Let me start this post off by saying that impostor syndrome has already been covered profusely and at length, and there’s probably nothing new I can add to the discussion, so let me stop here, thanks for reading, and sorry for wasting your time.

Ahem. While there’s already tons of advice for overcoming impostor syndrome, I find it usually falls into one of two buckets:

- YOU! An impostor?! No way! Just stop thinking that!

- Fake it ‘til you make it. If you just keep acting confident, one day you will be.

The first angle is clearly useless, and the second, I’d argue, is neither possible nor advisable.

Hot take: you cannot successfully fake being confident. Not to say it wouldn’t be useful if you could. Research shows that when it comes to appearing competent, confidence is as (or more) persuasive than actual competence in getting people to think you know what you’re doing. Overconfidence can get you far in life. But the same studies show that it’s not enough to merely fake being confident. You have to actually believe it–you have to be “honestly overconfident.” In a fantastic piece for The Atlantic, Katty Kay and Claire Shipman write of their interview with the confidence researcher Cameron Anderson:

True overconfidence is not mere bluster. Anderson thinks the reason extremely confident people don’t alienate others is that they aren’t faking it. They genuinely believe they are good, and that self-belief is what comes across. Fake confidence, he told us, just doesn’t work in the same way. […] Most people can spot fake confidence from a mile away.

“Most people can spot fake confidence from a mile away.” It’s a result that’s borne out in the lab, and one I’ve validated in my own life tons of times.

If you write software for a living, then you likely spend your days interacting with people who argue with such monomaniacal vigor about optimal keyboard shortcuts you’d think they were defending their PhD theses. On top of that, if you are a woman, you probably also spend lots of time convincing people you really do know how to code. Combine these two and the fact that programming is actually hard and it’s no wonder so many of us feel like impostors. I first learned the name for this feeling in 2013, when I was a sophomore college and got my hands on Facebook COO Sheryl Sandberg’s new book, Lean In. Thanks to that book, I (and so many others) started asking myself, “Is the problem that I’m an impostor, or that I have impostor syndrome?”

It would be hard for me to name a single female software engineer who doesn’t wonder this on the regular (surely many men do, too–but I find it’s rarer). But this is where things get complicated, because when you know you may be suffering from impostor syndrome, you feel the need to counteract it. You come to the conclusion that the queasy feeling in your gut is wrong–that the insecure part of you is delusional–and that you should no longer let your gut instinct guide your actions. Instead, you enable manual override, behaving in the way you think a confident person would. You start conversations by listing your credentials; you find every opportunity to name drop your alma mater; you post your every accolade on social media. (I’m guilty of all of these things.) It feels like bragging, but it’s hard to tell, because isn’t that what somebody with impostor syndrome would think?

But my take is that this sort of self-promotion rings hollow. Meanwhile, in the midst of our credential-dropping, we often fail to show confidence in situations that actually do sway people’s views of us. For example, I have a tendency to give an opinion and immediately caveat it with, “but I have no idea what I’m talking about,” and, “but you should definitely Google that.” And this type of back-talk absolutely does make me appear less competent.

In other words, when we force ourselves to ignore the “delusion” that is impostor syndrome, we end up behaving in ways that don’t feel very human–and don’t come off as genuine to other humans. Meanwhile, we fail to address the root of the problem.

So what’s the solution? For me, the answer has been to focus on acquiring “true confidence”–the type that my brain and my gut both agree I should have. I’ve done this neither by repeating to myself the daily affirmation “You are great at Python developer,” nor by going back to school for my PhD. But here’s what’s worked for me.

Calibrate yourself

There’s a famous Bob Thaves quote that says, of the dancer Fred Astaire:

Sure he was great, but don’t forget that Ginger Rogers did everything he did, backwards, and in high heels.

It may well be true that no matter how qualified you are, if you don’t come in the right package–if you’re not tall or male or confident or charismatic–that you have to work twice as hard for people to realize it. If they ever realize it.

But most of us don’t go from having two left feet to being Ginger Rogers overnight. We start our careers knowing nothing, struggle through the early years as newbies, and eventually learn enough to call ourselves experts. Yet we rarely know at any moment where we fall on that spectrum (besides, expertise is relative, isn’t it?).

Which says to me that all of us must secretly be thinking: “Some people who think they’re impostors actually are! How can I be sure I’m not one of them?”

So my first piece of advice is to try, if you can, to answer this question in some sort of objective way: how competent am I compared to my peers? This isn’t the type of question that’ll make it into the pages of any wellness-minded self-help book, but for me it’s been incredibly helpful (and not because I’m some amazing 10x programmer).

The analytics-crazed field of software development has tools for doing just this. One engineering manager I knew kept a dashboard that analyzed the code commits of all his team members and computed their relative productivity (I’m sure glad he wasn’t my manager). I’m not suggesting you use this Orwellian gauge as a measure of your self-worth, but if you have at least some way of objectively measuring your standing, you can better identify whether your insecurity comes from imagined or real performance differences. And this, particularly in the world of tech, is important, because non-objective measures abound.

You don’t need a college degree in Computer Science to be a successful coder, but taking the traditional university route did give me one irreplaceable perspective: seeing first hand the differences in the way I think about myself, versus the way my classmates–who would eventually become my coworkers–thought and talked about themselves.

Switching into Computer Science as a sophomore, I was already “behind.” Lots of my classmates had been coding since they were in utero. The field is vast, and I had no idea what people were talking about most of the time: Arch Linux? Lambda functions? emacs? Neural networks? And it wasn’t just the lingo that intimidated me. It was also that my classmates had such strong opinions! Why was it so important that I give up my Macbook Pro for a computer with an operating system that couldn’t hibernate or play audio? Why did I have to write code in a text editor with no graphical user interface that was built in the 70s? I had no idea, but I was convinced it was what legit programmers did.

“The thing you don’t realize,” my friend Raymond, a precocious coder two years above me, said, “is that they spend all this time arguing about things they don’t know anything about.” It took me three years of CS education to realize that so many of my classmates were, indeed, casually spewing bullshit, and there really wasn’t any good reason to write code in emacs. (#vim4life)

It’s often easier to become close friends with the classmates you’re pulling the same punishing all-nighters with than it is with your co-workers. And because of that, I saw this pattern play out time and again: a friend speaks at length and with authority about quantum computing, but on further interrogation reveals their entire background knowledge boils down to four Tweets. Their standards for how much they had to know about a topic in order to argue about it were much lower than mine. Which gave me the impression that was a lot further “behind” than I actually was.

The plural of anecdote is not data, but the data do support this “confidence gap” across gender lines six ways to Sunday: in the lab, women thought their performance on tests were worse than men did, even when their scores were the same. In one study, women applied for promotions only when they thought they met 100 percent of job qualifications; men applied when they met just 60. This phenomenon is one of the most repeatable results in psychology.

I’ll always remember applying for internships junior year when my then-boyfriend came to me distraught that he’d been rejected for a role as an Android developer.

“But Frank*,” I said, “you don’t know anything about Android development.”

To which he replied:

“And without this job, how will I ever learn?”

I’ve seen another common variant when my female coworkers are asked if they can complete a task. In one meeting, a project manager asked (the only other) female engineer on our team if she could build out a feature.

“Maybe? I don’t know… I’ve never worked on anything like that. I’ll have to ask my manager about it.”

I’ve never in my life heard a male coworker say anything like that. It’s not that my male coworkers claimed they could do everything. It’s just that they usually placed the blame elsewhere–on complicated software or incompetent coworkers–rather than on themselves. But more often, they’d just say yes, assuming that whatever they didn’t know they’d be able to learn on the job.

Unfortunately, I can’t give you an exact formula for learning how you stack up, but I will say the most useful “calibration exercise” I’ve ever done was becoming an interviewer. In my first job at OkCupid, I routinely reviewed resumes from applicants who listed such achievements as “trained and deployed neural networks at scale” or “built a compiler from scratch” but that, when fingers hit keyboards, couldn’t write a for loop to save their lives.

In other words, if you let your opinions of others be swayed by those who can talk the talk, it’s easy to feel that you’re further behind than you really are. In this way, finding a more concrete measure–whether its lines of code committed, performance reviews, or a candid conversation with your manager–can be useful. Maybe no one measure is perfect, but together they can paint a clearer picture.

Of course, at the end of this calibration exercise, you may learn something that you don’t like. Maybe that means you do need to spend time garnering experience or studying hard to level up your skills. No shame there. It’s an actionable insight. And, if you discover that you really are bad at something, despite hard work, that’s okay, too. I’ve never been happy in a job I didn’t feel that I was good at. But I have stayed in those roles longer than I should have because I spent so much time thinking I just had impostor syndrome. The right move for me has always been to pivot to something that suits my strengths better. Or, of course, you could simply say fuck the competition–you like the job you do and that’s all that matters.

Talk the talk

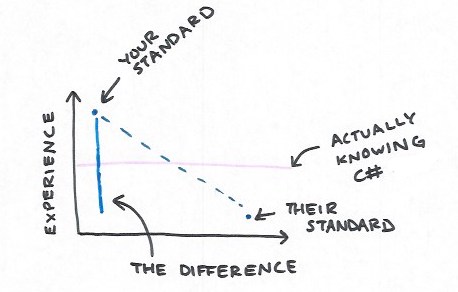

It’s important to calibrate your abilities against your peers not just so you know how “good” you are, but also so that you understand how your peers (who are sometimes your competition) are representing themselves. No, you don’t want to lie on your resume and say you’re C# expert when all you’ve written is “Hello, world.” But at the same time, if everyone on the job market is listing themselves as experienced C# developers with only a year of experience, shouldn’t you be using that as the same bar for yourself? In fact, if you don’t do this–if you hold yourself to a higher bar–you might be inadvertently misleading folks into thinking you’re less competent than you really are, because you’re using a different scale.

Overselling your abilities is unwise and feels “icky.” But when you really understand how people with your abilities represent themselves, you may find you speak with more confidence naturally, simply because you feel it’s honestly deserved.

And on the topic of talking the talk, here’s another tip: don’t unnecessarily undercut yourself. As stated, I would never advise someone to try to sound like they’re more knowledgeable than they are. But that doesn’t mean you should go out of your way to kill your credibility.

I’m guilty, often, of being so afraid of being “found out” that when I say something like,

“I have 8 years of experience with Python,”

I also tack on:

“But I don’t know anything about Flask or Django or how to author a pip package, and I don’t know the difference between Python 3 and Python 2, and I’ve never used the collections package, and sometimes when I laugh too hard, I pee myself a little bit.”

My fiancé once asked his dad for advice on asking out a girl who was “out of his league.” His father replied:

“Let her figure that out.”

For me and many of the women I’ve spoken to, we are so afraid of saying something that turns out to be wrong that we’re willing to massacre our credibility right up front to avoid that possibility. This is unnecessary. If you say something wrong, someone will look it up and correct you, or maybe they won’t. Big whoop. Just don’t try this on Twitter.

You’re smart even if you don’t know about Kubernetes

Maybe this is the most important tip of all.

For most of this post, I’ve suggested actions you can take to feel like less of an impostor – to change the way you think of yourself, and the way you present yourself to others. But of course, there’s a lot about the way people perceive you you simply cannot control, especially when bias is involved. As a woman in tech, I will always struggle to convince folks I’m competent, and their reactions will always make me feel less so. Plus, sexism aside, tech is filled with lots of jerks, and many more people who aren’t jerks, but that occasionally speak like them. I don’t know how to change that.

But I do think there’s value in recognizing when you’re talking to a jerk, so you don’t internalize this as a flaw in yourself. You cannot reasonably go up to Vint Cerf, the inverter of TCP/IP, and expect to have a debate about network protocols in which you don’t get totally schooled. But no matter how much or how little you know about a subject, you always deserve to be spoken to like a smart person. When I wonder if a coworker is talking down to me, I ask myself, “is this how that person would speak to me if I were Richard Feynman?” Because Richard Feynman doesn’t know about Kubernetes, but you’d never explain something to him like he were a hapless dummy.

Of course, when you identify you’re being talked down to, there’s not necessarily much you can do about it. But sometimes identifying the things you can’t change gives you more time to focus on the things you can.

But what do I know?

A very big thanks to Sara Robinson and Anu Srivastava, two of my wicked smart and thoughtful coworkers, for feedback on this post.

* “Frank,” you know who you are.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.