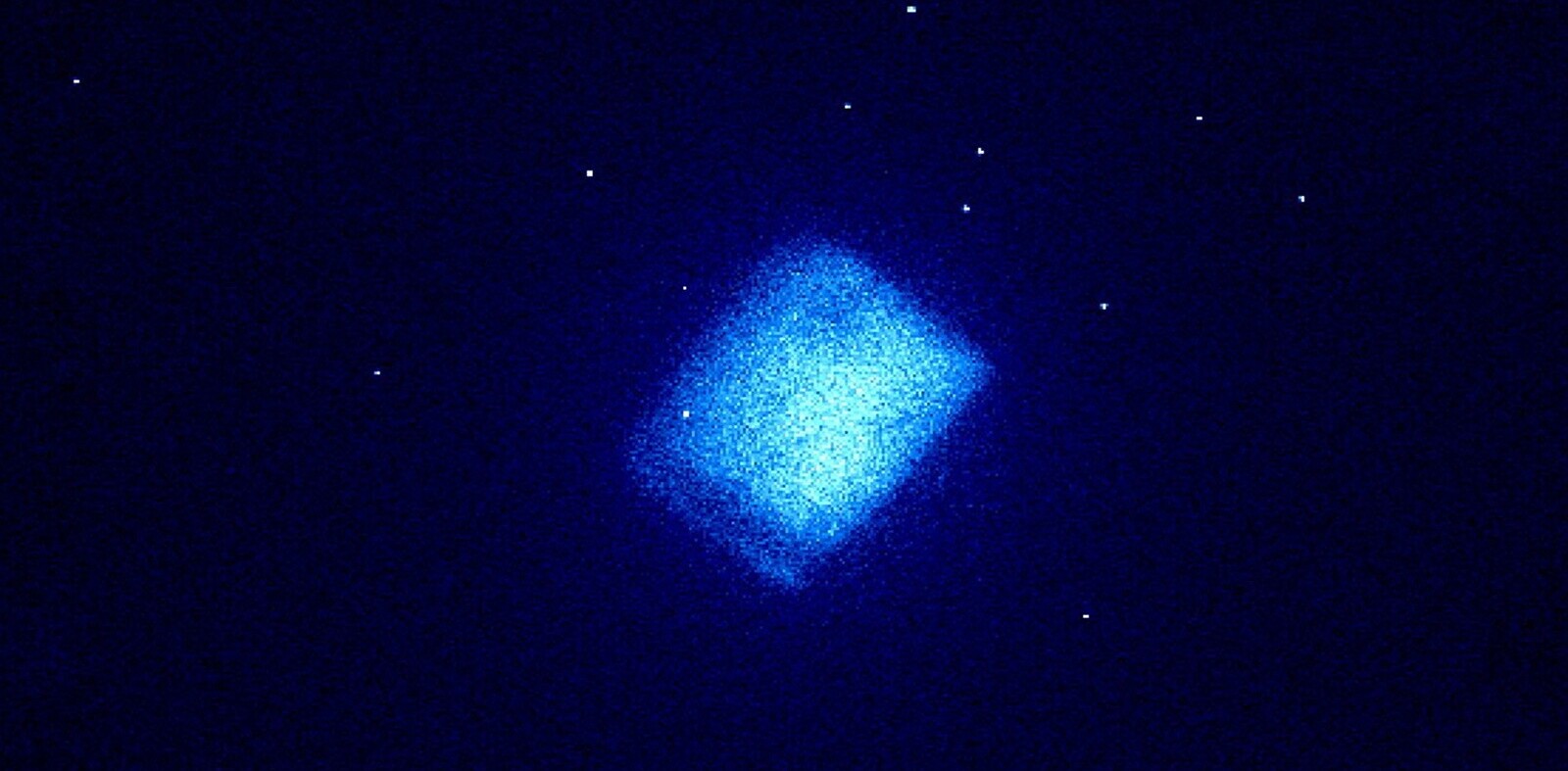

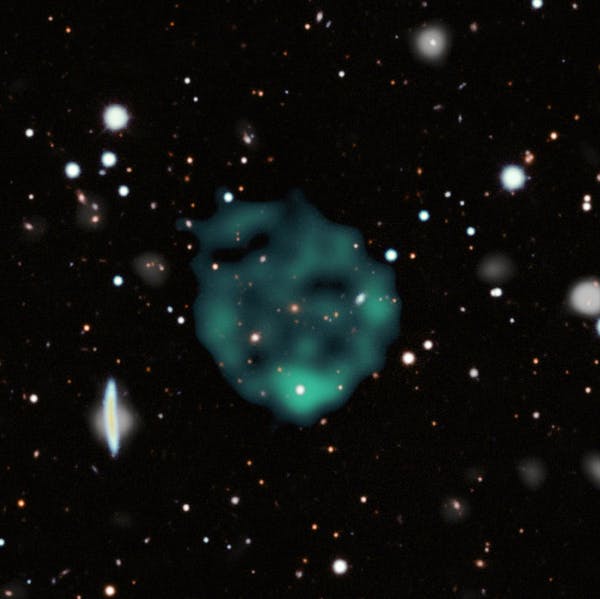

The first big surprise from the EMU Pilot Survey was the discovery of mysterious Odd Radio Circle (ORCs), which seem to be giant rings of radio emission, nearly a million light years across, surrounding distant galaxies.

These had never been seen before because they are so rare and faint. We still don’t know what they are, but we are working furiously to find out.

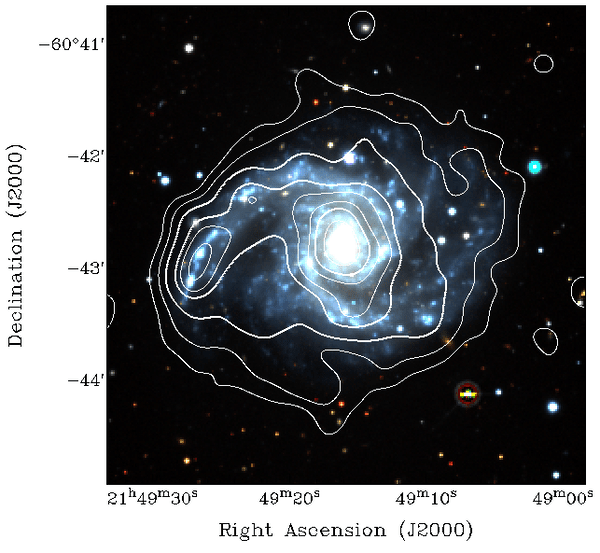

We are finding surprises even in places we thought we understood. Next door to the well-studied galaxy IC5063, we found a giant radio galaxy, one of the largest known, whose existence had never even been suspected.

This new galaxy also contains a supermassive black hole, squirting out jets of electrons nearly 5 million light years long. ASKAP is the only telescope in the world that can see the total extent of this faint emission.

What EMU can do

Most known sources of radio emissions are caused by supermassive black holes in quasars and active galaxies, which produce exceptionally bright signals. This is because radio telescopes have always struggled to see the much fainter radio emission from normal spiral galaxies like our own Milky Way.

The EMU project goes deep enough to see them too. EMU sees almost all the spiral galaxies in the nearby Universe that were previously seen only by optical and infrared telescopes.

EMU can even trace the spiral arms in the nearest ones. EMU will help us understand the birth of new stars in these galaxies.

These some of the first results the EMU project, which we started in 2009. The EMU team of more than 400 scientists in more than 20 countries has spent the past 12 years planning the project, developing techniques, writing software, and working with the CSIRO engineers who were building the telescope. It has been a long haul, but we are at last seeing the amazing data we have dreamed of for so long.

But this is only the start. Over the next few years, EMU will use the ASKAP telescope to explore even deeper in the Universe, building on these discoveries and finding more. All the data from EMU will eventually be placed in the public domain, so that astronomers from around the world can mine the data and make new discoveries.

But don’t take my word for it. You can already use EMU Pilot Survey data to explore the radio sky yourself, using the zoomable image on our website.

Use your mouse wheel to zoom in from the big picture down to the finest details, and see what you find. Perhaps you may even discover something there that the astronomers have missed.![]()

Article by Ray Norris, Professor, School of Science, Western Sydney University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.